My humble thanks go to a number of people who have provided assistance during the writing of this book. At the Joint Services Command and Staff College, Squadron Leader Hedley Myers and Squadron Leader Graham OConnor were naturally supportive of my interest in a range of aviation subjects, as was Dr David Hall. During a research trip in the summer of 2015 the staff of the JSCSC library were as excellent as ever, and the staff of The National Archives, Kew, once again proved their worth and patience in dealing with numerous requests for large, dusty Air Ministry files. Thanks must also go to Melanie Thomas and Dave Bostock for helping me out during my Research trip to Kew. My former publisher John Lee must be applauded for the shared vision to get this pocket book series off the ground. At Bloomsbury Lisa Thomas has displayed much patience and her colleague Penny Phillips has proved an enthusiastically excellent editor. The advice and knowledge of Charlotte have once again provided a useful and different perspective upon vexed issues, while Harry and Lysander just love listening to Ron Goodmans thrilling score from 633 Squadron. Long may it continue!

Martin Robson, Ide, November 2015

Contents

The Mosquito represents all that is finest in aeronautical design

Wing Commander John de Lacy Wooldridge, Commanding Officer, 105 Squadron

It had awesome power on the leash in those huge engines and was eager on its undercarriage like a sprinter on the starting blocks who couldnt wait to leap up and away.

Sergeant Mike Carreck

The image of the de Havilland Mosquito held by many of my generation is of a derring-do assault on a German V-2 rocket fuel plant in Norway conducted by the brave pilots of the RAFs 633 Squadron. The stirring theme tune combined with whizzo (for their time) special effects was quite astounding to a small boy watching the drama unfold on the television. As a teenager I was disappointed to learn it was all a load of cinematic hokum, a fiction for 633 Squadron never existed. Only once I began my academic career and having undertaken much research on the Mosquito did I realise that the core elements of that film were based on fact. These included the Mossies remarkable low-level flying capabilities, the many successful precision attacks on German targets across occupied Europe, the sheer bravery of the pilots and 618 Squadrons real-life experimentation with Barnes Walliss Highball bombs. Today, the theme tune to 633 Squadron is a car-journey favourite with my own boys, while it seems that when the X-Wing in Star Wars was conceived, George Lucas had the Mosquito in mind. The climactic scenes of 633 Squadron , with model and real Mosquitos flying down a fjord to drop their bombs and seal up the entrance to the Nazi factory, were transplanted to Star Wars , while the trench run assault on the Death Star recaptures some of the sheer flying ability of the Mosquito.

Pound for pound the Mosquito was the most effective British bomber of the Second World War. The aircraft excelled as a precision attack bomber, while its ability to find and hit specific targets found it often deployed in pathfinding roles ahead of a main bomber stream comprising heavies such as the Lancaster, or co-ordinating the main bomber stream as a Master Bomber. The Mosquito itself could carry a 4000lb cookie bomb and could be adapted to carry Barnes Walliss Upkeep mine or Highballs to attack German capital ships (leading warships). It was often deployed where accuracy was at a premium, such as in the bombing of the Oslo Gestapo HQ in September 1942.

But the Mosquito was far more than an accurate bomber. Like many British aircraft of the Second World War it was marinised (fully adapted) for service at and from the sea. With the legendary Eric Winkle Brown at the controls, it was the worlds first twin-engine aircraft to deck land on a carrier. It could carry rockets, and could be armed with a six-pounder cannon, excelling once again as a ground attack aircraft. Its speed allowed it to operate as a fighter and, equipped with radar, it excelled as a night fighter. Speed and stability were also key in the Mosquitos photo-reconnaissance role and again in 1944 when it was tasked with stopping German V-1 rockets by flipping them with its wings. All this from an aircraft design so radical that the Air Ministry initially rejected it (who in their right mind would build an unarmed warplane?) and which was, when it finally went into production, built from wood. While the Lancaster was the heavy bomber par excellence, the Spitfire the alluring symbol of modernity, the Hurricane the real victor in the Battle of Britain, it was the adaptability of the Mosquito, a truly multi-role aircraft that made it the best British warplane of the Second World War.

Design history

Despite much theorising during the inter-war years, in 1939 the Air Ministry was still in a quandary about what it was looking for in bomber design. Nevertheless, in the minds of Air Ministry officials a bomber was generally slow-moving and lacking in manoeuvrability, heavily armed and of metal construction for its own defence and combat worthiness. Its job was, as air theorists predicted, to get through enemy defences and unleash its payload on targets in enemy territory.

What they were not looking for was a super-fast, wooden unarmed bomber. Yet in August 1936 the Air Ministry issued Specification P.13/36, formulated during the summer, for a quick (275mph) long-range (3000-mile) twin-engined medium bomber equipped with nose and rear turrets and with the capacity to deliver a substantial payload of 4000lb. This was the genesis of the Mosquito; however, its real origins can be found in the Air Ministrys desire to combine the four roles envisaged medium bomber, general reconnaissance, torpedo bomber and general purpose into one basic design.

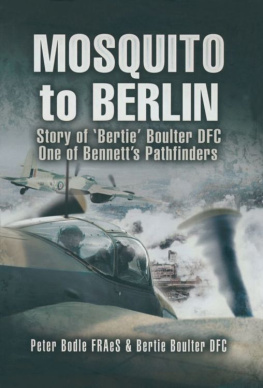

Mosquito Mk.XVI, ML963, 8K-K King of No. 571 Squadron, pictured around September 1944. 571 Squadron were a Pathfinder Squadron which operated as part of No.8 Pathfinder Group. ML963 conducted over 30 successful trips to Berlin.

De Havilland were not convinced the specification would produce an effective aircraft and believed it could not be done on two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. If it met the speed criterion the bomb load would have to be sacrificed, and vice versa. What was needed was either a compromise or a new way to approach the problem. Now the true genius of de Havilland and the Mosquitos chief designer Eric Bishop came to the fore. If all defensive armaments were dispensed with and the aircraft constructed from wood, the airframe would be lightened. The Air Ministry was less than impressed with the suggestion, but the need for British rearmament was pressing because of the growing threat from Nazi Germany. The pressure intensified after the events of 1938 at Munich and inventive solutions were required.

Throughout 1939 de Havilland continued to talk to the Air Ministry through Air Council Member for Research and Development Air Marshal Sir Wilfrid Freeman. Those conversations gained urgency with the outbreak of war. On 20 September de Havilland wrote to Freeman, outlining the idea for a wooden, unarmed twin-engined bomber, which was given the reference DH.98.

This proposal got things moving again, but the Air Ministry remained concerned about the DH.98s ability to continue flying faster than fighters. There was a subsidiary concern that a crew of just two would lead to unacceptable fatigue in the pilot and navigator, especially as the latter would take on bombing duties. The Ministry was still not convinced, clinging to the formula of a three-man crew for a bomber or using the de Havilland DH.98 proposal for a two-man light reconnaissance plane. There was still concern over the whole concept of an unarmed bomber. Nevertheless, models of DH.98 were sent for wind-tunnel testing with favourable results. But there was really only one way for de Havilland to prove the versatility and suitability of the concept and that was to build a prototype. Freemans support was crucial; without his firm commitment to the concept the Mosquito would likely never have been built.