Contents

Guide

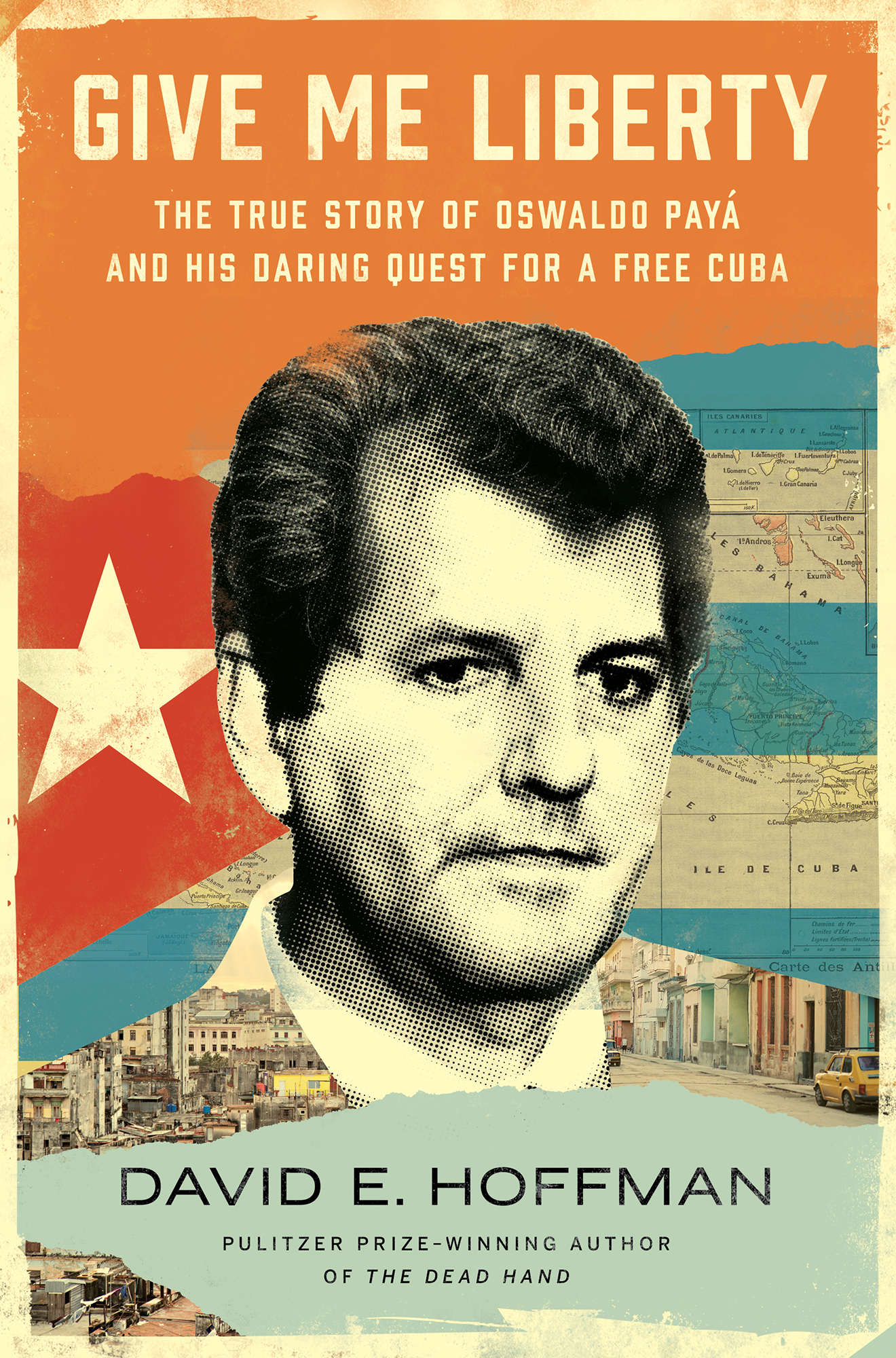

Give Me Liberty

The True Story of Oswaldo Pay and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba

David E. Hoffman

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author of the Dead Hand

To Carole

We cant be just the spectators of our own history. We must be the protagonists.

Oswaldo Pay,

Pueblo de Dios, No. 7

1987

Prologue HAVANA, JULY 22, 2012

B leary-eyed, Oswaldo Pay had been up all night, waiting for his daughter to come home. Rosa Mara was twenty-three years old, a university graduate in physics, lively and strikingly attractive, with a rebellious streak very much like her father. That she had been out all night, Oswaldo could do nothing, but he waited for her, worried about her safety, agitated, unable to sleep. She had promised to join him before dawn for the long and dangerous journey, staying one step ahead of state security.

Where was she?

Oswaldo was sixty years old, with thick, wavy hair the color of charcoal and a swirl at the peak of his forehead. He had deep rings under his eyes and worry creases sometimes rippled across his brow, but his brown eyes were soft, understanding, and patient. Oswaldo dressed casually, in jeans and a short-sleeved checkered shirt, the collar open wide, his shirt buttons absentmindedly askew. His voice had a slight nasal tone. He was a practiced orator, clear and articulate. He had a lot to say, and did.

By day, Oswaldo was an engineer who specialized in medical electronics, troubleshooting life-saving equipment at Havana hospitals. He worked with oxygen tanks, ventilators, and incubators. He took great satisfaction when he could help save a life.

But his great passion was to change Cuba, to unleash a society of free people with unfettered rights to speak and act as they wished. He called it liberation. He had devoted many years to the cause, shared with his wife, Ofelia Acevedo. At this moment she was away, visiting her parents, but she knew he was taking another step into the unknown. She sensed he was rushing toward something. She wondered why he was taking the chances, hurtling into the darkness once again.

Ofelia and Oswaldo had made a promise to themselves as newlyweds years before: their children would live in a free country. They would fight for it and never flee Cuba. Oswaldo had spoken out against Fidel Castros despotism since his own days in high school. He wrote dozens of manifestos and declarations, published underground handbills, formed a prodemocracy movement, and championed the Varela Project, a citizen initiative demanding free speech, a free press, freedom of association, freedom of belief, private enterprise, free elections, and freedom for political prisoners. He had never run from his values.

But lately, fear was choking him. The secret police, Seguridad del Estado, or state security, threatened his family. In fleeting encounters on the street, strangers came up to him and said simply, Be careful, or your children could be hurt. Oswaldo knew that state security could cause an accident, a bicycle run off the road, or a careless driver running a red light. They could plant drugs in a boys backpack, then haul him off to prison. They could detain and sexually assault a young girl. They could do anything. The thoughts were unbearable.

Oswaldo, shaken, had taken his three children, Oswaldito, Rosa Mara, and Reinaldo, to a convent of the Sisters of Mary Magdalene near their home in Havana. With assistance from the nuns, he showed them a hidden entrance leading to a concealed room. This was their refuge, he said; if he were ever arrested or if they were in serious trouble, they should come here, and the nuns would harbor them. The children thought it was a lark, but Oswaldo was serious. Another time, he turned to a visitor from Sweden and asked point-blank: What would it take to get asylum for my family?

Finally, in desperation, Oswaldo and Ofelia made a tough decision. The time had come to send their children out of Cuba. The two oldest, Oswaldito and Rosa Mara, applied for and were admitted to the University of Amsterdam. They were to go in August. The youngest, Reinaldo, might go to Spain. It was agonizing for Oswaldo and Ofelia to think about being apart from their children, to abandon the vow they had made to build a free country for them, but they felt they no longer had a choice. They sensed the dangers were growing.

Where was Rosa Mara?

Oswaldo was heading to Santiago de Cuba, 540 miles to the east, to train young activists and organize local committees for the Movimiento Cristiano Liberacin, the democracy movement he founded nearly twenty-four years earlier. He started it with friends in the parish of El Salvador del Mundo in Havana, where four generations of his family had anchored their Catholic faith. The movimiento had grown to more than a thousand members across the island, a civic and political movement, nondenominational but driven by the values of Christian democracy that had confronted fascism and communism in the twentieth century.

At this point, Fidel, almost eighty-six years old, had relinquished power to his brother Ral, who eased up slightly on the economy but maintained a hard line against any dissent, continuing the Castro dictatorship of more than five decades. Members of the movimiento were frequently jailed, harassed, interrogated, and pressured to become informers. State security kept Oswaldo under surveillance, and his name was blacklisted. He could not travel by plane, train, or bus without being immediately spotted. The trip to Santiago de Cuba would set off alarms if he took public transportation. Yet, from years of experience, Oswaldo had developed a clandestine method to evade surveillance. He could move relatively unseen in a rental car driven by tourists. State security might spend a few fruitless days looking for him. In this case, the tourists were two young men, from Spain and Sweden, both eager democracy activists who had arrived in Havana two days before.

The only problem was that they arrived unexpectedly early, and now he had to rush the trip, which had been planned for later. On July 26, in four days time, a holiday marked the anniversary of Fidels 1953 attack on the Moncada army barracks in Santiago de Cuba, the first armed assault of his guerrilla war. State security was on alert. To reach Santiago, a days drive, and get back, Oswaldo would have to hurry. He decided to leave before dawn, while darkness cloaked the streets.

Just before 6:00 a.m., Rosa Mara cracked open the front door.

Oswaldo was waiting in their tidy living room, with pale yellow walls and black-and-white checkered floor tiles. Rosa Mara steeled herself for his reproach. But as soon as he saw her, his anger melted away. She was safe. There was no time for questions. He had to leave before the sun rose. She had planned to go with him but was exhausted. She didnt dare ask him to wait for her. She knew he couldnt.

Oswaldo crossed the room and kissed her good-bye.

He grabbed his backpack. He motioned to Harold Cepero to grab his own overnight bag. Cepero was Oswaldos protg. While waiting for Rosa Mara, Oswaldo had spent the night talking with Harold about God, Cuba, democracy, and dictatorship. Oswaldo ranged over these topics naturally and passionately. With boyish good looks, tousled hair, faded jeans, and a white T-shirt, Cepero, thirty-two years old, was Oswaldos hope for a new generation of activists. He was helping Oswaldo train young people to fight for their rights, and he and Rosa Mara were preparing a youth magazine. The first edition was almost ready. As Harold stepped toward the door, Rosa Mara rushed up to him and put her hand on his shoulder.