ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

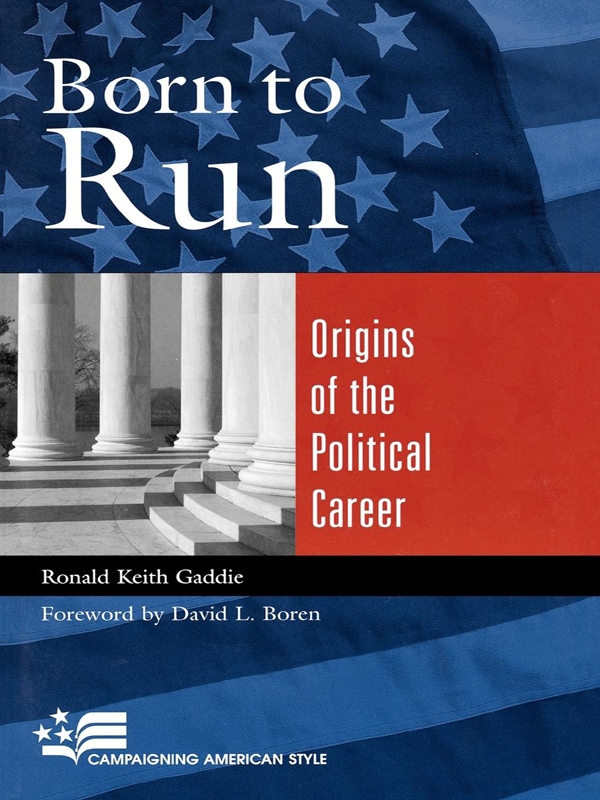

MARK TWAIN ONCE OBSERVED, There comes a time in every rightly constructed boys life when he has a raging desire to go somewhere and dig for hidden treasure. This book started in my mind in 1998, when Kenneth Corn called me up and said, Im running for the legislature. Then Shane Hunt called a day later and said the same thing. The tumblers turned in synch in my mind, screaming to me that this was the chance to go digging for the hidden treasure of what Joseph Schlesinger termed the hopes which lie in the hearts of young men and to see, up close, how political careers start and how political fortunes are built. Here before me was the chance to examine how young people become candidates and how as candidates with little in terms of resume or experience they start their careers and then build their political reputations.

For the next five years I met young candidates and legislators, observed their actions, and followed their progress. I bothered them with phone calls, tracked them in the papers and the media, and talked to political informants. Some of them I met as they first ran for office; others, just after they had won office. This book is about the rites of passage of nine people, from ambitious amateur to candidate, to lawmaker, and then in pursuit of higher ambitions. Not all of them initially succeeded. One grew weary of officeholding; two aspired to higher political callings. But all shared one trait: At a young age, these people stepped forward and said to their communities, Here I am. Make of me what you will. I will serve.

Instead of practicing political science at the hard edge of the desk, I was tromping through neighborhoods with candidates, traveling miles and miles from campaign event to campaign event, attending backroom meetings or getting drawn into debate prep. My frequent flyer cards are a bit fuller, and I put a lot of miles on my old Chevy Suburban. The travels turned into a rediscovery of the bits of democracy we forget about, like neighborhood fish fries, summer political party picnics, and visits with old folks and people in their homes. After the initial election trips, the study evolved from watching young politicians as a unique centerpiece on the campaign trail, to observing their socialization, their development of expertise, and their pursuit of power, influence, and reputation. Time on the campaign trail was traded for time in legislative offices and committee meetings, and then traded again for time on the campaign trail.

My first and greatest thanks must go to the nine people who are the foundation of this book: Matt Dollar, Shane Hunt, Joe Handrick, Adrian Smith, Thad Balkman, Stephanie Stuckey-Benfield, Michael V. Saxl, Kenneth Corn, and Jon Bruning. Their hospitality and accessibility over the past five years were crucial to telling this story, and I look forward to long conversations in the future.

All the folks who read bits and pieces of the book or who helped me prepare to visit their states deserve special thanks, including Sunil Ahuja, Hal Bass, Gary Copeland, Tony Corrado, Robert Cox, John Hibbing, Larry Hill, Malcolm Jewell, Cherie Maestas, Sarah Morehouse, and Brian Taylor. When the draft was complete, Chuck Bullock, Rhodes Cook, Richard Fenno, Ron Peters, Jos Raadschelders, and Joe Stewart read it from cover to cover and offered numerous comments and insightful suggestions that improved the manuscript. Robert Hogan at LSU was generous in sharing survey data from his study of state legislative candidate campaigns, and I am especially grateful for his assistance not only in sharing the data but in performing the data runs for the analysis interspersed throughout the book. A sabbatical from the University of Oklahoma allowed me back onto the campaign trail. My editor, Jennifer Knerr, took a chance on this book when it was half-written.

My spouse, Kim, and children, Collin, Alec, and Cassidy, endured my frequent absences, and I appreciate their love and support as I finished the book.

I want to make a last, personal observation about the road that led to this book and thank three people who showed me a road worth traveling. When I was an underperforming undergraduate at Florida State University, the best undergraduate teacher I ever saw, Glenn Parker, assigned a little orange and brown book titled Home Style in his course. I could not put it down. When I stubbornly insisted on going to graduate school, Glenn steered me to Chuck Bullock at the University of Georgia, who took me in, undisciplined and rough, and made a professional, and a friend, out of me. Then, there is Dick Fenno. After knowing his writings, I came to know him during the past decade. When I read Home Style for Glenns class, my reaction after finishing was That is what I want to do. And, finally, I am able to do so.

So this work is dedicated to Glenn, Chuck, and Dick, with thanks from a grateful student, and also to the memory of Senator Larry Dickerson (1956 2002), who lived the words of Appius Claudius: Every man is the artisan of his fortune.

Appendix

A Note on the Research Technique

THE STUDY OF POLITICAL AMBITION and political careers has its roots in probing, qualitative studies. Donald Matthewss (1954, 1960) classic studies of political leaders enumerate the attributes of legislators and note the role of sociological factors in determining opportunities to hold major office. It is the interviews and observations in his study that lent depth to our initial understanding of institutional ambition and institutional constraint on legislators. It has been field studies, such as those of Richard Fenno (1978, 1996,2000), Thomas Kazee and his contributors (1994; see also Kazee and Thornberry 1990), Sandy Maisel (1982), and Linda Fowler and Robert McClure (1989), that have proven most insightful in explaining how congressional candidates act on their ambitions. I adopted a field research technique combined with informal interviews, secondary source research, and supplemental survey data. Fenno (1996), in his Julian Rothbaum Lectures at the University of Oklahoma, published as Senators on the Campaign Trail , presents an eloquent rationale for the political scientist to get out of the office and onto the campaign trail:

Glimpses from the campaign trail ... remind us that it is, after all, flesh and blood individuals, real people we are talking about when we generalize about our politicians ... there is something to be gained by occasionally unpacking our analytical categories and our measures to take a first-hand look at the real live human beings subsumed within ... observation of politicians on the campaign trail is helpful because it takes us to the place where our representative form of government begins and endsto the home constituency. Representative government has local roots and a bottom-up logic. And that is precisely the perspective of the observational research that is conducted on the campaign trail. (6)

So political science benefits from studying politics in practice , rather than confining itself to the study of the residual of politics: political outcomes.

Problems arise from the use of the participant observation, especially when one enters a campaign for a small constituency. The most obvious problem that the researcher encounters is that he is part of the environment, part of the political experience. The voter, standing in her door, cannot help but notice who else is in the background. In the small-town and rural campaigns, rumors of outsiders can make their way through the political grapevine with great speed. As Fenno (1978) observes in Home Style , one key to effective participant observation is to blend into each situation as unobtrusively as possible (267). So you dress appropriately, assume the staff position, and stay out of the way.