Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

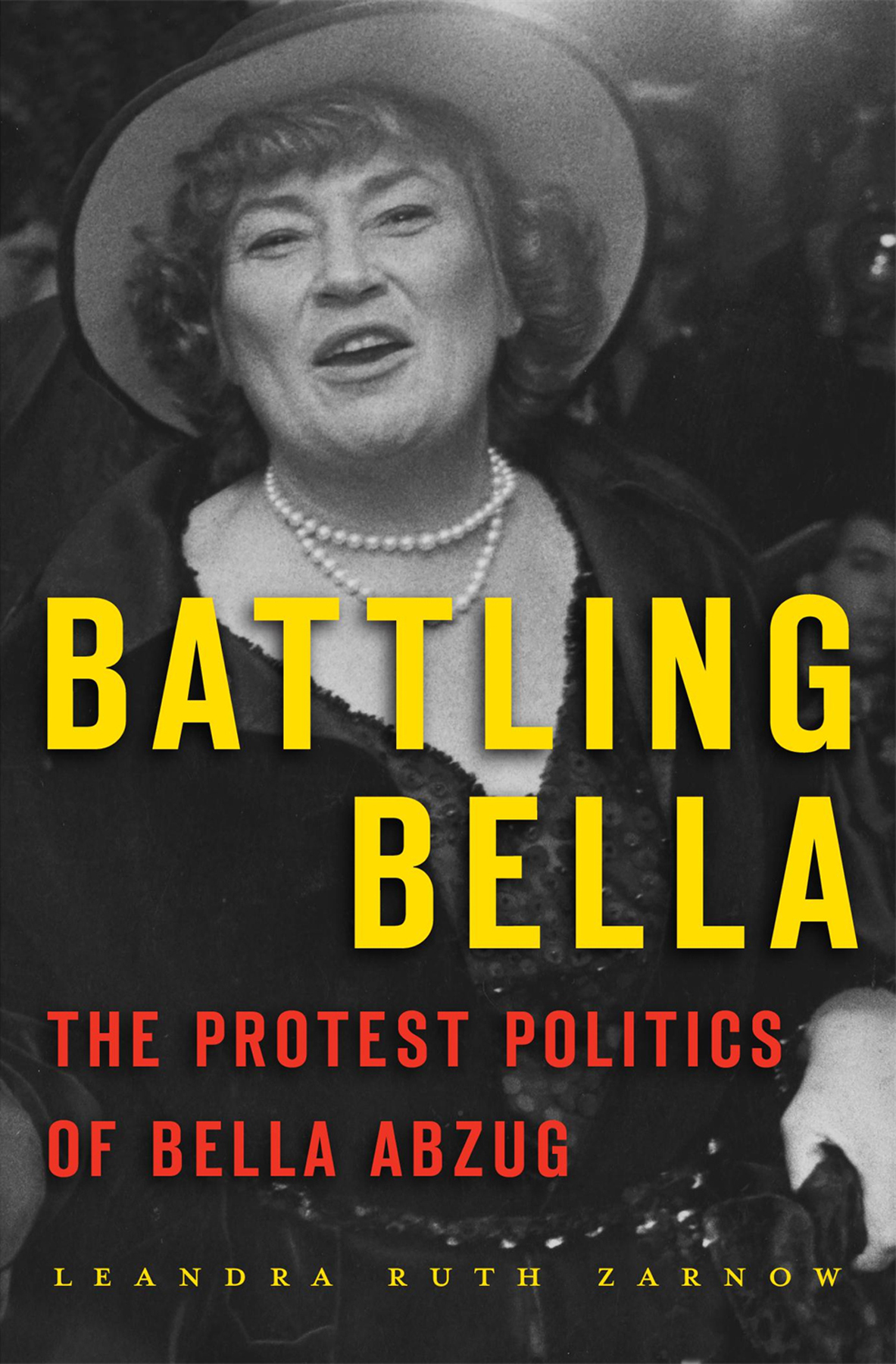

Battling Bella

THE PROTEST POLITICS OF BELLA ABZUG

Leandra Ruth Zarnow

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

2019

Copyright 2019 by Leandra Ruth Zarnow

All rights reserved

Publication of this book has been supported through the generous provisions of the Maurice and Lula Bradley Smith Memorial Fund.

Jacket photo: Ron Galella / Getty Images

Jacket design: Jill Breitbarth

978-0-674-73748-8 (alk. paper)

978-0-674-24376-7 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24377-4 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24375-0 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Zarnow, Leandra Ruth, 1979 author.

Title: Battling Bella : the protest politics of Bella Abzug / Leandra Ruth Zarnow.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019014313

Subjects: LCSH: Abzug, Bella S., 19201998. | WomenPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Democratic Party (U.S.) | United StatesPolitics and government20th century.

Classification: LCC E840.8.A2 Z37 2019 | DDC 320.082/0973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019014313

For my parents, boundless believers.

And Juan Cisneros, for whom New Yorks city lights dimmed too soon.

CONTENTS

This book began with two moments in the past. As a student at Smith College in the late 1990s, I worked at the Sophia Smith Collection, a womens history archive. There, I came across a swirly signature, Bella, when I was cataloging correspondence in a collection Gloria Steinem had recently donated. Curious, I learned Bella Abzug was the mystery scribe, and that First Lady Hillary Clinton was not the only woman in politics to be at once revered and reviled. This discovery brought me back to an earlier memory of a story my father had told. It was August 1970. He was twenty-four years old, an organizer for Students for a Democratic Society and the Vietnam Vets Against the War, and was visiting relatives in New York City. Proud members of the National Organization for Women, they led him into a stream of women marching in the Womens Strike for Equality, a historic mobilization held on the fiftieth anniversary of womens suffrage. The day was unforgettable. Most vivid in his memory was the impassioned oratory of a lady with a hat. This was Abzug, and this book is as much for the young people she inspired then as it is for a new generation untouched by her vibrancy.

My narrative came to form in the wax and wane of the George W. Bush and Barack Obama presidencies as they grappled from different angles with an elusive terrorist target, global economic strains, and the complexities of a more diverse nation. It reaches readers at a historic political impasse amid Donald Trumps presidency. Some Americans have gained comfort in the hope of recovering an imagined great America, while others have protested and resisted this new nationalist idiom.

Bringing protest to politics, Congresswoman Abzug may be a visionary for our times as much as hers. The will to resist became a central posture in 2017, a year of protest unlike any in the early twenty-first century. Fifty years prior, Abzug blazed onto the national scene as a potent force of protest and resistance. Working on the edges of the political mainstream, she stretched its epicenter closer to her. Her thinking was radical, though some of her most outrageous ideas and goals have since become the norm.

I place Abzug as a participant in the American Left, a broad political community to which she proudly belonged. As I completed interviews for this book, some individuals close to Abzug expressed discomfort with my choice to focus on her leftist past and to use the term Left alongside the more ambiguous radical. They are understandably fearful that being truthful about Abzugs history will provide fuel for the partisan fire that continues to swirl. Yet, to deny her self-labeling would be ahistorical. It would also limit understanding of the interactive relationship between leftists and liberals, and particularly how Abzug helped extend progressive pressure within the Democratic Party and Congress in the early 1970s.

Abzug was not one to save much before she held political office. I am beholden to others for valuing what she did not preserve on her own. One close friend, Amy Swerdlow, can be credited for keeping legal pads from the 1960s filled with ideas Abzug tried out in Women Strike for Peace and formalized in Congress. Sitting down with those who knew her, hearing moving and wild stories about this vivacious woman, has been a joy of this project. Oral interviews colored the inert remnants of life stored in archives and allowed me to imagine Abzug in action. I have also taken care to dwell on the occasions when she paused to jot down her reflections.

I am quite deliberate in my attempt to write women into the more conventional annals of political history, a genre that remains partial to great men. Early womens historians brought attention to the domestic and intimate aspects of life when all of history seemed to be about business and politics. I work in this tradition, while also exploring Abzugs high-velocity political life. What fueled her passion, how she crafted her politics, and why she saw such promise in the democracy she critiqued so deeply is what I have sought to capture here.

I come out of the peace movement and womens rights.

They thought I was a lunatic. Now these causes are being supported by a majority of the people. Ive been out front. Everybodys caught up.

BELLA ABZUG

NDY WARHOL HAILED A CAB down to his studio overlooking Union Square, where Bella Abzug waited for a portrait sitting commissioned by Rolling Stone magazine. Warhol took special delight in this assignment. He thought Abzug had panache. He appreciated her steadfast advocacy of gay rights at a time when few politicians would touch the issue, and he enjoyed running into her at parties. Warhol chronicled these exchanges in his diary along with Abzugs media appearances and her electoral losses and wins. What do you think New York needs most? a journalist asked Warhol in September 1977. A woman mayor. Bella Abzug. Shed be great, he replied. Abzug kicked off her candidacy earlier that June by cruising the streets of Manhattan in a gold convertible with the swagger of a victor on the make. A week after her announcement, Warhol was tasked with creating presumably the earliest portrait of New Yorks would-be woman mayor.

Warhol loved a certain kind of outrageous nerve, a quality Abzug did not lack. In the final silk screen, the rose did not appear. Instead, Warhol opted to focus on his subjects hat, depicted in jet black and accented by a backdrop of blue, purple, turquoise, and coral pastels. The resulting halo effect invoked religious iconography, a nod to Abzugs self-confidence and fame.

Actress Shirley MacLaine loved Warhols screen print of her friend so much that she displayed it on her bureau. Warhols portrait elevated Abzug, the most influential woman in US politics at the time, to the realm of an American cultural icon. It also served as a counterpoint to the usual portrayals of Abzug as an uncouth, bossy loudmouth. But the image did nothing for her election prospects. In a twist of fate, Abzugs