Copyright 2012 by BlueRed Press Ltd.

This Lyons Press edition first published in 2012 by arrangement with Blue Red Press Ltd.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Text by C. Edwin Vilade

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

When Abraham Lincoln rose to address the assembled crowd after taking the oath of office as president, he began by stating that he was doing so in compliance with a custom as old as the government itself. He was correct. Over more than two centuries since the election of George Washington, presidents have addressed the American people thousands, if not tens of thousands of times. Although they direct their words to the audiences seated and standing in front of them, all presidents have been aware that their words would eventually reach to the furthest corners of the ever-expanding country. Direct communication between the chief executive and the citizenry is a bedrock tradition in America, and a hallmark of democracy.

The first presidential address was delivered by George Washington at his inauguration on April 30, 1789. In the flowery style of the day, he said almost nothing but took more than 1,400 words to say it. He simply invoked the blessings of God and indicated his willingness to work with the Congress. But in delivery of an inaugural address, as in so many other matters during his two terms in office, he established a precedent that has endured to this day.

If George Washington confined himself to ambiguous niceties during his first speech as president, his final one was much more substantive. He established another traditionthe presidential farewell address. That tradition has not always been followed in the centuries since. Some unsuccessful presidents have slunk out of town without a word, while othersmost tragically those such as Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedyhave been denied the opportunity. The most memorable farewell since Washington was delivered by a president not known for his eloquence, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

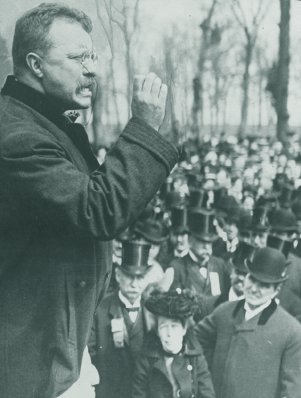

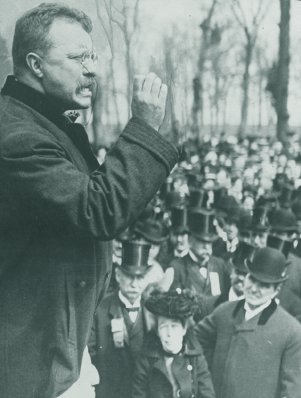

President Theodore Roosevelt forcefully speaking to a crowd.

In his farewell, Washington spoke at length of his hopes for the future of the country, and issued warnings that have remained influential in shaping the policies of the US government ever since. In the intervening two centuries, other presidents have spoken enduring words that have influenced the course of the country. One of the purposes of this volume is to examine those important speeches, the issues and situations that prompted them, the ways in which they changed between concept and delivery, and their impacts.

In his farewell, Washington also established another practice that has been followed ever since, at first quietly and later openly: he had help in composing the address. James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, among the most prominent of the Founding Fathers, were also arguably the first presidential speechwriters. Each submitted a draft of Washingtons farewell, and some of the language of each was used.

Neither, of course, claimed public credit for his contribution. Scholars have had to comb through the correspondence and the papers of all three and their contemporaries to determine the process of development of the speech. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as indeed since the days of Greece and Rome, public men were presumed to have composed their own speeches. A man who could not write and deliver a stirring address was at a great disadvantage in pursuing a political career.

Many of the Founding Fathers of the United States were somewhat flawed in this regard. Thomas Jefferson and Madison were superb writers, for example, but were somewhat lacking on the platform. Jefferson clearly wrote his own inaugural addressit ranks among the very bestbut did not like to speak in public. He established the practice, which endured for more than one hundred years, of delivering the State of the Union message to the Congress in writing, rather than orally.

James Monroe, on the other hand, has been judged by history as something of an intellectual lightweight. Questions have persisted as to whether he, or his secretary of state and successor John Quincy Adams, actually wrote what has become known as the Monroe Doctrine. Adams clearly contributed, but Monroe scholars are adamant about his primary authorship.

Even presidents who are demonstrably eloquent have turned to others for help and advice. Lincoln, undoubtedly the most elegant and poetic writer ever to occupy the office, sought assistance from William Seward, his new secretary of state and former political rival, in composing his first Inaugural Address.

Woodrow Wilson was also in the first rank of presidential writers and speakers. Nevertheless he had the help of no fewer than 150 scholars in composing his famous Fourteen Points for settlement of World War I.

The pretense of presidential self-authorship began to crumble after Wilson. Warren G. Harding, who followed Wilson, hired an old newsman named Judson Welliver as a congressional liaison. Wellivers role gradually evolved toward writing speeches before Harding died in office. Welliver was retained by Calvin Coolidge when the latter assumed the presidency.

Coolidge, a matter-of-fact New Englander, saw no point in disguising the nature of Wellivers duties, giving him the title of literary clerk. Welliver has thus been dubbed the first White House speechwriter.

Every president since has employed speechwriters more or less openly. Franklin Delano Roosevelt numbered two Pulitzer Prize winners among his many speechwriters. There is evidence, however, that Roosevelt contributed many first-rate phrases to his memorable speeches. One small example, contained in this book, is his alteration of a day that will live in history to a day that will live in infamy in his December 7, 1941, speech.

The proliferation of White House speechwriters has led to a proliferation of speech drafts. Harry S. Trumans and Dwight D. Eisenhowers most notable speeches, included in this volume, went through many drafts, and the development process is of interest. John F. Kennedys almost symbiotic relationship with his principal speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, was an exception to the rule of multiple authorship and review of speeches. The quality showed.

The trend toward institutionalization of the White House speechwriting process has continued in recent decades. Speechwriters are given assignments, produce drafts, and they are then subjected to a process called staffing, wherein the drafts are sent around to literally dozens of White House and Cabinet department experts. Each of these experts marks up the draft and the speechwriters incorporate the changes into the next draft to be circulated.