The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

For Hal

Only connect! Live in fragments no longer.

E. M. F ORSTER

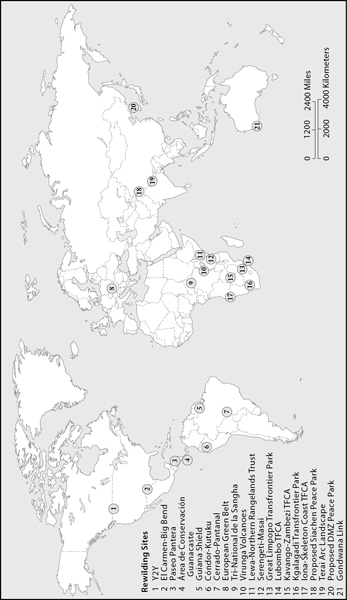

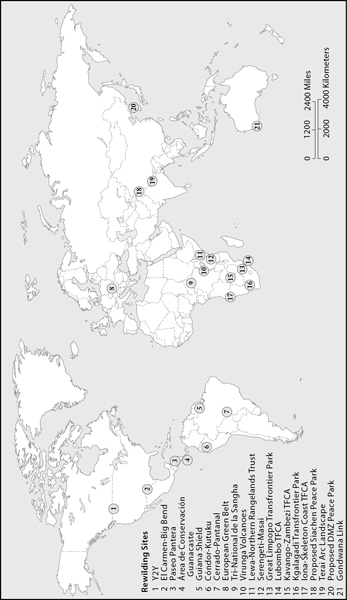

Global Map: A sampling of hundreds of rewilding projects around the world involving every large-scale method from transboundary and community conservation to ecological restoration.

INTRODUCTION

THE PREDICTA MOTH

Over the years, coyotes ate many of Michael Souls cats. For most people, this might have been the end of the story, a nasty reminder of natures darker proclivities. But Michael Soul is not most people.

Soul is a biologist. At the time, he was a professor at the University of California at San Diego, living in the chaparral canyons outside the city. He had grown up in the canyons, poking around in the leaf litter, catching lizards. When the boy became a biologist, he recognized that the chaparral was a unique ecosystem, with its own suite of interdependent plants and animals, the coastal sage scrub home to fox and bobcats, wrentits and spotted towhees, cactus mouse and California quail. But to real estate developers, the canyons were empty wasteland, waiting to be turned into homes. As he watched the progressive paving of the canyons, Soul found himself even more distressed about the big picture, the loss of the ecosystem, than about the cats. Recent breakthroughs in biology had suggested that fragmentation of habitat inevitably threatened species. As developers carved the canyons into suburban lots, leaving behind islands of isolated brush, Soul was alarmed enough to investigate that theory, and he sent students to compile data on the disappearance of birds from thirty-seven forlorn chaparral islands. He also had them collect data on local carnivores, to see if predation was a factor. After two years, as expected, data showed that the number of birds and other species in each patch was diminishing.

But the data revealed something else, something counterintuitive. In canyons with coyotes, a greater diversity of birds survived. Canyons without coyotes supported fewer species. Having seen ample evidence that coyotes were responsible for his disappearing petscats flying through the cat door as if chased by the devilSoul had a theory: more coyotes meant fewer cats. Another study confirmed it: one in five coyote scats contained domestic cat.

Before long, scientists were realizing that much of the country was suffering from a bad case of mesopredator release. The artificial absence of wolves and other large predators gave cats, dogs, raccoons, and foxes license to grow fat on wild birds from the beaches to the mountainsides. Soul had observed just one manifestation of a crucial new scientific discovery: predators do not merely control prey. They control other predators, and by doing so, they regulate species with which they never directly interact. They regulate biological processes down the food chain. As scientists study the unbalanced and fragmented systems humans create as they alter the environment, they are realizing how interdependent species are. In a way, all of us are now living in a scientific experiment similar to that which San Diego developers created by carving up the canyons. We have unleashed forces we are still struggling to comprehend.

This global experiment is comparable to the one Americans unwittingly set in motion in the 1950s by sowing the land with toxic pesticides. In the fable that opens Silent Spring , Rachel Carson described a strange blight settling over a town. Carson helped keep that pall from settling over the whole country by inciting a national debate that led to the banning of DDT.

But the shadow has fallen again. This time the problem is neither as concentrated nor as easily tackled as that of pesticides or pollution. This time the problem is the disappearance of nature itself.

* * *

The blight we are now experiencing, termed the demographic winter, is a result of human population growth, rampant development, and the destruction of ecosystems.

Biodiversity loss is now lining up to be the greatest man-made crisis the world has ever known. Biologists call it the Sixth Great Extinction, or the Holocene extinction event, after our current geologic time period. (The five previous extinction events all came before the evolution of Homo sapiens , apparently triggered by a cataclysmic event or combination of events, such as a fall in sea level, an asteroid impact, volcanic activity.) Mass extinctions are different in kind from what specialists term background extinctions, the rare but regular loss of between one to ten species per decade. Two hundred and fifty million years ago, the most catastrophic, the Great Dying of the Permian age, wiped out over 90 percent of all species in the oceans and 70 percent on land. It took tens of millions of years for life to recover.

The current extinction rates are alarming enough. Preeminent biologist E. O. Wilson believes we stand to lose half of all species by the end of this century. Conservative estimates suggest that the extinction rate in the modern era has reached a hundred to a thousand times normal.

Climate change further exacerbates biodiversity loss, and each of these crises magnifies and intensifies the effects of the other. As the planet warms and dries in some areas, species are pushed out of niches they currently occupy. Some of them, including the emperor penguin in Antarctica and the polar bear in the Arctic, have nowhere to go. Worldwide, as water temperatures rise and ponds dry, exposing amphibians and their eggs to ultraviolet radiation and disease, a third of those species are threatened with extinction. As people burn forests for agriculture and grazing, as they replace native vegetation with monoculture crops that discourage cloud formation, they alter the dynamic relationship between the earths surface and the atmosphere, initiating further drying and warming, and further species loss.

Why do species matter? Why worry if some go missing? Part of the answer lies in the relationships coming to light between creatures like the canyon coyotes and the chaparral birds. After the nineteenth centurys great age of biological collecting, when collectors filled museums to bursting with stuffed birds and pinned beetles, the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have proved to be an age of connecting . Biologists have begun to understand that nature is a chain of dominoes: If you pull one piece out, the whole thing falls down. Lose the animals, lose the ecosystems. Lose the ecosystems, game over.

Put another way, in this era of connection, we have learned that everything is interdependent. There are no spare parts. Predators regulate a constellation of other predators and prey; grazing animals regulate grasslands; grasslands and forests regulate climate. The physical world is like a big organic machine, an old car, for example, composed of interconnecting moving parts. Eco systems . You can lose inessential cosmetic elements, the bumper, the hubcaps, and it will still run, for a while. But eventually, if you lose enough critical parts, the machine will fail. When parts of an ecosystem are lostpredators, grazers, pollinatorsthe machine starts stalling, stuttering, failing. The processes of life grind to a halt.