CONTENTS

Author's dedication:

In fond remembrance of Air Commodore Jeremy J. Jerry Witts RAF DSO FRAeS ADC 19502020, an outstanding strike pilot, inspirational leader, and treasured friend who flew and commanded Vulcan, Buccaneer, and Tornado squadrons and detachments, excelling in all he did. His skill, dedication, and extraordinary good humor were exceeded only by his steadfastness and great personal courage.

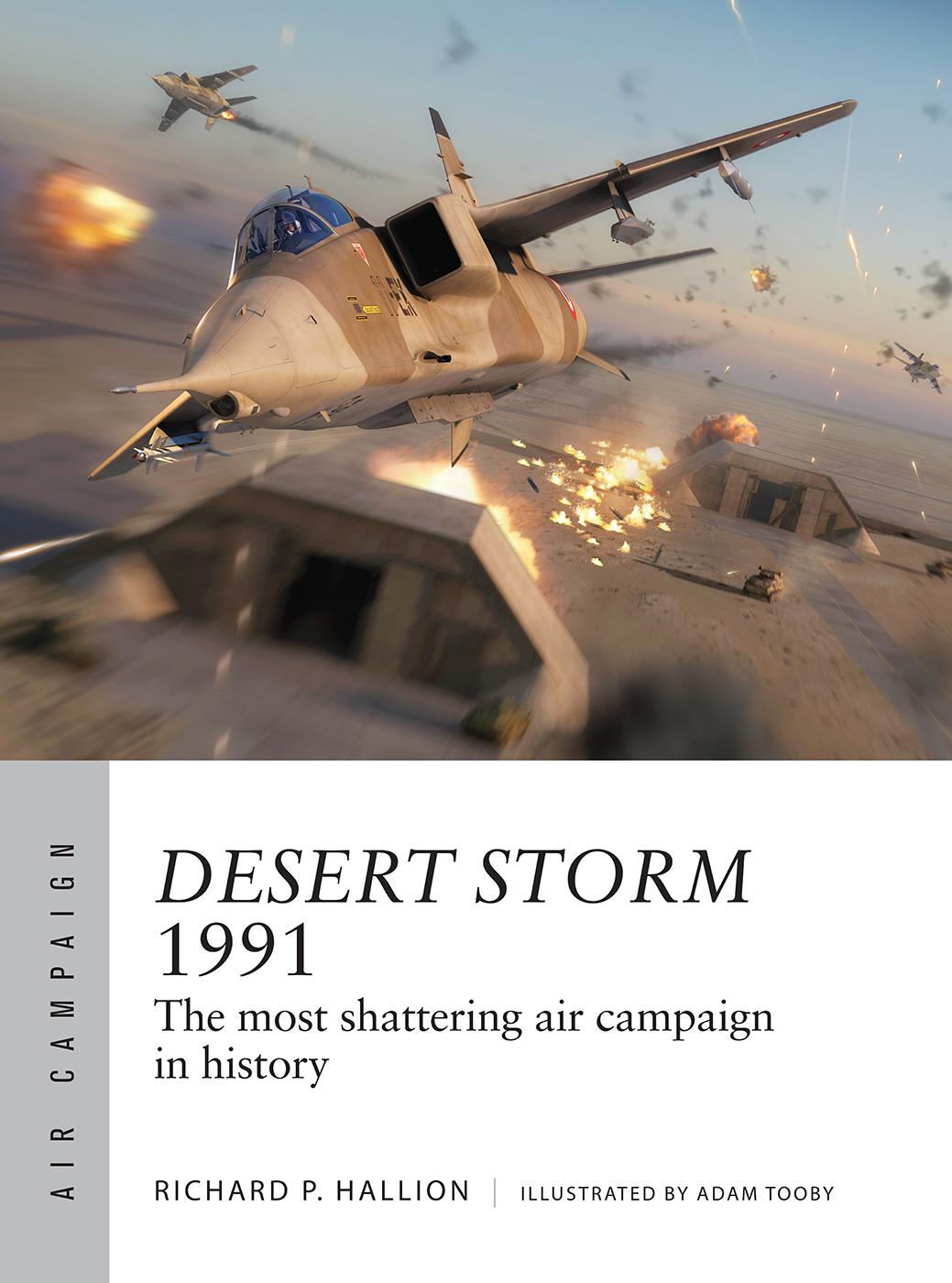

INTRODUCTION

In the last years of the Cold War, while the Soviet Union tottered towards collapse, the first major conflict of the post-Cold War era was brewing in the Persian Gulf. After the bloodbath of the IranIraq War ended in a ceasefire, an illusory peace lasted not quite two years. By wars end Iraq had greatly expanded its military forces, drawing its arms from both the West and East, but most notably France, the Soviet Union, and China. Bankrolled largely by the Gulf states, it now possessed the worlds fourth largest army and the sixth largest air force, with robust armoured, artillery, and missile forces. With Iran temporarily neutralized, Saddam Hussein unwilling to pay his war debts to the Gulf Cooperation Council and coveting oil-rich Kuwait, invaded that tiny country on August 2, 1990.

December 22, 1989: Standing on the infamous Berlin Wall, East and West Berliners celebrate the collapse of the East German state and the reunification of the two Germanys. (Department of Defense (DoD))

In response, the United States, Britain, and Saudi Arabia shaped and built a global coalition, pouring in troops and materiel in preparation for a high-technology and high-tempo war that, for scope and scale, eerily recollected NATOs 1980 plans for confronting the Warsaw Pacts massive armoured, air, and missile forces in Europe.

While strenuous diplomatic negotiations and successive United Nations (UN) resolutions failed to get Saddam Hussein to withdraw his troops from Kuwait, armchair critics predicted disaster should the Coalition attack dug-in Iraqi forces in Kuwait. Such an offensive, even if successful, would be long and costly, wrote commentators in The Baltimore Sun, entailing thousands and perhaps tens of thousands of American casualties. Even a retired US Army Chief of Staff, Gen Edward C. Shy Meyer, predicted up to 30,000 killed, wounded, and missing. Those extolling the merits of air power came in for special criticism, with economist and public intellectual John Kenneth Galbraith archly proclaiming theres no issue to be regarded with such doubt as this.

With diplomatic efforts exhausted, the Coalition went to war on January 17, 1991, quickly shattering Iraqs military and forcing its withdrawal from Kuwait after 43 days. The key to victory was evident from the first minutes of conflict: the Coalitions overwhelming air power employed by its air forces, navies, and armies.

Over the course of the war, fixed- and rotary-wing air power (informed and enhanced by reconnaissance aircraft, electronic intelligence collectors, and orbiting space systems furnishing intelligence, warning, weather, communications, and navigation) devastated Iraqs integrated air defense system (IADS); shattered its Air Force as an effective fighting arm; disrupted and persistently hindered effective command and control; prosecuted round-the-clock air attacks that pinned Iraqi troops in place; cut key rail and road links, thus denying them meaningful resupply; reduced fielded armour and artillery strength by direct air attack; frustrated (though it did not end) employment of theater-ranging ballistic missiles and battlefield rocket artillery; and demoralized soldiers so greatly that many contemplated killing their officers, others deserted (risking summary execution if found by Saddams enforcement squads), and some even took their own lives rather than endure what had become for them an unbearable ordeal of round-the-clock air attacks.

When Coalition ground forces breached Iraqi defenses to cross into Iraq and Kuwait, Coalition air power greatly facilitated their assault. In four days, the Coalition liberated Kuwait, seized 28,500 square miles of territory, and took over 87,000 Iraqi POWs. Combat concluded with a ceasefire at 0800hrs on February 28, and a truce at Safwan on March 3, 1991 ended the war. By then Iraqs army had shrunk from the worlds fourth largest to Iraqs fourth largest. Victory came at the price of 341 Coalition dead, and 776 Coalition wounded.

The air campaign plan reflected the bitter lessons and experience of Vietnam and the Middle East wars, coupled with an appreciation of what new technologies afforded: routine precision attack so that air strategists could plan in terms of number of targets destroyed per sortie, not numbers of sorties to destroy a particular target; stealthy strikes via the very low observable (VLO) radar signature F-117; space-based intelligence, navigation, communication, warning, and weather; airborne battle management and air-space deconfliction; and global-ranging mobility (and combat operations) via a tanker bridge. By emphasizing simultaneous, parallel war rather than sequential, linear war (as in previous air campaigns), air planners working at the direction of Lt Gen Charles Chuck Horner, the coalitions air commander left Iraqs airmen and air defenders both overwhelmed and on the defensive, unable to protect their ground forces in Kuwait or even the air space and territory of Iraq itself. While there were wild cards appalling weather, missile strikes against Israel and Saudi Arabia, the battle of al-Khafji, an enervating intelligence brouhaha in mid-campaign, and the al-Firdos bunker bombing none derailed the campaign, nor kept it from achieving its purposes.

Desert Storms air campaign marked the first time in military history in which air power was used as the lead force the veritable centerpiece in the strategy and execution of a war. As such, it radically redirected thinking about air power and its employment, evident in postwar doctrinal changes in many global militaries. It validated having a theater commander with reporting co-equal (if interdependent) air, land, and maritime component commanders, each possessing tasking authority across their respective air, land, and sea Coalition forces. It heralded as well a new era: routine precise, discrete, simultaneous, parallel, and diffuse attack from above.

The campaign plan emphasized nodal, effects-based warfare using the power of precision attack to reduce key Iraqi capabilities, not simply striking at sequential target lists or randomly bombing population centers. By not opting for a body-count-driven model of war emphasizing the punishing attritional clash of massed land forces, planners created a campaign that produced (by previous standards) mercifully low casualties to both attacker and defender, a characteristic of other air-dominant wars since then.

It was, in short, war according to Sun Tzu, not Clausewitz. Military analysts, war college cognoscenti, and historians continue to debate whether (as some have said, including this author) that it constituted a Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA). But that it transformed perceptions, expectations, doctrine, strategy, and employment of air power is beyond doubt.

CHRONOLOGY

1988