For Hana Kantor,

my grandmother and a survivor among survivors

And for Ron Lieber, my husband

I NTRODUCTION

One late September afternoon in 2009, Barack and Michelle Obama were sitting together in the gold-and-ivory splendor of the Oval Office, discussing the most personal of matters in the most official of settings. I was interviewing them for an article in the New York Times Magazine about their marriage, and as they sat in matching striped chairs, Gilbert Stuarts portrait of George Washington watching over them, they spoke about their partnership.

The president was analytical that day, the first lady funny and expressive. But it was clear that the perfect-seeming couple that had glided across the dance floor at the inaugural balls nine months earlier were still privately grappling with the very fact of being president and first lady. Michelle Obama said she still asked her husband, whenever she found him seated behind John F. Kennedys desk, a few feet away, What are you doing there? Get up from there! When I asked how it was possible to have an equal marriage when one person was president, the first lady let out a sharp hmmmpfh, as if she were relieved someone had finally asked, then let her husband suffer through the answer. It took him three stop-and-start tries. My staff worries a lot more about what the first lady thinks than they worry about what I think, he finally said, before she rescued him with an answer about how their private decisions were made on an equal basis.

A few moments later, the president made the implausible case that his wife should be somehow walled off from political culturethe silliness of Washington, he called it. Yet when she insisted that she was wholly uninterested in politics or policy, he eyed her with a bemused expression and gently contradicted her, saying he relied on her feel for public opinion on every domestic policy issue.

After the article was published, I couldnt stop thinking about the subtle tension I had felt in that room. Some of it was between the Obamas themselves. But the real mismatch was between the first couple and the world into which they had catapulted themselves. For all of their ease together in public and the stunning ambition they had shown in pursuing the presidency, the Obamas were not entirely comfortable with the bargains they had made.

How could they be? At the start of the presidential race in 2007, the candidate everyone still called Barack was just two years out of the Illinois State Senate, while his still-unknown wife bought her size-ten shoes on the Nordstrom sale rack, knew her way around a McDonalds drive-thru menu, and expressed little desire to live in Washington. Back then, they seemed like the rare political couple who were residents of our world, not a universe of green rooms, briefing books, and sycophantic handlers. They told us they were different from others in political life; they vowed to remain normal in the White House and to change the nations capital without letting it change them.

Now, after a career criticizing the establishment, Barack Obama was the establishment. He had little Washington, managerial, economic, or national security experience, and yet his agenda was vast, the countrys crises severe, his glow already dimming that autumn. He was a solitary figure in a job where emotional engagement, not just policy accomplishments, was essential to success. The Obamas had disappeared deep into the White House; their friends had become their staff, their children celebrities, their new dog the recipient of letters requesting his official portrait. By 2012, would they still be the couple we met in the 2008 race? How would they cope with the difficulties and failures that were just starting to come into view that fall? Had the Obamas freshness to political life really been an asset in the first place?

There was something else, too. The Obamas had spent their marriage debating how much change was possible within the political system and whether public life could be made livable. The first lady was the worrier, with little trust that government could create lasting change and fear that political life was inherently corrosive. I didnt come to politics with a lot of faith in the process, she had said years earlier. I didnt believe that politics was structured in a way that could solve real problems for people. The president didnt disagree, exactly; his critique of the powerful was nearly as unsparing. But he had an astonishing faith in his own abilities: he believed that he could solve those real problems; that together they could protect themselves from the toxic forces Michelle feared. He told the country, but also his own wife, that he could reconcile the seemingly irreconcilable: red and blue America, the legislative process and lofty goals, a political life and a private one.

The White House was already testing those promises severely. The strengths and challenges of our marriage dont change because we move to a different address, the first lady said in the interview. It was my first clue that the Obamas private debate hadnt ended on election night 2008that it continued in the White House, with greater force, scope, and complexity than ever.

Exploring the impact of the presidency on the Obamas relationship was not nearly enough, I realized. The question was too small. The more difficult question was the reverse one: the impact of their partnershiptheir debates and differences, shared ideas about themselves, and deep hesitation about politicson the presidency, the job of first lady, and the nation. In public, they smiled and waved, but how were the Obamas really reacting to the White House, and how was it affecting the rest of us?

I reported and wrote this book to answer those questions. I discovered an untold story of Michelle Obamas deep initial difficulty in the White Househer disorientation in a strange, confined new world, tense relationships with many of her husbands advisers, struggle for internal influence, and eventual turnaround. I also found that reporting on her was a way to better understand her elusive, introverted husband. She is his sparring partner, early-warning system, refuge, and guardiantougher, by his own admission, than he is. Hers are the ultimate standards he tries to live up to, with consequences we will be debating for a long time to come. Knowing her real experiences in the White House helps us understand not just one of the most influential women of our time but fresh and essential truths about her husbands tenure.

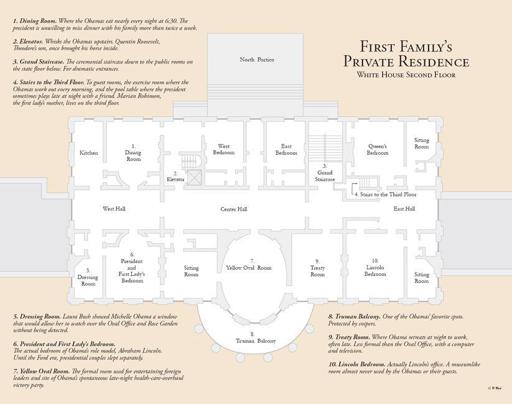

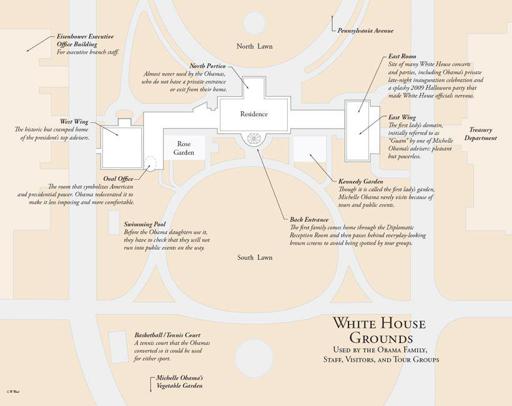

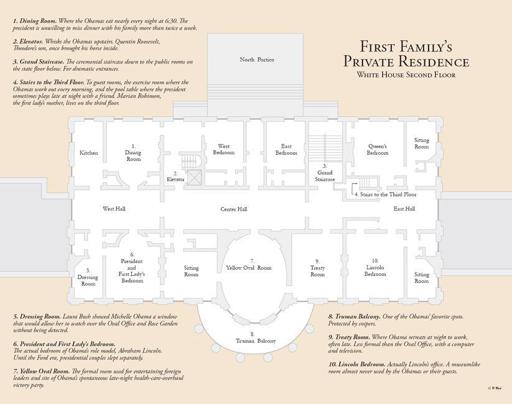

O NE OF THE STRANGEST THINGS about the presidency is how unsparingly intimate it is. The White House is an office, home, and museum all at once, those three functions constantly colliding. The president and first lady often hide just inches from public view. Their jobs are performed the same way, with little separation between public and private, political and personal. Instincts, aversions, blind spots, and vanities that would not matter much in ordinary workplaces have huge significance. Again and again, working on this book, I saw how the Obamas personal dynamic had consequences for the rest of us: a shared mistrust of politics so strong it sometimes hurt the presidency; the presidents often unrealistic assessments of what he could accomplish and the first ladys worry about them; the way the presidents career repeatedly required the first lady to take a backseat to him, and the various ways she has reasserted her power; their frequent desire for escape and relief from the life they worked so hard to attain; and the way Michelle Obama rescues Barack Obama, again and again, personally and politically. With many Americans frustrated with Obamas stewardship of the economy, his reelection in 2012 increasingly rests on attractive images and charming stories of him and his family, even though the true story of the Obamas in the White House is far more complex.

Next page