This electronic edition published in 2016 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

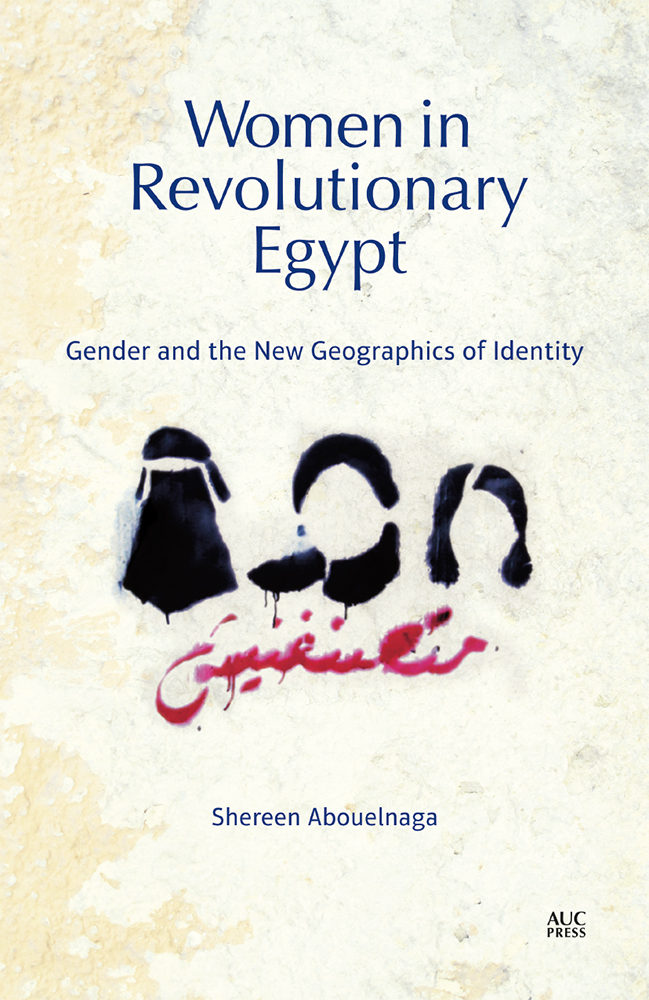

Copyright 2016 by Shereen Abouelnaga

Protected under the Berne Convention

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 747 8

eISBN 978 161 797 729 9

Version 1

If I didnt define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other peoples fantasies and eaten alive.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider

T he increase in the tendency to read the position of Egyptian women in isolation from as big an event as the Revolution was reason enough to make me write this book. On one side, the Western mediain all its formsworked on highlighting the violations of womens rights and bodies; on the other side, it totally ignored the wider sociopolitical context that is replete with protesting voices and sharp consciousness. This vision led to the portrayal of Egyptian women as victims and implied a nave attitude toward women. Similar to the Revolution, which has been challenged by its countermovement, the narrative of women was sidelined by its own counter that appeals more to minds that still believe the white mans burden exists. The way women have been exercising and performing their agency is unprecedented. This has not gone unnoticed by scholars of the region, and Egyptian academia is to be credited for having realized that at a very early stage. As the new geographics of identity has prevailed to enrich gender with other elements, the academic scene has kept up with developments. This book, however, does not assign itself the role of reading what happened since the eruption of mass protests in 2011; understanding the past opens potential possibilities of new forms of agency in the future. It is important, then, to fathom the meaning of agency this book employs.

I am indebted to the feminist minds that have challenged the social and political norms, and I have questioned the canonical theoretical principles. I am also indebted to all the feminist activists and scholars I have known and who never hesitated to transfer their experience. However, my main inspiration has been Susan Stanford Friedmans book, Mappings. Friedmans project of going beyond gender has informed my book and allowed several exits from theoretical impasses. It has also helped me understand situations that seemed totally incomprehensible, because they did not correspond to the expected or what should be. The high fluidity of the political scene has called for a constant change of subject positioning, a fact that had been totally foggy and nebulous for me and others as well. Any change of positioning seemed to call for vilification and condemnation. Amid the disappointments of the revolutionary trajectory, Friedmans theory worked like a deus ex machina. Identity is ipso facto flexible, fluid, and changeable, but amalgamating feminism, multiculturalism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, literary studies, and cultural studies for the purpose of reading the new geographics was the real inspiration. My thanks are also due to the American University in Cairo Press, especially Neil Hewison, whose trust enabled me to start the project, and Nadia Naqib, whose patience and support helped me finish. I must also express my deep gratitude to my editor and first reader, Caitlin Hawkins.

INTRODUCTION:

WHOSE SPRING?

And when we speak we are afraid

Our words will not be heard

Nor welcomed

But when we are silent

We are still afraid

So it is better to speak

Remembering

We were never meant to survive

From A Litany for Survival by Audre Lorde

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

From The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by S.T. Coleridge

Gender, gender everywhere, and not a space to win. Starting from March 2011, I kept almost humming this line in parody of Coleridges famous line in his Romantic nineteenth-century poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Unconsciously, I started humming it after the shameful virginity tests perpetrated by the military, but wasnt that too early? Perhaps, and perhaps not. I view this incident as a warning sign that worse incidents were bound to follow. The arguments and logicalities that ensued were disappointing and shocking, and they meant that the gender battle had erupted. The analysis of that incident was confined to whether it happened or not, emphasizing how authority (the military at that time) tends to oppress women. In the case of Samira Ibrahim, a victim of the virginity tests, nobody ever raised the issue of her origin (Upper Egypt), her age, her class, and her veil. These were essential factors that should have been taken into consideration to understand how genderas a main componentwill seek real agency. They were factors that, in the past, should have worked against the victim; paradoxically and fortunately, they worked for her. Without the Revolution, nobody could have sued the authorities. One wonders how between January and March 2011 society was capable of breaking the fear barriers.

The transformation of the sociopolitical scene was a corollary of the Revolution. It was neither positive nor negative transformation; just transformationa substantial change and a conspicuous shift toward the readiness to confront. The scene was overpopulated with voices and actors whose main concern was to designate and fix what came to be called Egyptian identity. The appearance of the identity discourse signified a crisis that was political, intellectual, ideological, and societal. In addition to going back to the obsolete definition of identity as fixed, stable, and unchangeable, gender was taken to be a marker of identity. This explains why the former Mubarak regime was so concerned with controlling and legitimizing a certain system of genderone that consolidates the power of the patriarch, in his multifarious manifestations, especially the father figure. Consequently, womens agency was hindered, and women were forced politically and discursively to conform to a monolithic modern image that has shielded all the sociopolitical and cultural differences and problems.

How the 25 January Revolution endowed women with the opportunity to initiate the route to agency while struggling over identity construction is the main concern of this book. I want to examine the emergence of womens agency in the post25 January moment, and, in order to do that, we have to trace many ideas back in time. The history of certain ideas could, in turn, trigger the history of gender. For example, the history and trajectory of nationalism in Egypt since the beginning of the twentieth century is, in my view, the history of the womens movement. Authoritarian regimes always find an excuse by which to control the peoples choices, to limit their practice of agency, to shrink their space of appearance, and to channel their anger through false causes. Women, on the other side, usually pay double the price as subjects and as women. The power of the central state and its system has always been so tight that the Revolution never managed to demolish them. Yet, every power carries within it the regimen of resistance. If the Revolution demolished anything, it was the principle of homogeneity; it turned out to be a mere illusory notion, propagated for a long time by the state. The Revolution has allowed for the eruption of differences previously silenced and suppressed through the incessant celebration of homogeneity through the state-run media. The Revolution marked the appearance of a real diversity on several levels: ideological, cultural, religious, educational, class-based, and gender-oriented. The revolutionary act has functioned as a political and cultural shock that effected subversions in a previously solid national gendered discourse. Nonetheless, the refrain remains, gender, gender everywhere, and not a space to win.