Table of Contents

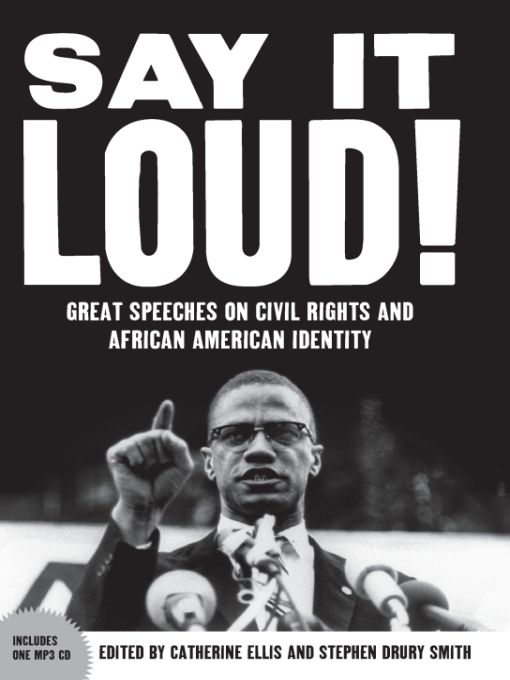

Also by Catherine Ellis and Stephen Drury Smith: Say it Plain: A Century of Great African American Speeches

This book is dedicated to

Jackie Ellis and Oleg Svetlichny,

John Ellis and Elaine Hirschl Ellis,

Janet Evans Smith and Robert Drury Smith

PREFACE

This is the second anthology of great speeches by African Americans meant for the eye and ear. Our first book/CD project, Say It Plain, chronicled an array of black leaders across the twentieth century exhorting the nation to make good on its promise of democracy. This collection opens in the middle years of the modern civil rights movement. It captures speeches by an eclectic mix of African American orators arguing about how best to pursue freedom and equality in a nation still deeply marked by racial inequities.

Say It Loud is titled after the classic 1969 James Brown anthem Say It Loud, Im Black and Im Proud. This anthology is meant to illuminate the evolution of ideas and debates pulsing through the black freedom struggle from the 1960s to the present and the way these arguments are suffused with basic questions about what it means to be black in America.

As with our first book, these words were meant to be heard. You can listen to excerpts of all but one speech on the CD that comes with this book. Each address was recorded at a live event, such as a rally, funeral, or graduation ceremony. Sometimes the speech was directed strictly at African Americans and at other times to a broader racial mix. In any case, these impassioned, eloquent words continue to affect the ideas of a nation and the direction of history.

The one speech missing from the excerpt CD is Ossie Daviss eulogy for Malcolm X. To our knowledge, there is no recording of the original speech made in Harlem in 1965, which Davis wrote out the night before the funeral. (Davis later recorded the eulogy for Spike Lees film, Malcolm X. ) Even so, we were eager to include Daviss moving address in this collection.

We also wish to note that there were a number of historic and exciting speeches that we wanted to include in this collection but could not. In some cases, the cost of publication rights was beyond the reach of this nonprofit project. Also, there are the limits of space. Say It Loud is not a complete catalog but a representative sampling of the rich, sophisticated, and often contentious dialogue about civil rights and African American identity in the past fifty years.

A Note About Transcripts

The transcripts for this book were drawn from audio and video recordings. In some cases, we were able to start with existing transcripts in the public domain and check them against recordings. At other times, we produced the transcripts ourselves, with the help of dedicated colleagues. Each transcript here has been checked against the recordings by at least two sets of ears. Occasionally, words in some of the recordings are hard to hear. Weve used our best judgment to make the most faithful transcripts we can.

Catherine Ellis and Stephen Drury Smith

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are deeply grateful to the people who helped with this book/CD and documentary project. Chief among them is our editor at The New Press, Marc Favreau, a patient and enthusiastic guy. Our editor at American Radio Works (ARW), Catherine Winter, lent her tremendous skills to this book and our writing.

We thank other talented members of the ARW team who helped in transcribing speeches, gathering permissions, and producing the companion radio documentary and Web site. They include Ellen Guettler, Suzanne Pekow, Frankie Barnhill, Ochen Kaylan, Tricia Kostichka, and Emily Torgrimson. At American Public Media, Sarah Lutman and Judy McAlpine generously supported this project. Rachel Reinche and Mitzi Gramling provided essential legal help.

Thanks go to the librarians and archivists who helped us unearth important speeches. They include Kenneth J. Chandler, archivist of the National Archives of Black Womens History; Joellen El Bashir, curator of Manuscripts, and Tewodros (Teddy) Abebe, assistant archivist, at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University; Chuck Howell, curator at the Library of American Broadcasting; and Brian De Shazor and the staff at Pacifica Radio Archives. Thanks, also, to documentary producer Shola Lynch.

We are indebted to the speakers, or their heirs, who granted us permission to include their words in this book. This collection is theirs.

Finally, a shout-out to our children, Henry, Ben, Nina, and Kobe. You are always, always in our hearts.

MALCOLM X (1925-1965)

The Ballot or the Bullet

King Solomon Baptist Church, Detroit, MichiganApril 12, 1964

Malcolm X was one of the most dynamic, dramatic, and influential figures of the civil rights era. He was an apostle of black nationalism, self-respect, and uncompromising resistance to white oppression. Malcolm X was a polarizing figure who both energized and divided African Americans, while frightening and alienating many whites. He was an unrelenting truth teller who declared that the mainstream civil rights movement was nave in hoping to secure freedom through integration and nonviolence. The blazing heat of Malcolm Xs rhetoric sometimes overshadowed the complexity of his message, especially for those who found him threatening in the first place. Malcolm X was assassinated at age thirty-nine, but his political and cultural influence grew far greater in the years after his death than when he was alive.

Malcolm X is now popularly seen as one of the two great martyrs of the twentieth-century black freedom struggle, the other being his ostensible rival the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. But in the spring of 1964, when Malcolm X gave his Ballot or the Bullet speech, he was regarded by a majority of white Americans as a menacing character. Malcolm X never directly called for violent revolution, but he warned that African Americans would use any means necessaryespecially armed self-defenseonce they realized just how pervasive and hopelessly entrenched white racism had become.

He was born Malcolm Little in 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska. His father, Earl, was a Baptist preacher and follower of the black nationalist Marcus Garvey. Earl Littles political activism provoked threats from the Ku Klux Klan. After the family moved to Lansing, Michigan, white terrorists burned the Littles home. A defiant Earl Little shot at the arsonists as they got away. In 1931, Malcolms father was found dead. His family suspected hed been murdered by white vigilantes. Malcolms mother, Louise, battled mental illness and struggled to care for her eight children during the Great Depression. She was committed to a state mental institution when Malcolm was twelve. He and the other young children were scattered among foster families. After completing the eighth grade, Malcolm Little dropped out when a teacher told him that his dream of becoming a lawyer was unrealistic for a nigger.

As a teenager, Malcolm Little made his way to New York, where he took the street name Detroit Red and became a pimp and petty criminal. In 1946, he was sent to prison for burglary. He read voraciously while serving time and converted to the Black Muslim faith. He joined the Nation of Islam (NOI) and changed his name to Malcolm X, eliminating that part of his identity he called a white-imposed slave name.