A S MALL N ATION of P EOPLE

W. E. B. D U B OIS AND A FRICAN A MERICAN P ORTRAITS OF P ROGRESS

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

with essays by

David Levering Lewis and Deborah Willis

an honest, straightforward exhibit of a

small nation of people, picturing their life and development

without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.

- W. E. B. DU BOIS

T he true test of the progress of a people is to be found in their literature, Daniel Alexander Payne Murray, the Assistant Librarian of Congress, wrote more than one hundred years ago. His untiring efforts to compile a collection of works by African Americans, which would otherwise have been lost, vastly enriched the holdings of the nations Library. Among the treasures Murray brought to the Library of Congress were books, pamphlets, and photographs displayed as part of the American Negro Exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition. Murray collaborated with Thomas Calloway, a lawyer, educator, and organizer of the exhibit, and W. E. B. Du Bois, then a sociology professor at Atlanta University, who concentrated on a study of Georgia, to assemble this compelling testament to the accomplishments of black Americans since Emancipation.

The American Negro Exhibit included some five hundred photographs of people, homes, churches, businesses, and landscapes that captured the lives and communities of African Americans at the turn of the twentieth century. One hundred and fifty of these photos are featured in this book. Although a few have been published before, this is the first time that a significant number of these images are brought together in a single volume. The essays by noted scholars David Levering Lewis and Deborah Willis shed new light on pivotal events in American history and the history of black photography that provide the context for the choice of these photographs in 1900 and their importance today.

The Paris Expostrion photographs form part of Murrays legacy to the Library of Congress, an institution he served for fifty-two years. Bom to freed slaves, he had little formal education when he became a personal assistant to Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Spofford in 1871. He soon mastered several foreign languages and was a remarkable researcher. These skills led to his appointment as Assistant Librarian in just ten years icated himself to searching for works by black authors and compiling an impressive bibliography. He built the Librarys collection of books and other written materials demonstrating the achievements of African Americans. At his death in 1925, he also bequeathed his personal library of nearly fifteen hundred volumes to the Library. In his life and work, Daniel Murray embodied the spirit of the institution he loved as a seeker and disseminator of knowledge.

Today the Library of Congress-which holds more than 126 million items, most of them housed in three buildings on Capitol Hill-continues to serve the legislators of the United States and the public, as Murray did. Each day we add new material to the Librarys website (www.loc.gov) in an effort to make our resources available to people around the world. All of the 1900 Paris Exposition photographs that Murray brought to the Library can be accessed online along with thousands of images, manuscripts, and other items related to the experience of African Americans. There is no more fitting tribute to Murray-and to W. E. B. Du Bois and Thomas Calloway, and to all who contributed to the American Negro Exhibit-than that their work should be remembered, honored, and celebrated.

J AMES H. BILLINGTON

Librarian of Congress

O N D ECEMBER 28, 1899, W. E. B. Du Bois began work on a display for the Exposition des Ngres dAmrique-the Exhibit of American Negroes-at the Paris Exposition. As a rising star in the new field of sociology. Du Bois focused on a set of charts, maps, and graphs recording the growth of population, economic power, and literacy among African Americans in Georgia. But he also included photographs of what he called typical Negro faces, homes, businesses, churches, and communities that defied the image of blacks as impoverished, lazy, and ignorant-stereotypes held by many white Americans. Above all, the photographs Du Bois chose exemplified dignity, accomplishment, and progress. He presented his compelling vision of people of color at a grand and sweeping worlds fair that attracted more than 50 million visitors from its opening day on April 14, 1900, to its close some six months later in November.

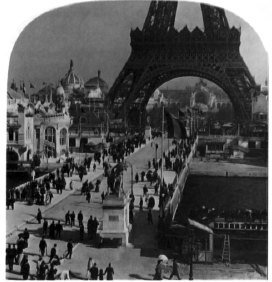

France had held international expositions since 1855, but the 1900 Paris Exposition was the most ambitious. It heralded the arrival of a new century, as it also celebrated the nineteenth centurys belief in progress, scientific accomplishments, and commercial and economic success. Country after country lined up to showcase its cultural and industrial achievements on some three hundred fifty acres bordered by Parisian landmarks: the Champs-Elyses, Htel des Invalides, Champ de Mars, and the Trocadro. On the magnificent Rue des Nations along the River Seine, the United States pavilion sat between those of Turkey and Austria-a last-minute concession by the French to move the Americans into the first rank of nations. The United States erected separate pavilions for displays of agriculture, forestry, printing, and publishing, as well as one featuring the products of the McCormick Harvester Company and another, the manufacture of American bicycles.

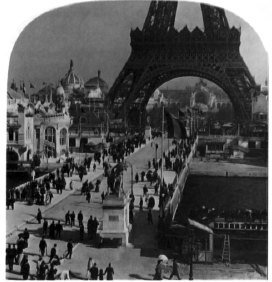

2. Monumental Portal, entrance to Paris Exposition, 1900.

These attractions competed with a host of technological and architectural wonders: a state-of-the-art moving sidewalk, the worlds largest telescope and globe, a giant champagne bottle that contained a small theater, and an elevator ride up the Eiffel Tower--which had been erected for the 1889 Exposition and was now newly painted a golden shade of yellow. Nor were Europes colonial interests unrepresented. There were displays from South Africa, Indonesia, and the Portuguese empire, and large pavilions for the French conquests of Indochina, Senegal, Cambodia, Tunisia, and Algeria. Although western Europe and the United States spoke of universal advancement and unity, they perceived Asia and Africa as primitive and exotic-and second-class. In fact, when the United States first planned its exhibits, financed by Congress with appropriations of $1.25 million, African Americans were accorded no place at all.

3. The Eiffel Tower with the Champs de Mars in the distance, Paris Exposition, 1900.

It was Thomas Calloway, an African American lawyer and educator, who called for black participation. Calloway had served as a state commissioner for the 1895 Atlanta Exposition, which brought widespread attention to black Americans. He understood that the new worlds fair in Paris was an opportunity to demonstrate African American progress and accomplishments to an even larger audience. He sent a letter to over one hundred representative Negroes in various sections of the United States, including Booker T. Washington, the head of Tuskegee Institute, and activist and clubwoman Mary Church Terrell. To the Paris Exposition thousands upon thousands will go, he argued, and a well selected and prepared exhibit, representing the Negros development in his churches, his schools, his homes, his farms, his stores, his professions and pursuits in general will attract attention as did the exhibits at the Atlanta and Nashville Expositions, and do a great and lasting good in convincing thinking people of the possibilities of the Negro."