Also by Mary Frances Berry

And Justice For All: The United States Commission on Civil Rights and the Continuing Struggle for Freedom in America

My Face Is Black Is True: Callie House and the Struggle for Ex-Slave Reparations

The Pig Farmers Daughter and Other Tales of Law and Justice: Race and Sex in the Courts 1865 to the Present

Black Resistance/White Law: A History of Constitutional Racism in America

The Politics of Parenthood: Child Care, Womens Rights, and the Myth of the Good Mother

Why ERA Failed: Politics, Womens Rights, and the Amending Process of the Constitution

Long Memory: The Black Experience in America (coauthor, John W. Blassingame)

Stability, Security, and Continuity: Mr. Justice Burton and Decision-Making in the Supreme Court, 19451958

Military Necessity and Civil Rights Policy: Black Citizenship and the Constitution, 18611868

Also by Josh Gottheimer

Ripples of Hope: Great American Civil Rights Speeches

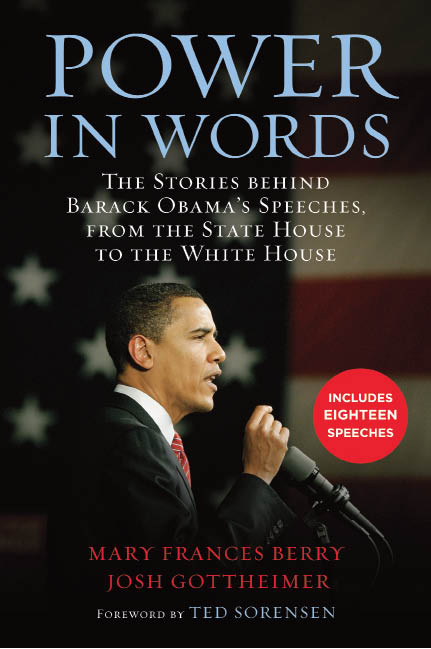

Power in Words

The Stories Behind

Barack Obamas Speeches,

from the State House

to the White House

Mary Frances Berry

Josh Gottheimer

Foreword by Ted Sorensen

Beacon Press

Boston

To my two girls, Marla and Ellie

J.G.

To my brother Troy

M.F.B.

For the power of their words

The new circumstances under which we are all placed

call for new words, new phrases,

and for the transfer of old words to new objects.

THOMAS JEFFERSON

Contents

Foreword by Ted Sorensen

The American presidential election of 2008 was historic for many reasons: it was the first election of an African American president; the second election of a non-WASP (the first was John F. Kennedy, in 1960); and the surprise election of a young, progressive Democrat after Republican domination of the modern presidential electoral process. With the possible exception of Bill Clintons victory in 1992, the election of Obama was also the first presidential election since Kennedys narrow triumph over Nixon in 1960 in which the victors campaign oratory was a principal reason for his success.

Obama embodied change, not only with his skin color, his youth, and his newness to the American national political scene, but also with his fresh approach to politics embodied in the themes of his speeches. He reached out to scholars and intellectuals for the expert advice reflected in his thoughtful speeches. Occasionally, as a consequence, some of his speeches seemed aimed more at members of a university faculty or newspaper editorial board than at typical American voters. He refused to talk down to voters, or to dodge difficult issues, or to revert to the worn slogans and clichs that often define political rhetoric. His principal opponent for the Democratic Party nomination, Hillary Clinton, was a better debater; was better prepared, being ready with five-point programs and proposals to meet any issue; and had a special appeal to female voters and loyal Clinton admirers. But she did not represent change.

Neither did Obamas opponent in the general election, John McCain, who would have been the oldest person elected president had he succeeded. McCain was an honorable man with a long record of service and dedication to this country, but he did not prove to be an effective campaigner, and his faltering, sometimes even bewildering, rhetoric could not compete with the clear and forceful messages emanating from the Obama camp.

Obama is a naturally eloquent man, as he often demonstrated when speaking with no prepared text in front of him and in the inevitable spontaneous situations that arise on the campaign trail and its hundreds of formal and informal press conferences. In addition to his own talents, he could rely on a gifted team of speechwriters, some of whom continue to play an important role in the White House today: Jon Favreau, his chief speechwriter; Ben Rhodes, his foreign policy specialist; Adam Frankel, one of his earliest campaign speechwriters; and, later, draftees from the Hillary Clinton campaign. (Adam Frankel is also a personal friend of mine, having served as my principal research assistant in the preparation of my recent book of memoirs, Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History. ) Once again, we have a president who speaks on current controversies at home and abroad and on major issues in his legislative program. The world once again depends upon the leadership of the United States and its president, both in strengthening the global and American economies and in restoring law and diplomacy to world affairs.

Obamas campaign speeches, carefully compiled and analyzed in this volume, were the first indication that he would rank with Jefferson, Lincoln, Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and Kennedy as a president whose oratory the world would hear and remember. Like those eloquent presidents, Obama is neither the tool nor voice of his gifted speechwriters. By nature a leader, a thoughtful decision-maker, and a listener who knows how to draw the best judgment and recommendations from those whom he invites to his table, he has appointed a superb team of advisers to his cabinet and administration. I predict a historic administration, for which this book will long serve as a reference to be consulted by current politicians and future historians.

Introduction

Its fair to say that when it comes to politics, there are few things Americans agree on. That said, there is one thing thats not debatable: Barack Obama can deliver one hell of a campaign speech.

Even those who dont agree with his policies can recall the first time they heard Obama, the candidate, thunder away to a crowd of adoring listeners. For many, the first time they heard Obama was his call for hope and unity at the 2004 Democratic National Convention; for others, it was the first time they heard his now-famous mantra, Yes, we canwith its roots in Cesar Chavezs 1972 S, se puede campaignon the evening of the New Hampshire primary. There are few politicians in American history who have used the stage more effectively.

You may have a different view of Obama the president and of his rhetoric in the White House. You may not agree with his policies, or you may believe, like some, that he has overused the presidential podiumor that his deeds have fallen short of his words. You may believe that his signature promises of change and political unity have given way to traditional stagnation and partisanship.

We will leave it to history, and to another author, to judge his presidency, because one thing is clear: the rules of governing are much different than those of campaigning.

Presidents have different agendas from candidates. Candidates must convince the public to vote for them, and the press to adore them; a candidates agenda is not to convince the Congress or the special interests to pass legislation. They are firing up a crowd at a rally of screaming supporters, not delivering a sober speech from the Oval Office on an impending war.

Presidents, on the other hand, have to be much more careful with their rhetoric; a single word can impact financial markets and foreign affairs. They have to push their budget policies day in and day out, even if its tedious and the public is bored stiff. As Peter Baker wrote in the New York Times, Speechmaking as a president often presents a sharper challenge than it does on the campaign trail. The audience is different, the desired goals are different, the platform is different... and pushing policies requires more explanation than inspiration.

This book covers a period of time that is already inscribed in the annals of politics: the rise and rhetoric of Barack Obama from state senator to president of the United States. It uses eighteen of Obamas most important political speeches to tell the story of his remarkable ascent and his unprecedented use of the podium to win over a strong majority of the American public. As you will see, its not just about the words themselves, but the stories behind themwhy they were chosen, how they were shaped, and their impact on the race.