Contents

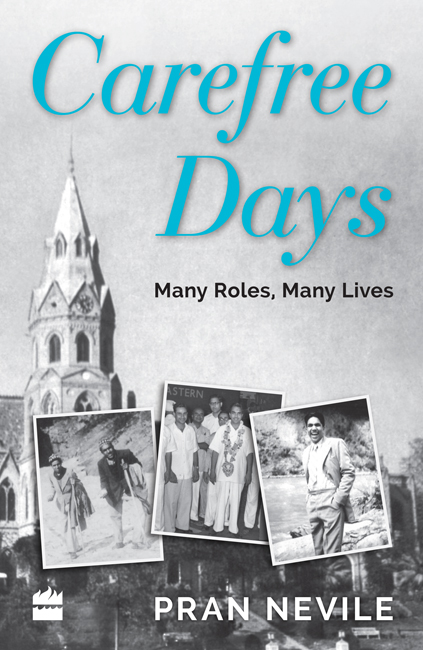

Carefree Days

MANY ROLES, MANY LIVES

Pran Nevile

HarperCollins Publishers India

Dedicated with love and respect to

the memory of my parents

Contents

L AST YEAR, I WAS REPORTED IN print as Indias oldest surviving author. This compliment galvanized me to complete my memoir rapidly. I have travelled eighty years into the past to recall the happenings in my long active life. It is a commonplace experience that our remembrance of events that took place fifty to sixty years ago is clearer than recent ones. But this delightful wandering of unfettered thoughts is an enjoyable exercise. Like an old picture, the recollections of early years often become dim and obscure, but some particular events remain so deeply impressed here and there that they defy the effects of time.

As one advances in years, one becomes increasingly detached from the current noise and turmoil, the concerns of the younger generations. I rejoice with the notion that the pleasant days of my long life are not over yet, and look forward to every dawn with delight and hope for some new thrill and joy.

Practically all my contemporaries, comrades and colleagues have already departed for the popularly termed heavenly abode. Those close to my fading age group often wish for dying in sleep, not realizing that death itself is a sleep in which there are no dreams.

The foregoing is not a relevant preface but then it is the last part of a book to be written, and is seldom read. All the same, the gentle reader should know something about this memoir. During more than seventy years of my multi-professional working life, I have been a journalist, research official, public sector manager, bureaucrat, economic diplomat, Soviet bloc expert, UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) adviser, freelance writer and author, art historian, chronicler of the Raj era, and protagonist of peoples music, which is my chief occupation at present. In this memoir, an effort has been made to narrate the story of my multi-professional, eventful as well as colourful life, which has been acclaimed as unusual and extraordinary.

I have done most of my writings in the congenial atmosphere of the India International Centre (IIC) library. I would like to express sincere appreciation for all the courtesies and assistance extended to me in my work by Dr S. Majumdar, chief librarian, and his team, especially Shefali Bhatt and Rajeev Mishra.

For the musical functions organized by me over the years I am deeply grateful to Premola Ghose, chief of Programme Division, IIC, and her colleague L.S. Tochhawng. Also, I would like to thank Shadab Hussain, Dr Chandrima Majumdar and Aditi Chauhan of India Habitat Centre (IHC) and Epicentre for their help in holding these functions. Sincere thanks are offered to Shalini Bhargava for critical appraisal of the functions and valuable suggestions.

I would like to mention that the idea of writing a memoir was initially planted in my mind by my eldest grandson Ravi and enthusiastically supported by other grandchildren Gaurika, Aditya and Anshuman. I am grateful to Madeeha Gauhar for her valuable suggestion to include a chapter on the Partition. Thanks should also go to Humra Quraishi for prodding me to complete this book as soon as possible. Further, I owe the greatest debt to my wife Savitri for her unflagging support throughout, until her passing away in 2013. I am also indebted to my daughters-in-law Madhulika and Megha for going through the manuscript and their overall assistance.

Finally, my grateful thanks go to HarperCollins Publishers and their former CEO, P.M. Sukumar, for evincing interest in my work. Special thanks are also due to Krishan Chopra and his team for their abiding interest in monitoring the progress of the book as well as his help and guidance in organizing its timely publication.

| Gurgaon | Pran Nevile |

| February 2016 |

I HAIL FROM A SMALL LANDOWNING family, and my grandfather, a Sanskrit scholar and astrologer, supplemented his income by teaching and training boys in the conduct of religious rituals and ceremonies, and preparing them for the priestly profession. My father, the eldest son, was one of the early boys to move to a town for high school education. Fortunately, he had an aunt living in Jalandhar, where he went after his middle school and passed the entrance (matriculation) examination. He was keen to study further but was unable to do so due to lack of resources and took employment in the postal department at Lahore. He was the first member of the family to turn a city dweller. I was born in 1922, nearly a decade after his moving to Lahore.

My earliest memory takes me back to my ancestral village Vairowal in Amritsar district. It was a unique village with several pucca houses and even brick-paved streets. It had a dharmashala with its own well that supplied drinkable water. This unusual environment of the village was attributed to the fact that Maharaja Ranjit Singh used to camp here during his hunting excursions. Vairowal boasted of a post office and middle school. It was dominated by the Sikh community of Bawa clan, who claimed their descent from Guru Angad Dev. Then there were some Hindu families and also Muslims who asserted their Rajput origin. The village residents were mostly landowners, big and small, who had leased out their lands to cultivators under the batai (crop sharing) system, which ensured a sizeable share for the landowners. The village was reasonably prosperous until the last decade of the nineteenth century, when the new generation started moving out to urban centres of Punjab in search of employment. The successive fragmentation of landholdings through inheritance made it difficult for families to survive with shrinking land income. Located in the heart of Maja segment of Punjab, the people of Vairowal had an inborn trait of enterprise and adventure. No wonder some of them settled in distant lands across the seas, thanks to the British colonial masters.

I vaguely remember my early childhood days when we lived in a rented house in Mohalla Mohlian inside Lahori Gate of the walled city. A four-storeyed structure, it was the tallest in the neighbourhood. There was then neither electricity nor house taps. Misars (professional water carriers) delivered water in large vessels from nearby wells, charging six annas (37 paise of today) per vessel on a monthly basis. For light, we managed with kerosene lamps of different shapes and sizes, the most common being the portable hurricane lamp of English make. The streets were also lighted with kerosene lamps, installed by the municipal committee, whose workers used to light them every evening and turn them off in the morning. By the 1930s we had electricity in the house. I vividly remember the landmarks of the neighbourhood. There was a popular akhara (wrestlers arena) run by one Gokal Pandit, who trained young wrestlers but was more known in the city for running a clinic for birds, treating those injured by the sharp twine of flying kites. Nearby was a cluster of Muslim professional printers of textile materials with their wooden blocks. Lahore boasted of a friendly division of occupations. The entire vegetable and fruit trade, and the bulk supply of milk to the citys halwais (milk and sweets vendors), mostly Hindus, were handled by Muslims who were also skilled craftsmen. An enterprising Muslim lady in our mohalla ran a tailoring shop at her house and womenfolk of all communities, wanting to avoid male tailors, flocked to her. Kite making, a big business in Lahore, was dominated by Muslims who were experts in the art.