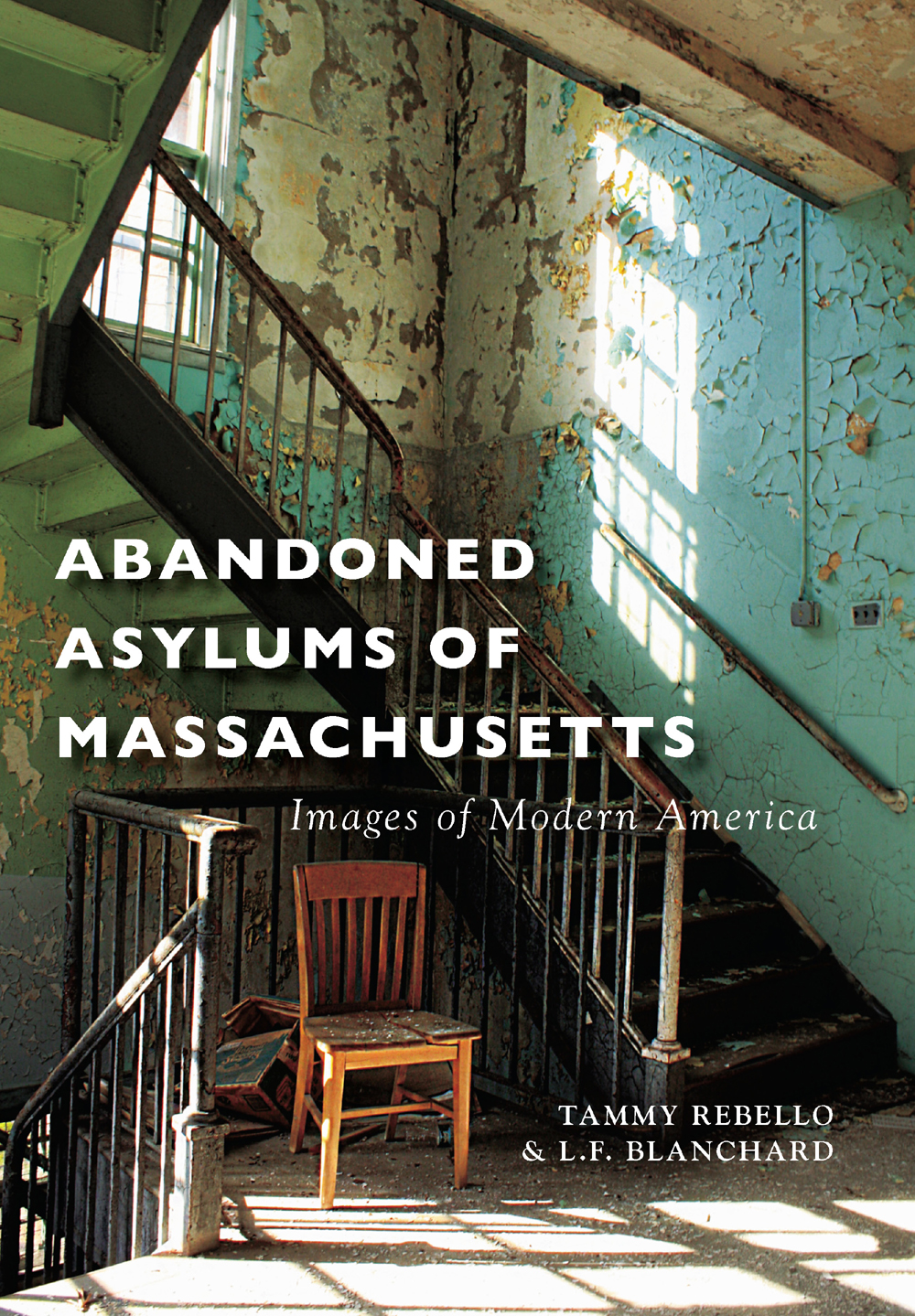

ABANDONED

ASYLUMS OF

MASSACHUSETTS

Images of Modern America

FRONT COVER: A chair sits in the stairwell of the partially abandoned Wrentham State School, now known as the Wrentham Developmental Center. (Courtesy of Tammy Rebello and TMR Visual Arts.)

UPPER BACK COVER: Furniture is piled high for trespasser access into one of the many cottages at Belchertown State School. (Courtesy of Tammy Rebello and TMR Visual Arts.)

LOWER BACK COVER: On the left, this is the only original building remaining on the campus of the Metropolitan State Hospital site in Waltham, Massachusetts. The administration building was named after Dr. William F. McLaughlin, a flight surgeon in World War II who was once an administrator here. In the center, Belchertown State School, which is in the beginning stages of demolition, houses a piano in a recreational building. At right, once a doctors residence, this house sits partially furnished on the campus of Paul A. Dever State School in Taunton. (All courtesy of Tammy Rebello and TMR Visual Arts.)

ABANDONED

ASYLUMS OF

MASSACHUSETTS

Images of Modern America

Tammy Rebello and L.F. Blanchard

Copyright 2016 by Tammy Rebello and L.F. Blanchard

ISBN 978-1-4671-1554-4

Ebook ISBN 9781439655603

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015956693

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Dedicated to all those who strive for a better tomorrow.

Tammy dedicates this book to: Amanda, Emalee, Austin, and Errickthe loves of my life. My brothers Tim and Josh for being my exploration buddies. Beth for being my partner in crime. My parents, for their unconditional love and support. Lastly, to Gram, you are my daily inspiration to work hard and achieve my dreams.

L.F. dedicates this book to: Cathy, for giving me reason to breathe. Mom and Dad, who gave me everything. Tina, for being a light in the darkness.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Christine (Tina) Runyan, PhD, ABPP; Brandi Silver, BS, MS, PhD; Kat OConnor; Andrea Martin, PhD; Jack Yates; Eli Minkoff, PhD; Doe West, MS, MDiv, PhD; Earl Storey; Don Gale; Cheryl Welcher, Westborough Historical Society; and of course, Erin Vosgien, Jeff Ruetsche, and the Arcadia staff for all of their support. Without them, this project would not have come to fruition.

Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of Tammy Rebello and TMR Visual Arts.

FOREWORD

We may want to believe mental illness is no longer stigmatized and that parity in health care exists, but the reality is one of continued marginalization of resources, limited access to high-quality health care, and a society that feeds shame as a main course to those suffering. There continues to be entirely too much sorrow and grief that accompany living with mental illness, or loving someone with mental illness, due to stigma, fear, uncertainty about getting help, and inadequate resources when help is sought.

Still, I have witnessed tremendous progress, particularly in the field of integrated health carein which mental health clinicians practice alongside primary care providers, and mental illness can be diagnosed and treated in primary care settings. The vast majority of visits to primary care providers are linked to one or more unmet behavioral health needs, such as stress, depression, anxiety, poor sleep, obesity, relationship issues, uncontrolled diabetes, or unremitting chronic pain. Having the right type of doctor, at the right place and at the right time, expands access to care, reduces augmentation, improves quality, reduces cost, andmost importantlydecreases suffering.

As a clinical psychologist working in primary care, arguably one of the front lines of health care, I am privileged to care for people alongside their family physician in a collaborative and continuous model of practice, which honors the emotional and physical ups and downs throughout a lifetime. But this model of care is not yet mainstream, and the pace of change towards integrated health care, rather than fragmented, feels glacial. There continues to be too many barriers to effective and compassionate mental health treatment, and the way in which health care is financed and appropriated in the United States is chief among them.

Health is not the absence of disease, it is a state of vitality and functioning in which mental and physical well-being are inexorably connected. But when health insurance companies deny member benefits for mental health assessment and treatment, there is no subtlety in the message that mental health is a luxury rather than a necessity for health. When each of us boldly acknowledges that the face of mental illness is not a strangers face, but rather is our neighbors face, our co-workers face, our sibling or childrens faces, or even your face or my face, the more we reduce stigma and shame. The more we disabuse misperceptions of mental illness as a moral failing or an excuse for violence, and actually fund social programs, health care, and meaningful treatment, the images on these pages will not only evoke disbelief and horror but also appreciation for how compassionate and accessible care can heal people and systems.

Tina Runyan, PhD, ABPP

Clinical Health Psychologist

Clinical Associate Professor

University of Massachusetts Medical School

Department of Family Medicine and Community Health

INTRODUCTION

The subject of mental health has been laced with negative connotations since the beginning of recorded time. As with many things, an unfamiliarity and misunderstanding of the origins of mental illness have played a heavy role in the persecution of those afflicted. From the Middle Ages to the Age of Enlightenment, Western societies attributed most mental illnesses to demonic possession. Even into the 20th century, the American public held misconceptions of the mentally ill, reacting to them with fear and horror.

Laws for the creation of first state asylum in the United States were passed in 1842 in New York. Utica State Hospital opened eight years later, due largely to the work of Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802July 17, 1887). Though she was born in Hampden, Maine, Dorothea spent much of her childhood in Worcester, Massachusetts, until she moved in with her wealthy grandmother in Boston. Growing up with an emotionally absent mother and an abusive father, she developed a sensitivity to the hardships suffered by others.

While teaching inmates at a local jail, she became aware of the cruelties inflicted upon the insane. She became a social activist and dedicated her life to the fight for a dignified life for the insane throughout the United States and in Europe as far east as Constantinople.

The culmination of her work was the Bill for the Benefit of the Indigent Insane: legislation that set aside 12,225,000 acres of federal land to be used for the care of the insane, blind, deaf, and dumb. Though the bill passed both houses of the United States Congress, it was later vetoed by Pres. Franklin Pierce in 1854. He argued that social welfare was the responsibility of the states. Stung by the defeat of her bill, Dix traveled to England and Europe. In 1854 and 1855, she conducted investigations of Scotlands madhouses, resulting in the formation of the Scottish Lunacy Commission to oversee reforms.

Next page