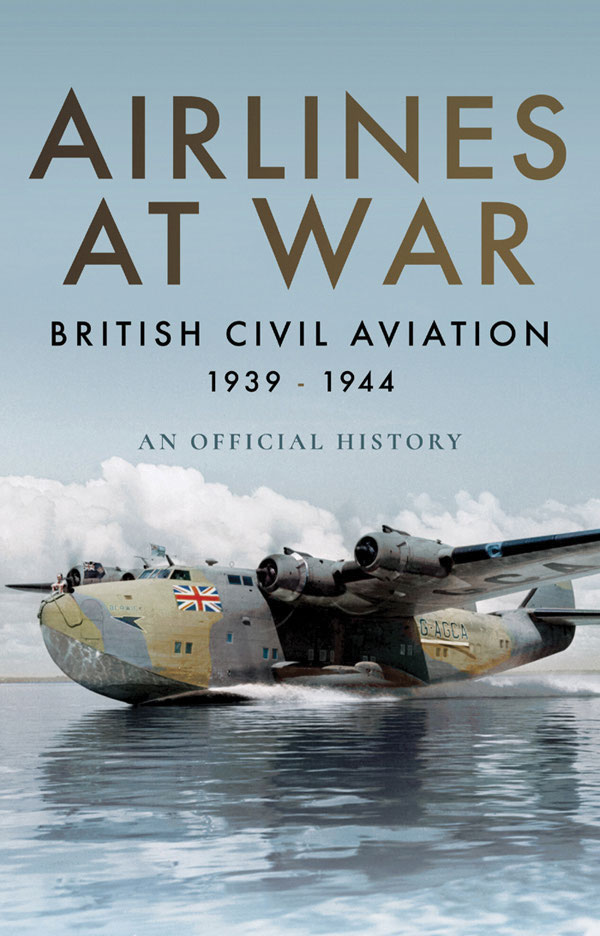

AIRLINES AT WAR

BRITISH CIVIL AVIATION 1939 - 1944

AIRLINES AT WAR

BRITISH CIVIL AVIATION 1939 - 1944

AN OFFICIAL HISTORY

AIRLINES AT WAR

British Civil Aviation 1939 - 1944

This edition published in 2018 by Air World Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

First published as Merchant Airmen: The Air Ministry Account of British Civil Aviation, 1939-1944, by HMSO, London, 1946.

Text alterations and additions Copyright Air World Books, 2018

ISBN: 978-1-47389-409-9

eISBN: 978-1-47389-411-2

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-47389-410-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For more information on our books, please visit

www.pen-and-sword.co.uk, email enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

or write to us at the above address.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

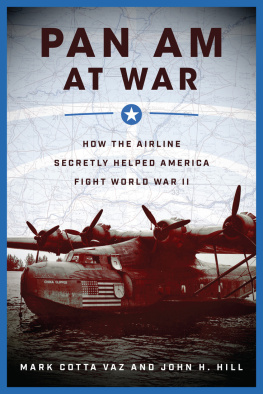

AT 13.15 HOURS Greenwich Mean Time on September 13th, 1940, the Empire flying-boat Clare, Captain J.T. Kirton, of British Overseas Airways Corporation, took off from the waters of Poole harbour in Dorset and set course westwards towards the Atlantic.

She trailed behind her, across the smooth harbour waters facing the haphazard little huddle of buildings on the quay, a widening wake of troubled white foam. She left behind her a still more troubled sky. The weightiest formations of the Luftwaffe were ranging over southern England, thrusting at the people of London in the longest daylight raids they had yet endured.

By mid-afternoon Clare had alighted on the waters of the Shannon at Foynes, in Eire, where there was no war save in the anxious minds of the people. The captain had hoped to continue his flight that evening, but when he consulted the meteorological information he was compelled to postpone his departure.

All next day the flying-boat lay on the Shannon, her crew turning to the radio for news of the mounting Battle of Britain. While they waited, another Empire flying-boat arrived from Poole, bringing with her a bundle of London newspapers which was stowed aboard Clare. The following day, September 15th, the tighter squadrons of the Royal Air Force were compelling the Luftwaffe to the tremendous climax of their daylight assault; 185 German aircraft were to be shot down before sunset. Before all that total had been reached, Clare had left her moorings on the Shannon, and at 18.10 hours G.M.T. she took off for Newfoundland. When the 185th German aircraft fell from the sky, Clare was already moving steadily through the mists and cloud over the Atlantic, flying on the Great Circle route to Newfoundland.

The two pilots, Captain Kirton and Captain J.S. Shakespeare, and the navigator, Captain T.H. Farnsworth, kept watch on the flight-deck throughout the night, navigating by the stars when they could see them through the clouds and by dead reckoning when they could not. Of the ocean beneath them they could see nothing, frequently nothing of the sky above; their world was contained for that night in the warmly lit flight-deck of the flying-boat, their thoughts on the mechanics of flight and the continual problem of navigation. Though even those necessities, one of them said, could not shut out altogether from their minds troubled speculation on the outcome of the air war which lay behind them, or remembrances of the growing number of their friends who had gone into the R.A.F. and who were losing their lives.

Their own immediate task, of course, predominated. Through the windows they could see nothing but a drift of darkness in which hung the firm, steady outline of the wing structure upon which they sometimes shone a feeble torchlight, seeking traces of ice formation by which, as it happened, they were not troubled. In the young daylight of September 16th, they sighted the Newfoundland coast with its hinterland of desolation sprinkled with many rivers and lakes.

Soon after they had crossed the coast they received a radio message to say that Botwood, their destination, was covered in thick local fog, with the cloud base at only 150 feet and visibility of less than 200 yards. Here was anxiety. Botwood lies on the shores of the saltwater Bay of Exploits, behind which rise hills to a height of several hundred feet; the amount of petrol remaining in the tanks after an Atlantic crossing did not encourage delay.

At 11.40 hours G.M.T., circling over Botwood, the crew saw that the only piece of cloud in the whole sky lay directly over Botwood itself and their alighting area. They circled for 20 minutes, cautiously descending. At last a gap appeared in the cloud, and through this gap they alighted on the Bay of Exploits.

They remained there for little more than an hour before taking off again for the United States. There was another brief halt at Boucherville near Montreal; then at dusk they were circling at a height of 1,000 feet, less than that of the topmost buildings, round the sky-line of New York. No matter how troubled the world, nobody can contemplate, after an Atlantic flight, anything other than the fascination of New York from the air. These merchant airmen commented to each other, as they always did on such an occasion, on this remarkable instance of the way in which nature anticipates man. They had all flown for years on the great Empire air-routes and were well acquainted with that most curious and massive rock-formation on the Baluchistan coast, just east of Jiwani, which thrusts up pinnacles in a striking imitation of the New York skyline.

On this occasion, the metropolitan spectacle was more beautiful than usual. As Clare made a circuit over the East River, as far as Queensborough Bridge, the lights of New York were just beginning to glitter through the dusk. We could see the dark pinnacles of skyscrapers in which batches of light would suddenly twinkle, one after the other, one of the captains described it. The lights twinkled and spread all over the city, until the whole thing reminded me strongly of a heaving mass of molten brass in a foundry. Have you ever seen it? A great city lighting up at dusk is just like that; for molten brass, just as it starts to cool, twinkles all over with lights.

But when we had alighted at La Guardia airport, moored up and gone ashore, we were all, I think, a little silent. It was impossible to escape the contrast between the two ends of our Atlantic flight. We had left behind the pitch-black cities of Britain, lit only by searchlights, bomb-flashes and fires, but full of people confident of victory; we had arrived at a city sparkling with light, where, as it seemed to us, the number of people who had any hopes in Britains survival, though increasing, was still very small. We met the warmest admiration for Britains stubbornness, but little feeling that it was any more than stubbornness, or that the fight would not soon be ended. Though the news of the great air victory of September 15th, so amazing that many could scarcely believe it, was flooding the city with a faint, new hope.