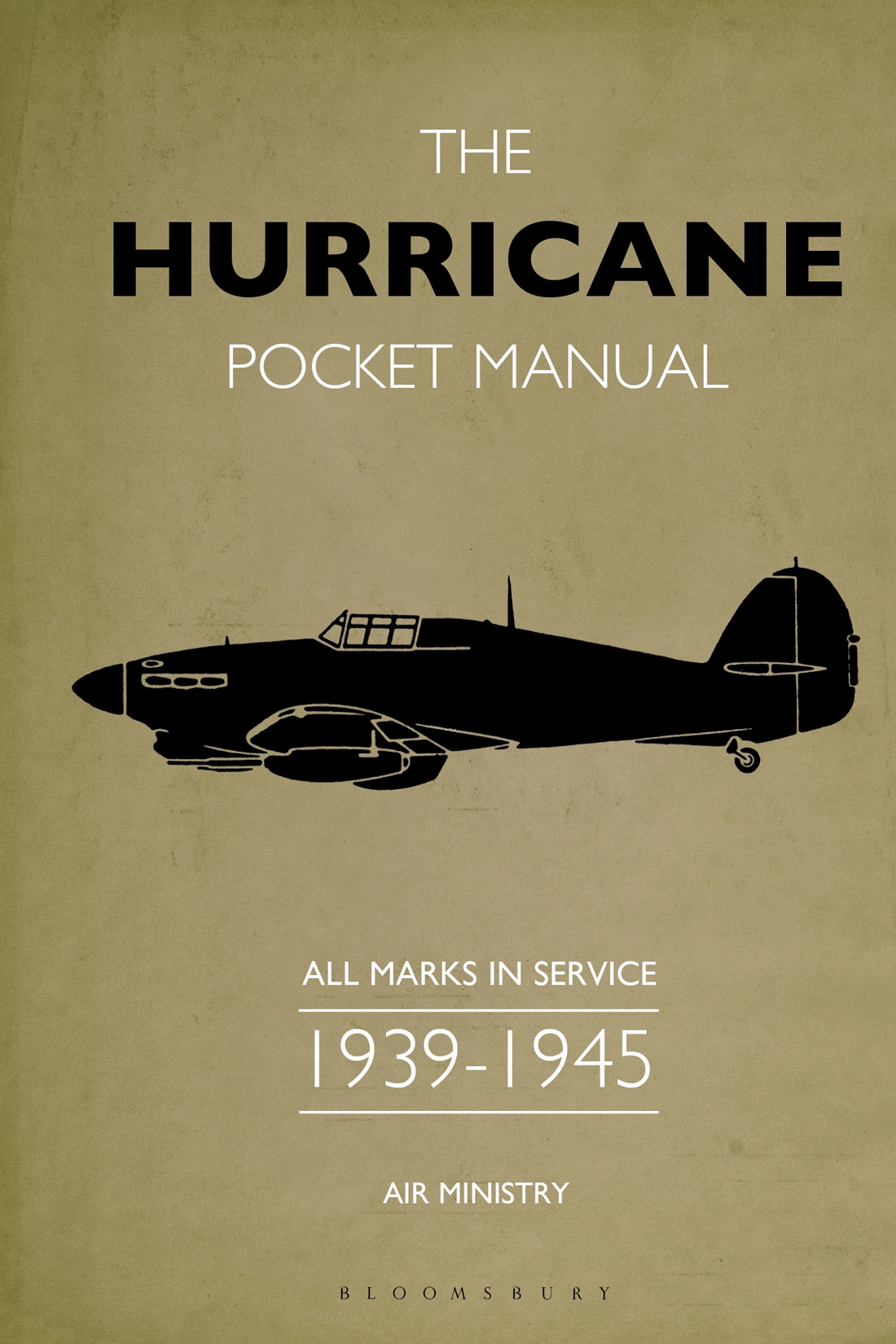

THE

HURRICANE

POCKET MANUAL

COMPILED AND INTRODUCED BY MARTIN ROBSON

My humble thanks go to a number of people who have provided assistance during the writing of this book. A number of my former colleagues at the Defence Studies Department at the Joint Services Command and Staff College were keen to see me continue my interest in aviation subjects, in particular Dr David Hall, Squadron Leader Hedley Myers and Squadron Leader Graham OConnor. The staff of the JSCSC library provided much assistance during a research trip in the summer of 2015. The staff of The National Archives, Kew, have again provided excellent service in handling persistent queries and orders of large boxes of Air Ministry files. I must also thank Melanie Thomas and Dave Bostock for helping me out during my Research trip to Kew. My former publisher John Lee must be applauded for the shared vision to get this pocket book series off the ground. At Bloomsbury Lisa Thomas has displayed much patience and her colleague Penny Hurricane Phillips has proved an enthusiastically excellent editor. As ever, Charlotte proves to be a highly knowledgeable sounding board, and Harry and Lysander are starting to understand the allure of anything powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

Martin Robson, Ide, November 2015

Contents

The Hurricane was our faithful charger and we felt supremely sure of it and ourselves

Wing Commander Peter Townsend

It was the plane that won the Battle of Britain

Flying Officer Ben Bowring, 111 Squadron

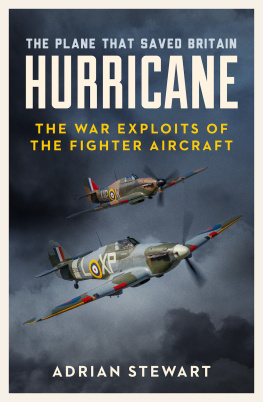

One question remained in my mind during the research and writing of this book. The Hawker Hurricane was loved by the majority of its pilots, and it comprised 63 per cent of Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain in the late summer of 1940 so why was its contribution to that epic fight with the German Luftwaffe and to the overall British war effort overshadowed by the Supermarine Spitfire? In part the answer lay in the Spitfires alluringly radical, almost sensual, lines and its performance, especially its speed. Perhaps more important was the perception of the Spitfire in the minds of the general public (in part fostered by the British Government) and in the minds of the enemy. While German pilots were happy to admit to having been shot down by a Spitfire (the wonder weapon excuse), it was almost humiliating to be shot down by a Hurricane, yet this aircraft accounted for 61 per cent of Luftwaffe losses in 1940.

Such perception belittles one of the most successful and, for the late summer of 1940, most important aircraft designs ever to have made it off the drawing board. But it is typical for the history of an aircraft that is riddled with paradoxes. Equipped with a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and mounting eight .303 Browning machine guns in her sturdy wings, the Hawker Hurricane traced its origins back to the biplanes of the First World War. It was very much a fusion of the old-fashioned and the new, modern age. By the time of the Battle of Britain, although the design had reached its technical limit, Fighter Command could muster 1,715 Hurricanes to combat the German threat. It was by no means a gold-plated solution to the problem of intercepting enemy aircraft, but the Hurricane was good enough and far easier to produce than the Spitfire.

Obtaining precise production figures is notoriously difficult, but a good enough figure is a total of 14,533 Hurricanes produced between 1937 and 1944. Those Hurricanes saw service throughout the war, and the Hurricane story falls neatly into two distinct phases as recounted by former Hawker test pilot Philip G. Lucas. Phase one was the development of the airframe as an interceptor and its performance in that role during operations in France, Norway and the Battle of Britain. The second phase saw the Hurricane superseded as an interceptor but finding a new lease of life in the form of the Mark II, with a Merlin XX engine armed with cannon, rockets and bombs as flying artillery, providing Close Air Support to Allied troops on the ground in North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Far East until the end of the war.

If the Spitfire can be considered a pilots dream, an aircraft for flying , then the wartime service and testimony of its pilots confirm the Hurricane as a superb fighting airframe. To understand why, we must trace the development of the Hurricane back to its origins in the mind of her designer Sir Sydney Camm. Camm began his design career working on biplanes during the First World War and by 1925 had worked his way up to become chief designer at Hawker, a post he would hold for forty years, ending his tenure working on the revolutionary Hawker Harrier in 1965. In an era of boffins, Camm fitted the stereotype perfectly. Driven, irascible, idiosyncratic (bizarrely for an aircraft designer he had a marked aversion to using wind tunnels) and at times a nightmare to work for and with, he had the necessary sheer bloody-mindedness to know that he was correct and to take on an Air Ministry and politicians searching for a cohesive and logical airpower strategy. Air theory in the inter-war years focused on the inevitability of the fact that, in Stanley Baldwins words, the bomber will always get through any air defence. Moreover, the political classes were late to wake up to the threat posed by the Fascist powers rearming and flexing their muscles during the 1930s.

It is in that context that the history of the Hurricane must be assessed. In 1930 the Air Ministry circulated Specification F.7/30 for a single-seater fighter capable of 250mph. Camm responded with a biplane design, the P.V.3, which was rejected. Undaunted, he went in a different direction, submitting a design for a single-seater monoplane development of the Hawker Fury biplane, but in the spring of 1934 that too was rejected. He revised the design again, this time including retractable wheels; they required a new and thicker wing root, which had the effect of providing the design with a strong undercarriage. Propulsion would come from a new engine designed by Rolls-Royce, the PV-12. Test details of this engine, later known more famously as the Merlin, were made available to Camm.

In September 1934 Camm submitted the revised design to the Air Ministry, who were impressed by the potential speed of nearly 300mph. This piqued their interest especially as they were aware of the problems Supermarine were experiencing with their design to Specifications F.7/30 and F.37/34 (for details see The Spitfire Pocket Manual ), which would eventually be christened the Spitfire. Hawker would benefit from a growing awareness within the Air Ministry and political elite that Britain was woefully short of fighters, and that the resulting expansion of the RAF would call for aircraft with which to equip squadrons. Camms design was concurrent with, but not a direct response to, the Air Ministrys Specification F.5/34 which called for an eight-gun day fighter to replace the Hawker Fury. Camm was still designing an airframe to house four .303 Browning machine guns. A meeting on 10 January 1935 between the Air Ministry and Hawker consolidated the two different strands into Camms design often referred to as Specification F.36/34 even though the written specification was not issued, as the design was already in circulation. The most important aspect, however, of all this was the ordering and construction of a prototype, K5083.

In July 1935 the Air Ministry issued a contract to Hawker to supply an eight-gun Hurricane. On 6 November 1935, K5083 took to the air with George Bulman, Hawkers Chief Test Pilot, at the controls. After the Hurricanes first flight, Camm climbed on to the K5083 wing desperate to hear what Bulman thought of his creation. Its a piece of cake, Camm recalled Bulman exhorting; I could teach even you to fly her in half an hour, Sydney. There were teething troubles: the Hurricane had a fixed-pitch propeller, which meant it was a little sluggish during take-off though this was later resolved with the fitting of variable-pitch propellers and then the Rotol constant-speed propeller. There were teething troubles with the Merlin engine itself. Nevertheless, following trials at the AEE at Martlesham Heath, the Air Ministry were keen for the Hurricane to enter production and on 6 February 1936 placed a provisional order for 600. (At the same time, 300 Spitfires were ordered.) The Air Ministry required a number of changes to the original design for the production model and a particular specification, 15/36, was issued on 20 July 1936. A little over a year later, on 8 September 1937, the first production model, L1547, was available for the RAF. Given the urgent need for pilots to gain airtime with the new aircraft, the Hurricane entered operational service on 15 December 1937 when 111 Squadron became the first RAF unit to receive it.