BLACK WIND, WHITE SNOW

Charles Clover is an award-winning journalist currently based in Tokyo, where he writes for the Financial Times and Nikkei Asian Review. He was previously the China correspondent and the Moscow bureau chief for the Financial Times.

Further praise for Black Wind, White Snow:

[A] deeply researched, fascinating account of how nationalist views that were once dissident or marginal in the Soviet Union seeped into the corridors of power in the Kremlin when Marxism-Leninism stopped working Clovers book deserves to win prizes for originality of mind. Michael Burleigh, The Times

An important contribution to this discussion Mr. Clovers reporting is excellent. The Economist

The new Russian nationalism for which Dugin speaks is entirely genuine. Clover casts a considerable light on its roots. Rodric Braithwaite, Open Russia

Clear-sighted and sceptical However frightening the message, one wants to read on to the last whistle. Brian Morton, Glasgow Herald

Absorbing and often disconcerting The story of the evolution of a strain of Russian political thought barely known in the West over the last hundred years. Andrew Stuttaford, Weekly Standard

Clover offers a thoughtful and well-contextualized account of a potent form of Russian nationalism. Lucien Frary, Terrorism and Political Violence

Clover traces the development and evolution of Eurasian ideology, while simultaneously pointing out that its central tenets have been discredited intellectually since their establishment Painstakingly relates the life stories and intellectual struggles of largely forgotten thinkers. Eric Green, Foreign Service Journal

Copyright 2016 Charles Clover

Preface to the new edition copyright 2022 Charles Clover

First published in paperback in 2017

New edition paperback published in 2022

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

All reasonable efforts have been made to provide accurate sources for all images that appear in this book. Any discrepancies or omissions will be rectified in future editions.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Typeset in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022939139

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-300-22645-4 (pbk)

ISBN 978-0-300-26835-5 (new edn pbk)

e-ISBN 978-0-300-26925-3

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Rachel and Jaya

Now I held in my hands a vast methodical fragment of an unknown planets entire history, with its architecture and its playing cards, with the dread of its mythologies and the murmur of its languages, with its emperors and its seas, with its minerals and its birds and its fish, with its algebra and its fire...

Jorge Luis Borges

CONTENTS

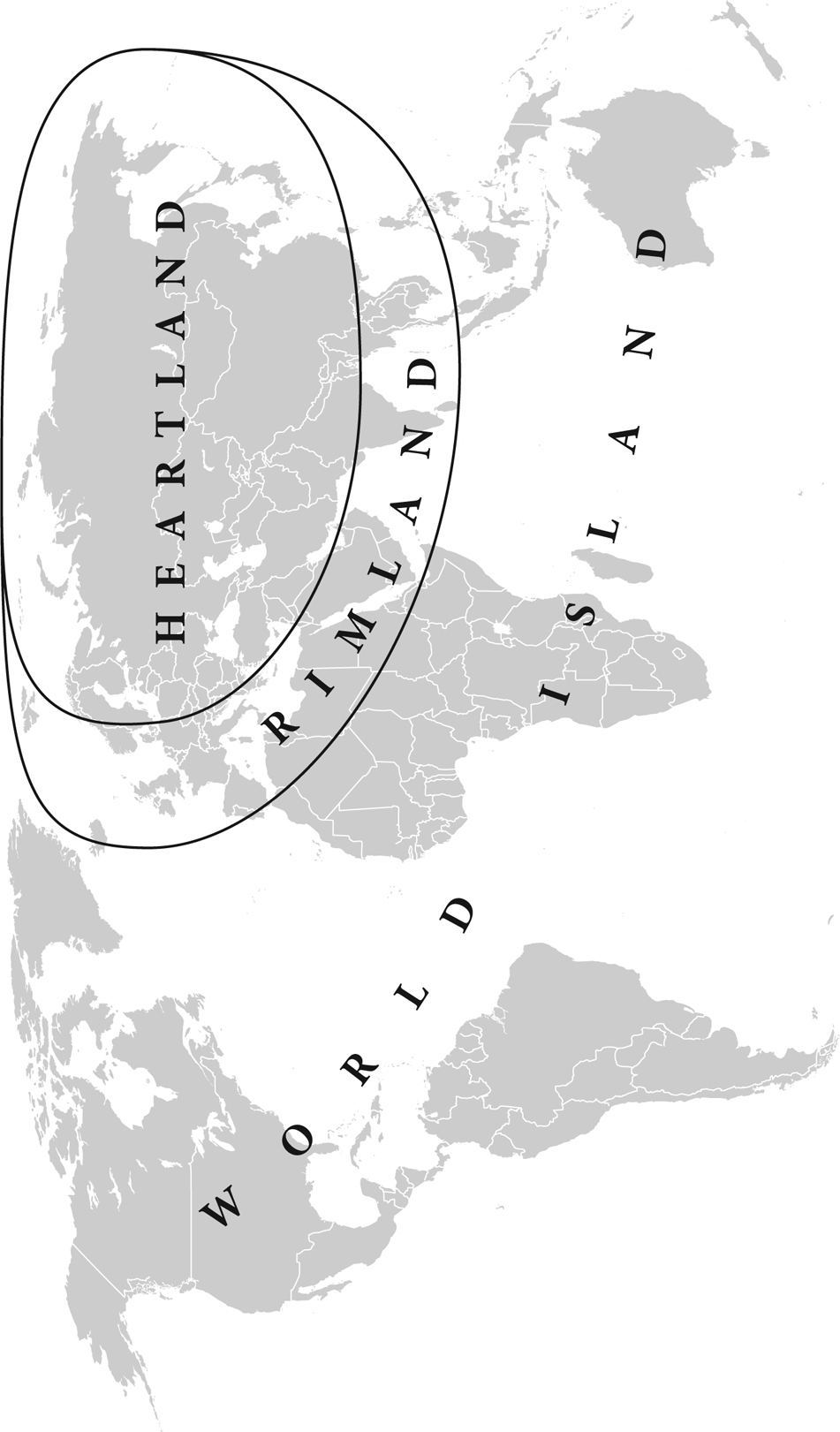

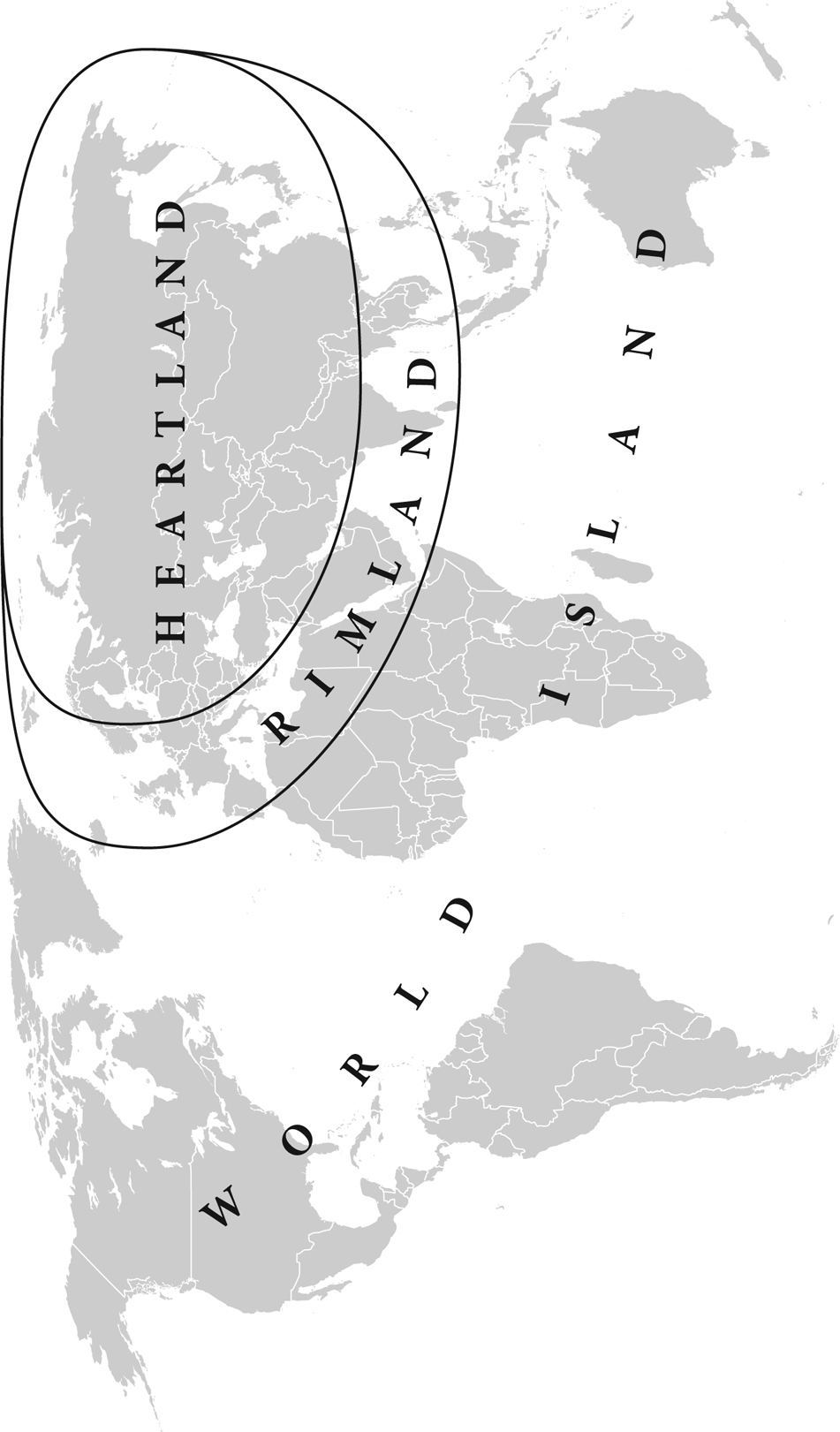

Map of Eurasia, first outlined by Sir Halford Mackinder in his The Geographical Pivot of History, and reproduced in Russian by Alexander Dugin in The Foundations of Geopolitics (1997).

PREFACE TO THE NEW EDITION

E astern Europe has long been the anvil on which new versions of the global order are forged. From Sarajevo to Munich to the Molotov Ribbentrop Pact; from the Yalta agreement to the end of the Warsaw Pact and the expansion of NATO, all new paradigms in a century of international relations have been defined inside the triangle delineated by the Baltic, Adriatic and Azov seas.

This curious historical pattern would appear to vindicate one of the most overused dictums in the study of international affairs: Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland, said geographer Halford Mackinder in 1919. Whoever rules the Heartland will rule the World Island, and whoever rules the World Island will rule the world.

Mackinders thesis, now almost a clich, demonstrates the curious interaction between ideas of empire and the bloody events that create and destroy them. He was predicting the inevitable centrality of Eastern Europe to any great power designs it stood between Russia (the Heartland) and the domination of the rest of Eurasia (the World Island), according to him. Some pages in this book are devoted to the use to which Mackinders words were put in Russia as it started down its present tragic path.

The most recent version of the international order what we know as the postwar liberal order may have ended on 24 February 2022. In one night of cruise missile strikes on Ukraine, followed by an invasion of a fearsome armada of tanks, aircraft and 200,000 troops, Russia single-handedly turned the clock back to a time many people thought they had left behind.

The bloody and heartbreaking events in Ukraine highlight the role played by all manner of theories, ideas, and alternate realities in political life. This is clear to see just from watching Vladimir Putins rambling speeches.

However the Ukraine crisis ends, Russia will have forever changed the nature of global politics. As I write this the Russian army is bogged down and taking heavy casualties. Whether this is the end of the war or the midpoint in a multi-year or multi-decade effort that began with the taking of Crimea in 2014 is unclear. It could just as easily presage the end of the Putin regime and possibly of the Russian Federation as we know it.

When I first published this book in 2016, this new world was already on the horizon. Liberal democracy was in retreat, from Hungary to Turkey to the Philippines. Authoritarian powers were flexing muscles: Russia in Syria and Donbass, China in the South China Sea and Taiwan.

The first edition of this book outlined what appeared to be a very fanciful literary-historical project to create a new imperial nationalism in Russia on the ashes of the former USSR, reclaim parts of Russias imperial greatness and create an alliance system aimed at confronting US hegemony in Eurasia.

Today, that project, known as Eurasia or Eurasianism, seems a little closer to reality. Putins regime has shown it is not just a kleptocracy but has a motivating ideology in which, even if it was in part constructed for instrumental reasons, many in the Kremlin now truly believe. The Kremlin has shown a willingness to sacrifice untold billions in foregone economic future to a goal dreamt up by some writers who just a few years ago were marginalized as barking mad.

Meanwhile, to the above list of era-defining conspiracies aimed at dividing Eastern Europe must be added a new event that took place on 4 February 2022, in Beijing, where Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin signed a 5,000-word pledge of a no limits partnership on the eve of the Olympics. It was partly a non-aggression pact, and partly a MolotovRibbentrop-style division of Eurasia into spheres of influence.

The emergence of Eurasia as a global anti-western coalition of revisionist states seems a bit less fanciful than it did when this book was first published in 2016.

In such a post-liberal world, power counts for more than principle. But this book argues that power is not everything and that theories and ideas, even if utterly irrational from our perspective, count for a lot. A formerly pragmatic leadership who saw nationalism as useful for domestic public opinion management now sees Russias destiny in the same terms as marginal pamphleteers, who have begun wagging the dog.

Next page