STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

: Permision to reprint lyrics. Copyright 201215 Derrick Wang

Cover 2018 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

This book is an independent publication and is not associated with or authorized, licensed, sponsored, or endorsed by any person, entity, product, or service mentioned herein. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners, are used for editorial purposes only, and the publisher makes no claim of ownership and shall acquire no right, title, or interest in such trademarks by virtue of this publication.

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or .

Foreword

by Mimi Leder

I am not a lawyer. I am not a judicial scholar. I am a filmmaker whose lifes work has been to bring aspects of the human experience to the screen, hopefully inspiring a greater understanding of our shared humanity through the power of cinematic storytelling.

I came of age in the late 60s and early 70s, a time of great promise and turbulent social upheaval in the United States. It was the birth of the Peace Corps, the National Organization for Women, and landmark legislation including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965; the appointment of the first African American Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall; and the historic March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.s inspiring I Have a Dream speech.

Even as our social justice movements and human rights agendas took root and we embraced universal themes and dreams of equality, we resisted an unpopular war in Vietnam, faced the Cuban Missile Crisis, and endured the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Dr. King, and Robert F. Kennedy within a five-year period. We walked on the moon, but our cities and college campuses were torn apart and wrought with violence as the pain of the civil rights movement moved to the streets. Women were routinely discriminated against in wage and hiring practices and limited by established social mores reinforced by a diminished legal statusstrictly on the basis of sex.

When I was accepted to the Conservatory of the American Film Institute I was twenty years old, the first woman ever admitted to the cinematography program. Much of the material I studiedin fact the history of cinema as we knew itwas told through the lens and filter of male filmmakers. Womens stories and experiences had been written and photographed by men since the creation of the medium. That said, the Golden Age of Hollywood in the 1920s brought us films through a female lens from Mary Pickford, Frances Marion, and Dorothy Arzner, and it wasnt until the 30s and 40s that the industry turned into a business driven by men. As I entered this male-dominated field I quickly learned how many doors could be shut in my face strictly because I was a woman and how vital it was for me to follow my path. Thankfully, my father, a feminist, always told me that I could do anything, and so I did.

It was thirty-two years after my career began that I was given the opportunity to direct a movie about Ruth Bader Ginsburg, one of the most remarkable experiences of my life. Meeting Justice Ginsburg and researching the impact of her work and the obstacles she overcame gave me a new and powerful appreciation for how the opportunities and rights I enjoy stem from her work. While she had contemporaries who fought before and alongside her during the seminal judicial victories that profoundly moved the needle for womens equality, hers was a unique intellectual rigor and belief in the importance of the law not just as the foundation of our democracy, but as an instrument of change.

Her origin story, which inspired my film On the Basis of Sex, details the strategic path the young Ruth Bader Ginsburg charted, taking aim at specific discriminatory statutes and choosing her plaintiffs carefully, demonstrating that gender discrimination was harmful to women and men. It reveals not just the skills and legal expertise she possessed but the passion she applied to finding a path forward to change the prevalent notion that women needed to be dependent on men.

She continues, at this writing, to uphold her values on our highest court, a champion for the same principles that changed the moral compass of our nation in the last century: that all people are entitled to equal status and protection under the law. Perhaps her greatest legacy is not just the judicial victories that reshaped our culture. Perhaps it is the legacy of dissent and the permission, the mandatethe inalienable rightshe demonstrated for all people to have a seat not just at the table, but also on the bench.

Some of us mirror and document the times in which we live. Some of us are fortunate enough to change the times in which we live... and to manifest a more just future. Justice Ginsburgs chambers, which I had the honor to visit, are decorated with an artists rendering of the Hebrew phrase from Deuteronomy Tzedek, tzedek, tirdof (Justice, justice thou shalt pursue). On behalf of my daughters, and for all of our sons and daughters, I say to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Thank you.

July 2018

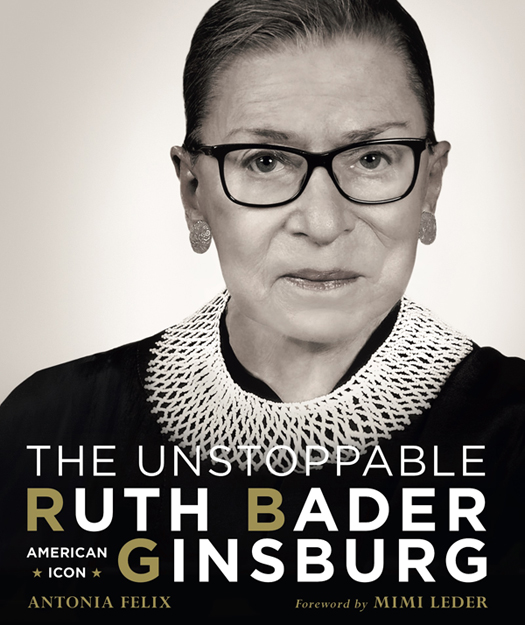

Justice Ginsburg speaks at the New York University Annual Survey of American Law dedication ceremony, April 14, 2010.

INTRODUCTION

The Whole T(Ruth)

When a handful of Ruth Bader Ginsburgs female students at Rutgers University School of Law were trying to launch a journal about womens rights in 1971, one potential funding source called back to say no. The staffer, speaking on behalf of the directors of a major foundation, said, They think the womens movement is a fad and will be gone in a year.

That kind of dismissal was nothing new to the women who had decided to go into the law or to Professor Ginsburg, who had started teaching at Rutgers Law in 1963 as the second woman in the facultys fifty-five-year history. Women were only 4 percent of the profession in the early 1970s; today they make up 36 percent of American lawyers. Much of the reason theyve gained that ground in the past fifty years is the womens movementand the legal genius of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

AMERICAN ICON

AMERICAN ICON