Charles Clover

REWILDING THE SEA

How to Save Our Oceans

EBURY

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Ebury is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in the United Kingdom by Witness Books in 2022

Copyright Charles Clover, 2022

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Front Cover Design Dan Mogford

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and, if notified of any corrections, will make suitable acknowledgement in future reprints or editions of this book.

Maps and illustrations Emily Faccini 2022

Epigraph on Ian Tyson, reproduced with permission

ISBN: 978-1-473-59846-1

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Dave Sales, 19372022, and to those like him who have opted to fish less in order to have more.

Introduction

Return of the Giants

Four strong winds that blow lonely

Seven seas that run high

All those things that dont change, come what may

Ian Tyson, Four Strong Winds, 1961

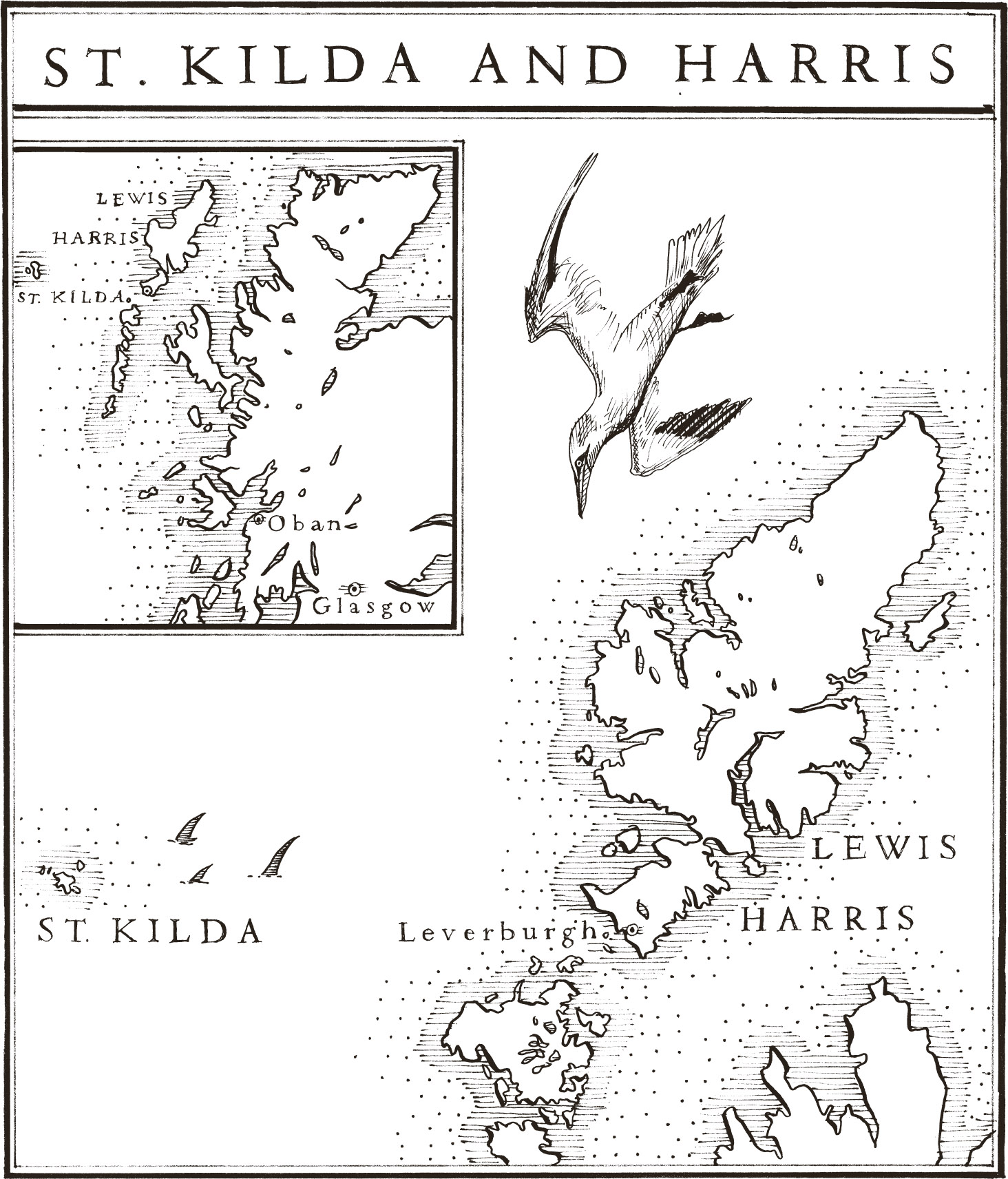

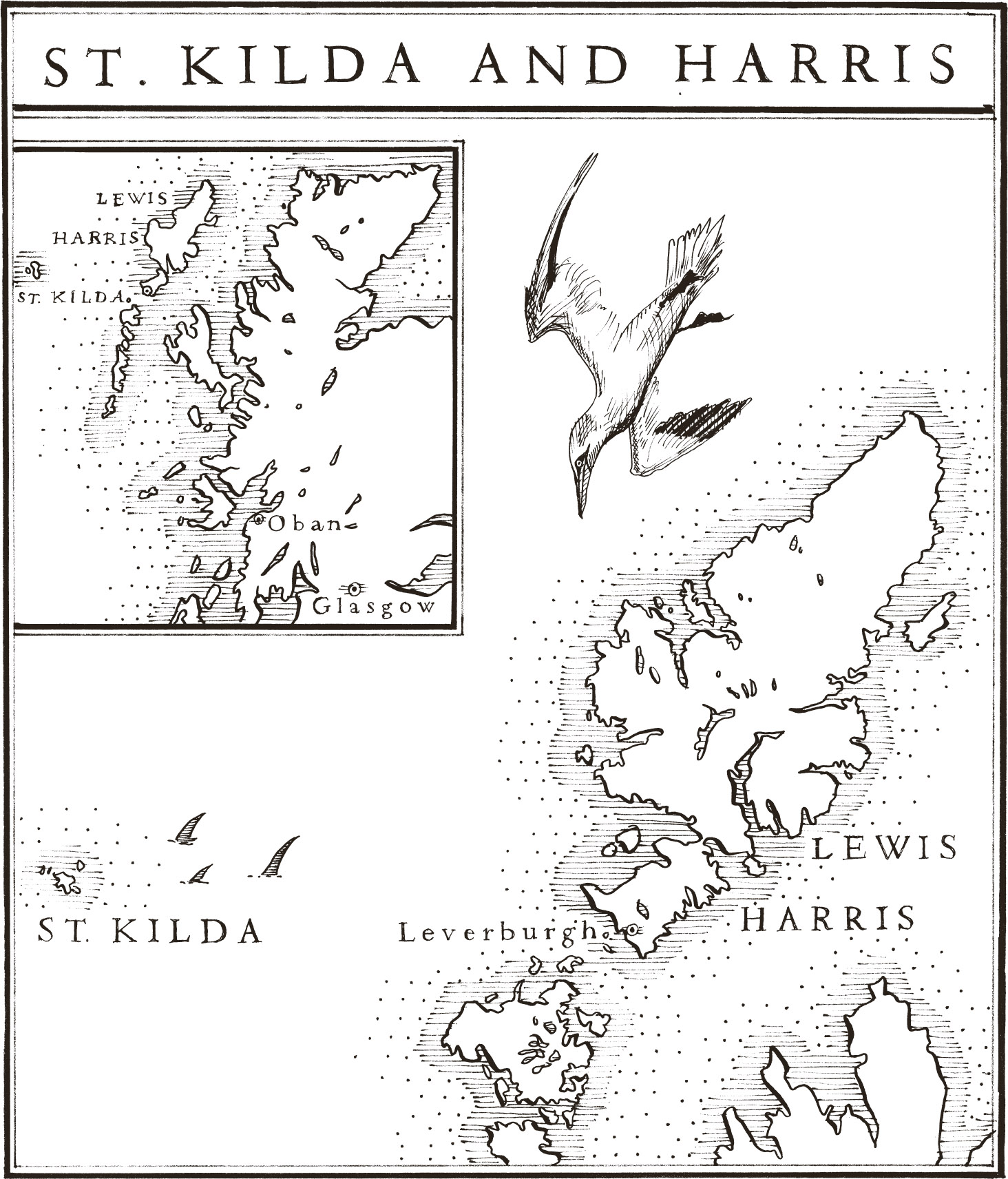

The day of Tom Hortons first encounter with the creature he was looking for was misty and overcast with not a breath of wind. The sea off the west of Scotland was oil-slick calm, moved only by a slight swell from far out in the Atlantic. Tom had motored out 40 miles to the remote islands of St Kilda from the village of Leverburgh, on the Isle of Harris, on Angus Campbells catamaran, the Orca 3. It was September 2014 and they were on a mission to find and tag a bluefin tuna, a year after Angus had first spotted the shoals, prepared a squid lure and caught one weighing 515lbs, a Scottish record. Bluefin had not been seen in any numbers in this part of the north-east Atlantic for decades. Angus was the first to spot them and work out how to catch one. Marine Scotland, part of the Scottish government, then decided to record what was happening and recruited Tom as a volunteer.

The day had already been memorable for wildlife spotting. As Tom and Angus started out, they saw a pod of around 200 dolphins, far off. Then, on the journey between the Isle of Harris and St Kilda, a juvenile male minke whale circled their boat. They also sighted a sei whale as it rolled in the distance and a leatherback turtle lazing at the surface close by. As Tom said, it was a day when you felt something big was about to happen.

They were motoring back towards Harris, around two oclock, out of sight of land, when Angus said: This is what we are looking for.

Coming into view was a maelstrom of bird activity gannets mostly but also bonxies (great skuas), sooty shearwaters, Manx shearwaters and storm petrels milling around. The gannets were diving into shoals of fish while the shearwaters darted between picking scraps off the surface. The bonxies were being their usual nuisance to the other birds. The water was so clear that you could see the birds swimming below the surface. The sea was glistening with slowly sinking silvery scales from the baitfish that had been forced to the surface by predators beneath, only to be picked off by the birds. Tom spotted numerous minke whales foraging on the shoals of baitfish.

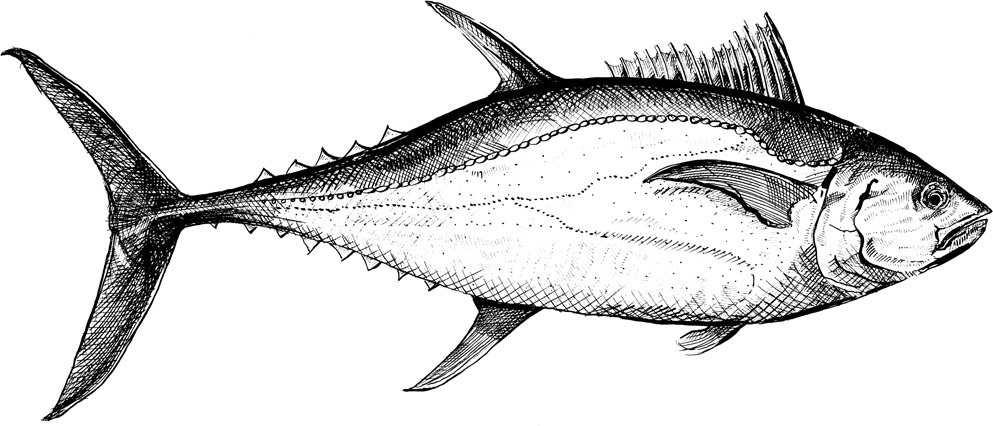

Angus was certain there were bluefin present. Tom thought he was mistaken. Then, out of nowhere, a shoal popped up right in front of the boat. At first there were welts in the water and dorsal fins visible above the silvery surface. Then two large tuna surfaced five metres in front of the boat and dived back down underneath it, close enough for Tom to get four pictures that proved without doubt what they were seeing was bluefin. It all happened so quickly. The gannets were calling, the sooty shearwaters were whooshing, then the boat was through the feeding frenzy and the fish had moved on.

Tom and Angus were privileged to gain a glimpse of the part predators play in a fully functioning ecosystem, a sight unfamiliar until the wild and dynamic element of a bluefin shoal returned to northern seas. The tuna rounded up their prey of small fish probably whitebait or herring fry into tight shoals or balls and pushed these up to the surface. This provided a feeding bonanza for birds that cannot dive for fish, such as the petrels and the skuas which just steal prey from others. The petrels and skuas are rare now, rarer than when there were more large predators in the ocean, and so it is true to say that the bluefin are breathing life back into the whole system. In a real but unquantifiable way, they have rewilded it.

Seven years later and Tom has logged over 2,000 sightings of bluefin shoals in UK and Irish waters, in the Hebrides, in the Celtic Sea and off Falmouth. He is based at Exeter Universitys campus at Falmouth in Cornwall and the paper of which he is the lead author records with authority that Atlantic bluefin tuna returned to the English Channel from 2014 onwards, seasonally between August and December, after a prolonged absence.

The Atlantic migrants had not been seen in UK waters since shoals of giant tunny fish, as they were then called, preyed on herring in the North Sea off Scarborough in the 1920s and 1930s. These giant fish of 800lb or more were pursued by big-game fishermen from high society and film stars such as John Wayne, Errol Flynn and David Niven. The huge North Sea herring shoals that lured them there have since gone but there is plenty of sardine and anchovy in the warming waters of the English Channel and right out to the edge of the continental shelf to attract the foraging tuna. Now there are days in the Channel and the Celtic Sea, says Tom, where everywhere you look theres a bluefin.

The giants have returned. Why have these emperors among fish, their flesh so highly prized for sushi and sashimi in Japan and the Far East, surged back into north European waters after so many decades of plummeting towards extinction? Scientists say that several factors may be involved: the changing climate, the abundance of prey and the most likely overall explanation for the bluefins expansion northwards the growing size of the population. Creatures expand their range when there are more of them that is a well-established pattern in ecology. The bluefin fits that pattern. This means that the crucial factor in the bluefins return is the decision by Atlantic, Mediterranean and Far Eastern nations to stop overfishing the species and to crack down on illegal fishing in a series of steps from 2010. This stands out as one of the great conservation achievements of this century.