AMERICAN BUSINESS,

POLITICS, AND SOCIETY

Series Editors:

Richard R. John, Pamela Walker Laird, and Mark H. Rose

Books in the series American Business, Politics, and Society explore

the relationships over time between governmental institutions and

the creation and performance of markets, firms, and industries

large and small. The central theme of this series is that public

policyunderstood broadly to embrace not only lawmaking but

also the structuring presence of governmental institutionshas

been fundamental to the evolution of American business from the

colonial era to the present. The series aims to explore, in particular,

developments that have enduring consequences.

A complete list of books in the series

is available from the publisher.

Copyright 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used

for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this

book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission

from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

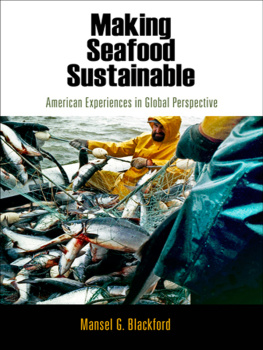

Blackford, Mansel G., 1944

Making seafood sustainable : American experiences in global perspective /

Mansel G. Blackford. 1st ed.

p. cm. (American business, politics, and society)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4393-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Sustainable aquacultureUnited States. 2. Fishery policyUnited

3. Fishery managementUnited States. I. Title. II. Series: American business, politics, and society.

SH136.S88B53 2012

639.8dc23 2011032477

PREFACE

Born in 1944, I remember clearly the excitement and relief that ran through members of my family on a cold, winter evening in 1952. Then a young boy growing up in a pre-Starbucks Seattle, I was delighted that my father, who pioneered in the development of Alaska's king-crab fishery as the captain of the Deep Sea, a combined catcher-processing vessel, was home for several weeks. That night he received a telephone call from a friend, who was the master of another fishing boat that had also just returned to Seattle from Alaskan seas. He told my father that water had entered one of his ship's cold-storage holds, partially flooding it and encasing the halibut there in ice. My father could have one of the fish, if he would come down to the vessel and chip it out. Times were tough, and my father was happy to do so. In the early morning, helped by a friend, he brought home a frozen 150-pound halibut. Fortunately, my family had a horizontal freezer large enough to receive the fish. For weeks, along with other family members, I ate halibut prepared in every conceivable mannerboiled, baked, fried, poached, broiled, and creamed. We also ate king crabs, for which a market was just being developed, from my father's vessel, until we could hardly face another dish of them. Meat was a rare treat, indeed, in those years. However, members of my family were unusual in their dining habits.

At the time, seafood such as king crabs and halibut did not reach the tables of most Americans, especially if they lived in inland cities. In many parts of the United States, seafood consisted of canned salmon and canned tuna fish. Processing seafood by freezing was in its infancy. Fresh fish was sold in grocery stores and restaurants mainly in coastal cities such as Seattle, San Francisco, Boston, and New York. Today, technological advances, such as jet airplanes and new freezing techniques, have made it possible for processors and distributors to offer people throughout the United States and in other nations a wide variety of seafood. Fresh, wild salmon from Alaska nestle next to frozen, farm-raised tilapia from China in grocers' counters across America.

My book explains how this transformation occurred. To do so, I explore the interactions among fishers, executives of seafood-processing firms, governmental officials, scientists, and environmentalists in formulating policies that created the food chains connecting boats to consumers.

Though many variables, from rising water temperatures to changes in marketing methods, have shaped the modern seafood industry in the United States and abroad, evolving governmental policies have been at the heart of the alterations. My book is, at its core, about governmental regulation of business and its ramifications. State and federal government oversight was the chosen path to make fishing sustainable. My study reveals that regulatory regimes for seafood have changed dramatically over the past four decades. My work analyzes especially how, during the past generation, new regulations and their implementation have created sustainable fishing for many types of seafood in the Northeast Pacific, a marked contrast to over-fishing, which has continued to devastate many of the world's commercial fisheries, including some in American waters, such as the New England cod fishery.

Congressional legislation has been crucial to this process. Passed in 1976, the Fishery Conservation and Management Act sought to protect American fishers from the onslaughts of their foreign counterparts by excluding foreigners from fishing within 200 miles of the American shores. That same legislation made possible sustainable fishing by requiring that fishers harvest no more fish than could be replaced by natural reproduction each year. Leading seafood types of the Northeast Pacificincluding salmon, king crab, and some bottom fish (such as Pacific cod, halibut, and pollock)were at various times over-fished. However, new types of governmental regulation eventually limited the overall catches of many species and pulled them back from the brink of commercial extinction. My volume looks at how business leaders and government policy makers crafted and implemented this legislation.

Working on the topic of over-fishing has continued and expanded my long-term interest in the history of American politics and the nation's political economy. As I came of age in Seattle during the 1950s and early 1960s, I visited Alaska on several occasions. No doubt, my father's participation in king crabbing helped spur my interest in the history of fisheries. I attended college and graduate school on the Pacific Coast, in Seattle and Northern California during the 1960s and early 1970s. In the 1980s, I spent two years living with my family in southern Japan, where I taught in Fukuoka and Hiroshima as a Fulbright Lecturer. Travelling throughout Japan, I had many opportunities to talk with local fishers and was able to go out on the boats of several of them. Flying to and from Japan, I stopped over in the Hawaiian Islands. During the 1990s, moreover, I taught on Maui on several occasions for the University of Hawaii, experiences that brought me into close contact with a broad range of Pacific Islanders, including fishers.

My professional work has allowed me to combine interests in business and environmental history, together with abiding concerns for the histories of the American West and the Pacific. Many of my books have explored intersections in these fields, as does this one. I have long been concerned in my research and teaching about connections among business changes, alterations in physical and social environments, and the development of government policy. My works have emphasized the complexity of political decision making and have stressed that most decisions have been compromises resulting from the inputs of numerous groups of stakeholders, ranging from politicians to business people to environmentalists and to indigenous peoples. However, my research on the topic suggests that workable solutions to difficult problems were possible in open political systems in which members of different groups had at least some trust in each other and in which they shared basic assumptions about the parameters of feasible actions.