To Our Children

Natalie and Thomas Logan Mayer

Rachel and Miriam Bernstein

Ross and Ryan Adkins

Katie, Daniel, and Elizabeth Busch

John, Andrea, and Kara Dukakis

Matthew Cornfield

Ava Brogi Lichter

Chapter 1

Why Are Presidential Nomination Races So Diffi cult to Forecast?

Wayne P. Steger, Andrew J. Dowdle, and Randall E. Adkins

The campaign for the 2012 Republican nomination is in full stride. Journalists, pundits, and bloggers offer analyses and speculations about which candidate will be the Republican nominee to face off against Barack Obama in the 2012 general election. But predicting the winner of the nomination campaign is more than a political spectator sport with entertainment value. Forecasting the winner tells us something about our understanding of the politics and processes of leadership selection in the United States. Forecast models are valuable diagnostic tools. Election forecasts generate an expectation for an outcome using theoretical arguments and empirical measures. If the outcome differs from the prediction, then the theory and/or the measures are wrong.

Above all, the accuracy or failure of a nomination forecast informs us about the locus of power in presidential nominations. To the extent that presidential nominations can be forecast with data from before the caucuses and primaries, we can infer that the critical period of the campaign occurs prior to rather than during the primaries. In that case, the caucuses and primaries would merely confirm the results of the campaign that occurs before the primaries. If predictions using data from prior to the delegate selection season are inaccurate, while predictions incorporating the results of caucuses and primaries are closer to the mark, then the caucuses and primaries would appear to have an independent influence on the nomination. In this scenario, caucus and primary voters could be said to have relatively greater power or influence on the selection of the presidential nominees.

Beyond this macro-level picture, nomination forecasts inform us about which elements of a campaign are critical in presidential nominations. For example, Mayer demonstrated that a candidates standing in preprimary national opinion polls is a powerful predictor of which candidate will win the nomination. In short, nomination forecasts are more than just speculations about who will win or lose a campaign. The task of predicting a winner is a tool that can be used to understand presidential nominations.

ELECTION FORECASTING: AN INTRODUCTION

All forecasting models are premised on the idea that we can predict the outcome of an event using information from a time period prior to that event. Economic forecasts, to take the best known example, take data about current economic conditionsnew housing starts, factory inventories, changes in the money supplyand, if they work, use those data to predict what the economy will look like three, six, or twelve months in the future.

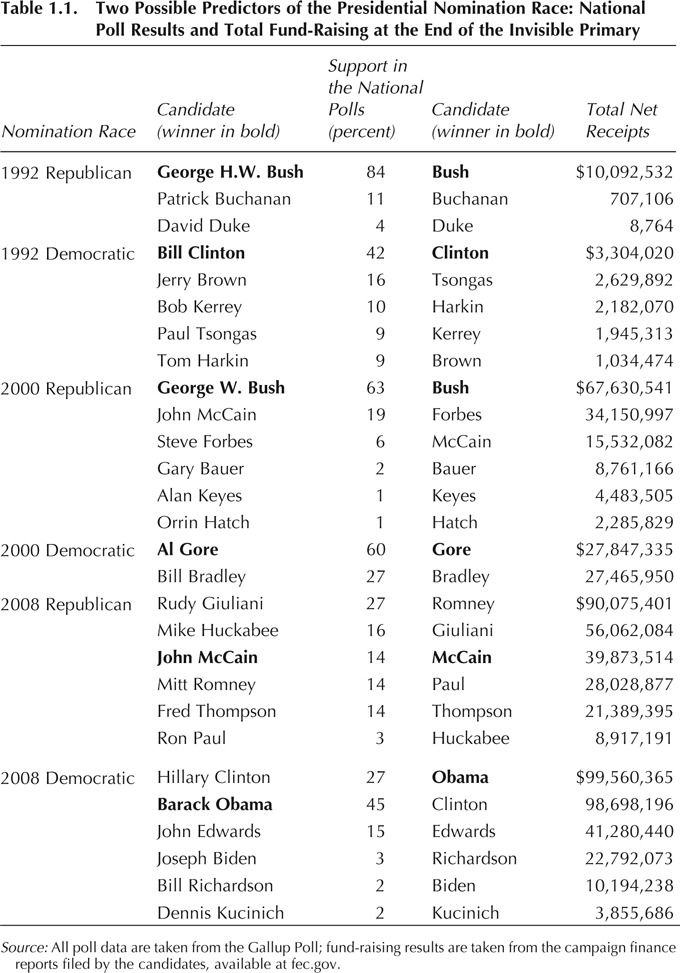

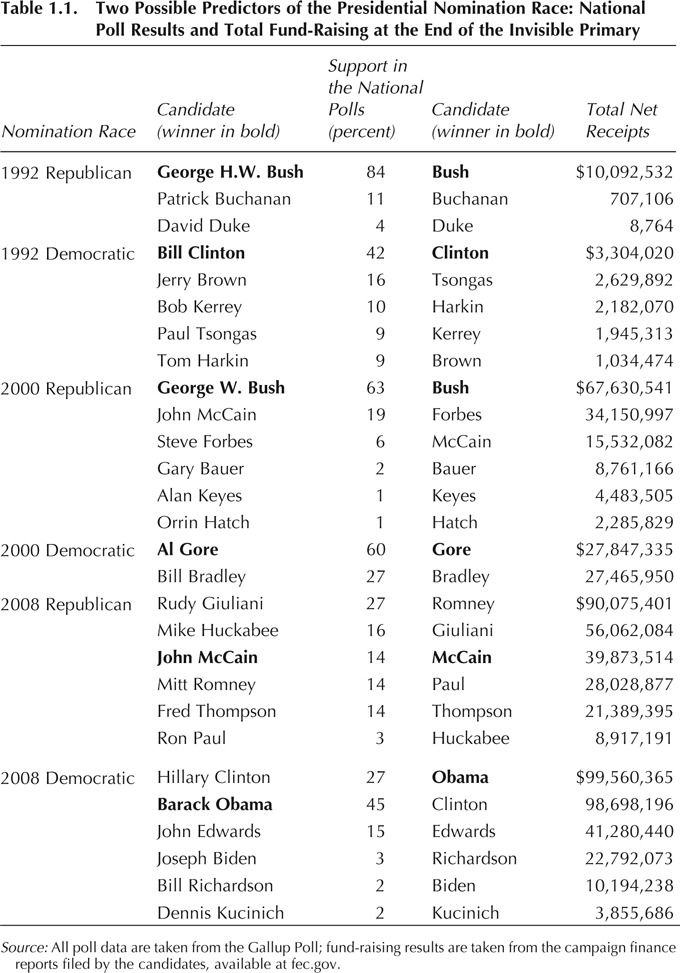

Election forecasting, at least as a scholarly endeavor, began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when a number of political scientists and economists argued that certain factors could be used to predict how elections (presidential and congressional) would turn out months before the votes were actually cast. In the 1990s, the same logic and set of statistical methods was extended to presidential nomination races. Consider, for example, the first column of data in Table 1.1. For at least a year before the first delegates are selected, national pollsters frequently ask ordinary Americans which party they belong to and then, depending on the answer, ask them which candidate they would be most likely to support for their partys next presidential nomination. In Table 1.1, we report the results from 1992, 2000, and 2008 of the last survey that the Gallup Poll took before the start of the delegate selection seasonthat is to say, the last poll before the Iowa caucuses. [The results for all years since 1980 are presented in the Appendix to this book.] In the first four races shown herethe Democratic and Republican races of 1992 and 2000the candidate leading in the last national poll went on to win the nomination. In 2008, by contrast, the final preseason poll was less helpful. The poll leaders were Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton, but the nominations went to John McCain and Barack Obama.

The second column of data in Table 1.1 shows another variable that might plausibly be used to forecast presidential nomination races: how much money each candidate had raised in the year before the election year (e.g., in the 2008 race, how much the candidates had raised in 2007). At first glance, these data seem to predict the winner in five of the six races shown in this table. As we will see, however, almost all scholars have found this to be a spurious relationship. It works because popular candidates also tend to be successful fund-raisers; but once a candidates standing in the polls is taken into account, the fund-raising totals add nothing to the accuracy of our forecasts.

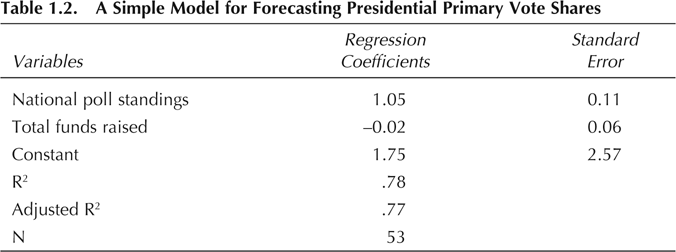

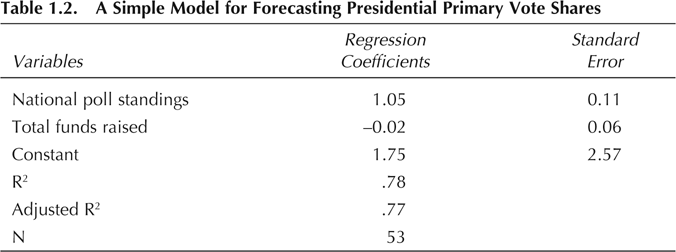

Can we be more precise about the effect of these or any other variables on the outcome of a contested nomination race? The final step in election forecasting is to take the sort of data shown in Table 1.1 and enter them into a regression equation, a statistical technique that enables us to generate a numerical prediction about the vote that each candidate will receive in all of his or her partys presidential primaries. An example is shown in Table 1.2. In general, according to this equation, every additional percentage point of support a candidate received in the national preprimary polls translated into 1.05 percentage points in the total primary vote. By contrast, as already noted, once poll standings are held constant, preseason fund-raising has no effect on the primary vote.

General elections forecasts are based on factors known to affect the two-party popular vote, such as the incumbent presidents popularity, measures of economic conditions, and the relative strengths of the political parties. Such indicators are not much use in forecasting presidential nominations, however, since these factors affect voters choices between the political parties rather than among candidates of the same party. The next section discusses presidential primary vote forecasts, with special attention to those factors that have been found to be significant predictors of nomination outcomes. The latter part of the chapter analyzes why presidential nominations are difficult to forecast and why nomination forecasts generally have more error than general election forecasts.

PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION FORECASTING: A REVIEW

Forecasts of the presidential primary vote implicitly assume that the critical period in the presidential nomination process occurs before the primaries.

Presidential primary forecasts typically begin with the 1980 election. Presidential nominations prior to 1972 were largely determined by party organizations, which selected national convention delegates through party-run caucuses and state conventions. Most states did not hold presidential primaries, and many that did have primaries did not actually use the presidential preference vote to select or bind the delegates.