Table of Contents

Contents

To the families of those murdered on Air Indias Flight 182,23 June 1985

F IFTY YEARS HAVE PASSED since the campaign for a sovereign Sikh state went global. On 12 October 1971, the patriarch of the movement, Dr Jagjit Singh Chauhan, placed an advertisement in TheNew York Times proclaiming the birth of Khalistan.

Today we are launching the final crusade till victory is achieved, Chauhan announced. We are a nation in our own right. He then declared himself to be its first president.

Half a century later, the crusade is a smouldering wreck, haunted by the ghosts of thousands who died for nothing. The victims of the struggle for Khalistan were mostly Sikhs, who were supposed to be its beneficiaries. Yet a politically plugged-in band of separatists still keeps the cause alive in the Sikh diaspora, teaching their children that Khalistani killers were heroes.

This book takes a close look at the killers and their cause, revealing not only how they botched it but, equally, how governments from India to Pakistan to Canada bungled their response. For all sides, Khalistan became a case study in how not to do it.

A T THE AGE OF twenty-eight, an optimistic Sikh named Balraj Deol made a mistake which nearly cost him his life. He publicly joined some Hindu friends in supporting a compromise to give peace a chance in his homeland of Punjab.

Three nights later in a parking lot, he encountered five Sikh youths with a different opinion, which they expressed with hockey sticks and baseball bats. Deol tried to protect his head with his hands but the blows smashed his fingers and cracked his skull. He passed out and his attackers left him for dead. Yet, as they fled into the dark, Deol regained consciousness and still had one working limb. Both arms, both hands and his right leg were shattered, but he somehow dragged himself to the lobby of his apartment building. A woman spotted him and called for help. With some screws and a steel plate, doctors stitched him together.

So Balraj Deol survived the curse of Khalistan. Thousands of others did not.

In that summer of 1985, when busloads of innocents were shot and a packed airliner was blasted out of the sky, one vicious beating in suburban Toronto was a small story a footnote in the blood-soaked struggle for an independent Sikh state. But, in addition to blood, the beating of Balraj Deol had all the usual features of that quest for the Land of the Pure Khalistan.

The first standard feature of the attack was its futility. It achieved nothing. A Sikh state is still nowhere in sight and, thirty-five years after he was beaten to a pulp, Balraj Deol still condemns violence. The Khalistan campaign seems to be cursed doomed and denounced by the Sikhs it claims to defend.

For another thing, the justice system also achieved nothing. Again and again, the thugs got away with it. Deols assailants just graduated to bigger atrocities and are now revered as martyrs by a new generation of Khalistanis.

A third familiar theme: no talking. Nobody tried to reason with Deol or to explain how the killings in Punjab would deliver a better future. Blunt force was the first and only resort.

The fourth typical aspect of the beating was that the victim, like the attackers, was a Sikh. In more than a decade of violence in the name of a Sikh state, that pattern held: most of the dead were Sikhs.

For the maimed and the bereaved, it must have seemed that the glory days of the Sikhs lay not in the future, but in the past.

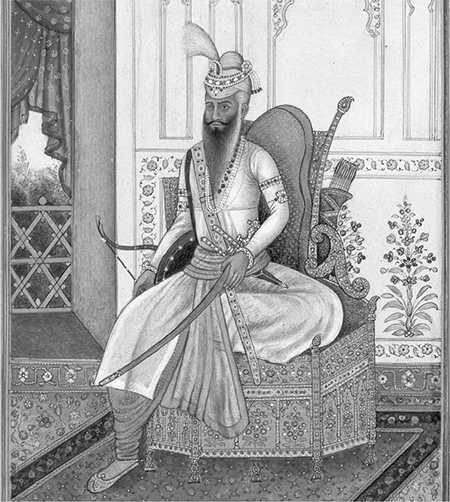

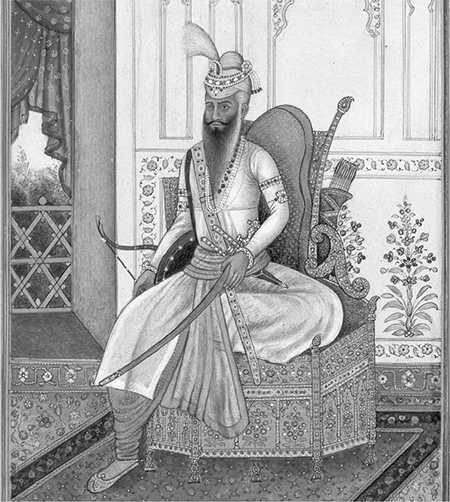

T WO HUNDRED AND TWENTY years ago, a wily, one-eyed Sikh warrior known as the Lion of Punjab, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, forged a dozen Sikh-ruled confederacies into a Sikh Empire stretching from the Khyber Pass to western Tibet. From his capital at Lahore, in todays Pakistan, he battled to expand his realm, kept the British at bay and cemented his alliances by marrying early and often.

Both the Maharaja and his empire thrived by force of will. Ranjit Singh lost his left eye to smallpox as an infant, survived his first assassination attempt at thirteen, married at fifteen and was eighteen when he developed a lifelong affection for strong drink yet he lived, by his sons account, to have forty-six wives and companions. Some were Muslim ladies, some Hindu and some, like him, were Sikh. His court hummed with variety and he showered patronage on poets and scholars who wrote books he could not read. But he lacked only formal education, not intelligence or vision. European generals trained his army, in which men of all faiths served, while the Lion of Punjab donated gold for Muslim mosques, Hindu temples and Sikh gurdwaras alike including the superb Golden Temple at Amritsar. In 1813, he even took possession of the storied Koh-i-Noor diamond, by extorting it from a fugitive king of Afghanistan.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh

Source: Col. James Skinner, Tazkirat-al-Umara, British Library

Even his demise was a drama. When he died of drink in 1839, it was said that four Hindu wives and seven concubines committed sati by loyally hurling themselves onto his funeral pyre. There should be a movie and, of course, there

Such tales make the reign of Ranjit Singh a golden age to reimagine indeed, Khalistanis today invoke it to demand the re-establishment of Sikh sovereignty. But, as empires go, it was very brief. The Sikh Empire lasted only while the Lion himself held sway over it, from 1799 until his death forty years later. After that, the British marched in, grabbed the Koh-i-Noor for Queen Victoria and absorbed the Sikh Empire into their own.

That unwelcome embrace endured for a hundred years and ended in horror. Indeed, the British may have been the original curse of Khalistan. Ever since they carved it up, too many quests for glory in Punjab have come to ruin.

T HE CURSE CAME EARLY for Intekhab Ahmed Zia at 5.30 in the morning.

He was still in his twenties, but Zia had already made a name for himself in Pakistan not just as a dedicated Islamist but as the man to know in Lahore for Sikh and Kashmiri militants fighting against India. Zia was an educated, wealthy young man who could connect them with the powerful Inter-Services Intelligence agency of Pakistan, the ISI. Enemies of India could turn to him for help with weapons, medical care or safe haven.

Pakistans leadership had long seen the Khalistani breakaway movement as useful one more stick with which to beat India. For Intekhab Zia, though, navigating the jungle of gunmen and spies in Lahore was one thing but now, in October 1992, he was in much deeper waters. He had ventured illegally into India to join an international terrorist with a horrifying record a man who had slaughtered 300 innocents with a single bomb.

Officially, Zia was visiting relatives in India. He didnt have any, but never mind; the Pakistani foreign ministry said he was an innocent tourist with no terrorist linkages whatsoever. If so, he was a tourist with a rocket launcher in his car. Whats more, his infamous companion was no less than the self-styled living martyr of the Sikhs, Talwinder Singh Parmar. It was Parmar who now led Zia to a real and messy martyrdom.

The Sikh independence struggle was sputtering in 1992 and the Punjab police, mostly Sikhs themselves, were not gentle not after 1,400 of their fellow officers and many of their family members had been killed by separatists trying to smash the rule of law in Punjab. But, on the morning of 15 October, the police had the advantage. An informer had tipped them off that Parmar and a gang of gunmen had been seen in a pair of Maruti cars near the town of Phillaur, not far from Ludhiana. Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) Satish Kumar Sharma ordered a net of early-morning roadblocks to catch them.