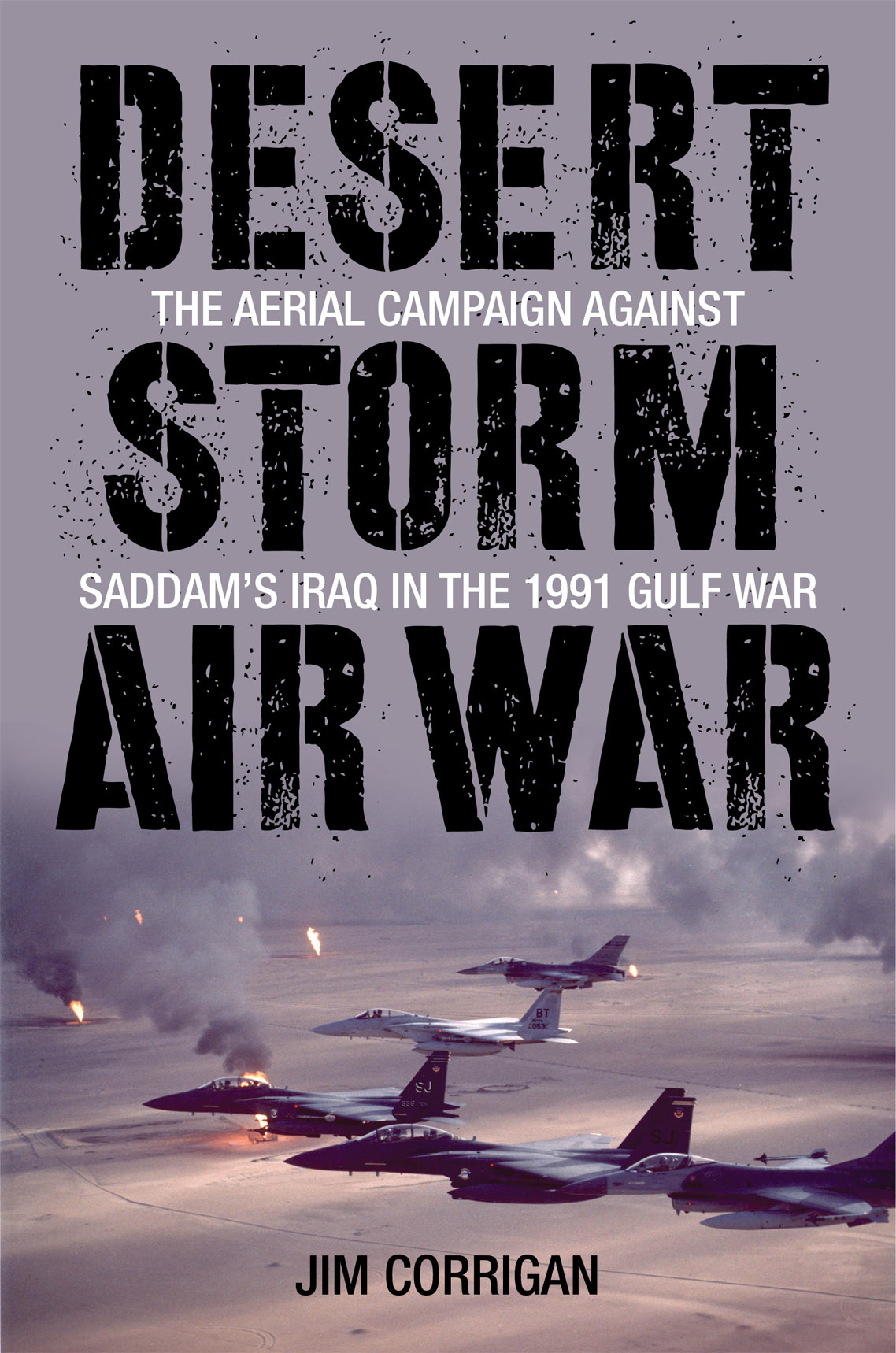

DESERT STORM AIR WAR

Published by Stackpole Books

An imprint of Globe Pequot

Trade Division of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2017 Jim Corrigan

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-0-8117-1776-2 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8117-6589-3 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

AUTHORS NOTE

This book uses NATO reporting names for Soviet and Chinese military equipment deployed by Iraq, such as the MiG-25 Foxbat .

Mach 1 is the speed of sound, or roughly 765 miles per hour depending on environmental conditions.

A kill box is a map square where warplanes may attack ground targets freely and without further authorization.

The golden BB is every combat pilots nightmarea lucky shot, perhaps even fired blindlythat brings down an aircraft.

Foreword

By Col. Ralph Getchell (Ret.)

Stealth pilot and squadron commander during Operation Desert Storm

TO MOST AMERICANS, MENTION OF THE 1991 GULF WAR CONJURES UP CNN broadcasts of grainy videos showing high-tech U.S. weaponry in action. Certainly, for the average taxpayer there was a certain satisfaction in seeing the results of the Reagan-era military buildup, which had been intended to counterbalance the Warsaw Pact. The armys M1A1 main battle tank and Bradley Fighting Vehicle, the navys Tomahawk-equipped fleet, and the air forces stealth aircraft and precision weapons all had their turn in the media spotlight, touting our technological superiority over potential adversaries equipped with Soviet-made hardware.

This modern arsenal was developed to provide our national leaders with the tools necessary to pursue and achieve national objectives. In the summer of 1990, the overarching objective regarding the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait was clearly and concisely stated by President George H. W. Bush in his famous this shall not stand speech. In the months of coalition-building that followed, the objectives became more specific: to expel the Iraqi invaders from Kuwait and substantially reduce Iraqs ability to attack neighboring countries in the future.

At first glance, this may have seemed an easy task for the worlds greatest military power. The U.S. military by itself certainly had the force structure, but first we had to move many units based in Europe and the Pacific Rim, which supported defense commitments there. U.S. military units on the East Coast were over 6,000 miles from Baghdad. The ability to get an adequate force to the fight would depend on an armada of military and civilian aircraft and ships that could move the kind of forces needed. The Iraqi army at the time was the worlds fourth largest, with Russian-made tanks and a huge and widely dispersed support infrastructure.

Much has been written about the new weapons brought on board during the Reagan buildup, but the U.S. success in Desert Storm had its roots in the lessons learned more than twenty years earlier by those who served during the Vietnam conflict. While the U.S. military enjoyed technological superiority then as well, it was applied in a fragmented fashion.

As a lieutenant fresh out of pilot training, I was surprised to learn that the Vietnam air war was actually several campaigns fought simultaneously in a relatively small area. At one point, there were as many as seven different U.S. military entities conducting their own air operations with little or no coordination. For example, Thailand-based fighters of the 7th Air Force conducted air strikes in North Vietnam while Navy 7th Fleet aircraft independently struck nearby targets in their own assigned area. Meanwhile, Guam-based B-52s attacked target sets determined by President Johnson and attack plans developed by Strategic Air Command staffers in Omaha. When forces were tasked to work together, deep-rooted differences in doctrine, terminology, and communications made it extremely difficult for them to operate efficiently and effectively.

Although the problem was obvious, our military was slow to change. As late as 1983, when the United States invaded Grenada to expel Russian-backed Cuban forces, the services still couldnt talk to one another. Congress gave us a push with the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986, which directed that the Commanders in Chief (CINCs) of the Unified Commands, historically designated for the European, Pacific, and South American theaters, would report to the president through the secretary of defense rather than through the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Commander of Central Command had responsibility for the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia. This arrangement mitigated much of the interservice rivalry evident during Vietnam by focusing on the needs of the theater warfighter rather than the self-serving biases of the Washington-based service headquarters.

Within each unified command, the CINCs were expected to designate a single joint-force air component commander to control all aircraft operating in the theater, regardless of which service provided the aircraft. Similarly, a single joint-force ground component commander would control all U.S. ground forces engaged in that theater. In 1988, General Norman Schwarzkopf, who had been a battalion commander in Vietnam and in the joint command group for Grenada, was appointed CINC of Central Command (CINCCENT). His air component commander, Lt. Gen. Chuck Horner, had two tours in Vietnam in the F-105 fighter-bomber.

While Schwarzkopf was singularly responsible for Central Command, Horner was dual hatted and also served as the commander of Tactical Air Commands 9th Air Force. Ninth Air Force encompassed all TAC aircraft in the Eastern United States and provided combat-ready forces to support wartime operations for European and Central Command. In this assignment, and earlier as the commander of fighter wings at Luke and Nellis Air Force bases, Chuck Horner had a reputation as a no-nonsense leader who always focused on improving practical combat capability. To Horner and other leaders in the fighter community, the keys to growing a force of capable fighter pilots were more training flights, and with greater realism.

As a relatively new pilot flying A-7D Corsair IIs with the Flying Tigers of the 23rd Tactical Fighter Wing, I directly benefited from Gen. Bill Creechs initiative to increase the so-called utilization or ute rate, which was the average number of flights flown by each TAC aircraft per month. In some units, this program nearly doubled the amount of training sorties a combat-ready pilot could fly each month. We spent less time training with twenty-five-pound practice bombs and had more opportunities to drop full-scale ordnance. This program not only improved the number of training flights each pilot received, it honed the capability of maintenance units to support the faster tempos of combat conditions. General Creech also instituted the Checkered Flag training program, which required all TAC aircrews to study warplans and operational procedures established by the unified commands for possible combat in their theaters.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.