The Tragedy of William Jennings Bryan

The Tragedy of William Jennings Bryan

Constitutional Law

and the Politics of Backlash

Gerard N. Magliocca

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW HAVEN & LONDON

Copyright 2011 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations,

in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the

U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press),

without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.S. office)

or (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Magliocca, Gerard N.

The tragedy of William Jennings Bryan : constitutional law and the politics of

backlash / Gerard N. Magliocca.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780300153149 (alk. paper)

1. Constitutional historyUnited States. 2. United StatesPolitics and government18651933. 3. Bryan, William Jennings, 18601925. I. Title.

KF4541.M273 2011

342.73029dc22

2010039781

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso Z39.481992.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso Z39.481992.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Guido Calabresi, who made all of this possible

The humblest citizen in all the land, when clad in the armor of

a righteous cause, is stronger than all the hosts of error.

WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN

Contents

Acknowledgments

Writing one book was so much fun that I decided to write another. I am reluctant to call this one a sequel, as everyone knows that a sequel rarely tops the original. A better description is Norma Desmonds line in Sunset Boulevard: she was not making a comeback; it was a return.

Let me start by thanking Michael OMalley, Mary Pasti, Niahm Cunningham, and Yale University Press for their support and confidence. I owe a special debt to Bruce Ackerman, Barry Friedman, John Hill, Rick Pildes, Mike Pitts, Tom Shakow, and Amanda Tyler for reading the draft manuscript and offering their thoughtful comments. Debra Denslaw and Kiyoshi Otsu provided vital assistance in gathering the photographs that help make the book come alive. The law journals that allowed me to reprint parts of my previously published work here, and whose officers edited those papers, also deserve my gratitude. The articles are Why Did the Incorporation of the Bill of Rights Fail in the Late Nineteenth Century? Minnesota Law Review 94 (2009): 102139, and Constitutional False Positives and the Populist Moment, Notre Dame Law Review 81 (2006): 821888.

Finally, I want to salute my colleagues at Indiana University School of Law-Indianapolis, whose friendship and encouragement is invaluable, and the scholars at the Roosevelt Study Center in Middelburg, The Netherlands, who hosted me during a delightful sabbatical when I ended up thinking a lot about this book, helped along by lots of herring.

INTRODUCTION

On Constitutional Failure

When you strike at a king, you must kill him.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

We learn more from failure than from success. Although this lesson is often a bitter one, everyone eventually learns its truth everyone, it seems, except constitutional lawyers. Their story of how We the People created, amended, and then interpreted the Constitution is an uplifting drama. The Founding Fathers and the miracle that was the Constitutional Convention, the abolition of slavery and Abraham Lincolns reconstruction of our ideals in the Gettysburg Address, Franklin D. Roosevelts development of the welfare state to overcome the Great Depression, and the Supreme Courts decisions striking down racial segregation are the pillars of modern legal analysis. Those achievements are clearly worth studying, but what about the close calls that ended in frustration? Their omission from the standard

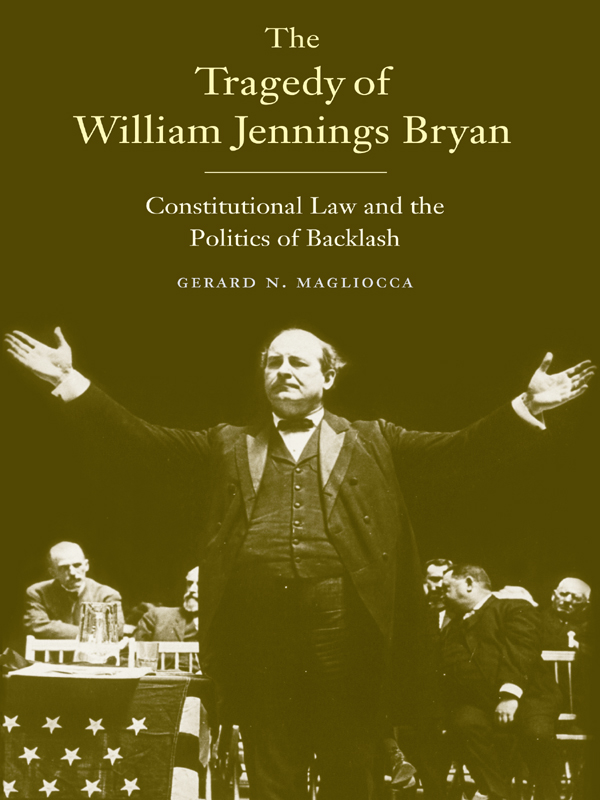

William Jennings Bryan, The Boy Orator of the Platte. Library of Congress.

The most important constitutional failure that is missing from the professional conversation is the defeat of the Populist Party and its presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, in 1896. Today Bryan is remembered mainly for his role in challenging the teaching of evolution in public schools during the infamous Scopes Trial. But in his heyday he was widely acclaimed as the nations greatest orator, and he carried the banner for liberalism in three presidential campaigns. Because he lost all three of those races (in 1896, 1900, and 1908) and was overshadowed by an even larger personality, we now associate progressive reform and, indeed, the entire political era with Theodore Roosevelt. Nevertheless, a central theme of this book is that Bryan, not the Rough Rider, was the greatest constitutional figure at the turn of the twentieth century.

The 1890s present a fascinating puzzle for political scientists. Bryans defeat in 1896 at the hands of William McKinley is commonly described as a realigning election that marked a major and long-lasting shift in public policy. Yet David Mayhew, a scholar at Yale, recently challenged this consensus by arguing that the 1896 result was not significant, in part because no dramatic legislative changes occurred after McKinleys victory.

A similar mystery surrounds constitutional law during the 1890s. Prior to that decade, the Supreme Court refused to hold that the Fourteenth Amendmentwhich guarantees the Just ten years later, compulsory segregation was the law, and African Americans in the old Confederacy were disenfranchised. On all of these questions, lawyers confront the equivalent of Planet Xa hidden force that exerts an observable pull. Since no constitutional amendments were ratified during the 1890s, what explains all of these dramatic changes?

The answer is that there was a powerful backlash against the protest movements associated with the Populists and their goals of wealth redistribution, nationalization of industry, and racial cooperation in the South. This fear spurred the political and legal establishment to fight back by increasing federal constitutional protection for property and contract rights, establishing Jim Crow to prevent an alliance between poor whites and African Americans in the South, and curbing civil liberties to ensure that Populist and labor activists could not rally support. There are many fine studies on the backlash phenomenon, but nobody has done an analysis of what may be the most significant constitutional backlash of all. This book takes up that challenge.

The idea that resistance is a powerful force that shapes the law was an important part of my first book.

By closely examining the backlash against Bryanism, I hope to dispel five misconceptions about the late nineteenth century. First, something important did occur as a result of the 1896 race, so the traditional view that that Bryan-McKinley Finally, the contraction of liberty that crippled so many of our citizens in this period was not inevitable. Millions marched and voted on behalf of a different vision during the 1890s, and their tale should be told.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso Z39.481992.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso Z39.481992.