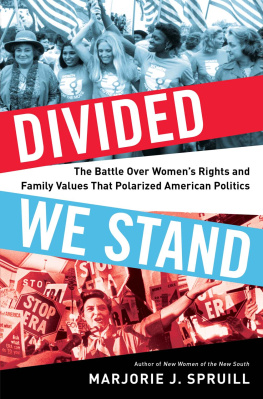

Divided We Stand

To my husband,

Don H. Doyle

Also by Marjorie J. Spruill

New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States, by Marjorie Spruill

One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement, edited by Marjorie Spruill

Votes for Women: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation, edited by Marjorie Spruill

The South in the History of the Nation: A Reader, Volumes 1 and 2, coedited by Marjorie Spruill and William Link

Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives, Volumes 1 and 2, coedited by Marjorie Spruill

South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times, Volumes 1, 2, and 3, coedited by Marjorie Spruill

Contents

For myself, Houston and all the events surrounding it have become a personal landmark in history; the sort of event one measures all other dates in life as being before or after It raised hopes for a new openness and inclusiveness in national political events to come.

GLORIA STEINEM, AN INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT, WHAT WOMEN WANT , 1978

The weekend of November 1821, 1977, in Houston was the decisive turning point in the war between Womens Lib and those who are Pro-Family. Houston was the Midway battle that determined which is the winning side.

PHYLLIS SCHLAFLY, PHYLLIS SCHLAFLY REPORT , DECEMBER 1977

There were two womens movements in the 1970s: a womens rights movement that enjoyed tremendous success, especially early in the decade, and a conservative womens movement that formed in opposition and grew stronger as the decade continued. Each played an essential role in the making of modern American political culture.

Tensions between feminists and their conservative critics exploded in 1977 during a series of state and national conferences culminating in a National Womens Conference held late in the year in Houston, Texas. Known as the International Womens Year (

The

The Houston conference and the preliminary state meetings leading up to it proved to be thoroughly polarizing events. As womens rights supporters put aside their differences and united behind an expansive set of feminist goals, conservative women who opposed any of those goals joined forces to challenge themwith enduring consequences for the nation.

Divided We Stand draws the connection between the events that divided American women in the 1970s and the subsequent polarization of American politics at large as the two major parties chose sides between feminists and their conservative challengers. Whereas in the early 1970s both Republicans and Democrats supported the modern womens movement, by 1980 the GOP had sided with the other womens movement, the one that positioned family values in opposition to womens rights.

All too often this transformation in national politics is explained with little attention to the role of women and womens issues. They are at the center of the story told here. Divided We Stand provides insights into contemporary politics as it examines the growing power of feminism in the governing establishment, the growth of the conservative opposition, and the competition between them for influence in American politicsa battle that reached a crucial turning point in November 1977 in Houston.

On November 18, 1977, tens of thousands of people poured into Houston for a weekend National Womens Conference, including the two thousand delegates elected at the preliminary meetings the past summer, members of the presidentially appointed IWY Commission that had organized the conference, one hundred observers from fifty-six countries, and thousands more eager to be a part of this historic event.

Over 1,500 reporters, photographers, and writers had requested press passes for what was turning out to be a

The National Womens Conference seemed to be the apogee of the modern womens rights movement, the crest of the second wave of American feminism. In many respects it resembled a national party convention. Delegates came from every state and territory, many arriving with hats to wear on the convention floor: cowboy hats from Wisconsin, tricornes labeled FREE D.C. from the District of Columbia, and jibaros (wide-brimmed sugarcane workers hats) from Puerto Rico. Apart from the fact that all but six of the delegates were women, however, the conference was far more diverse than any political gathering in American history in terms of race, ethnicity, class, age, occupation, and level of political experience.

Delegates ranged from students and homemakers attending their first womens conference to presidents of national womens

Not surprisingly, the conference attracted the nations most famous feminists. Betty Friedan, author of the 1963 bestselling book

Celebrities in every field, from academics to athletics, lent luster to the gathering, proud to be associated with this extraordinary event. World-famous anthropologist Margaret Mead, whose pioneering work on gender roles as social constructions varying from culture to culture laid the intellectual foundation for the academic field of womens studies and the modern womens movement itself, would give a plenary address. Tennis star and leading advocate for women in sports Billie Jean

Several of the celebrities were IWY Commission

Bella Abzugformerly a congresswoman from New York City and admired for her feisty, outspoken manner and amazing success in pushing feminist reforms through Congresswas the IWY Commissions presiding officer. Appointed by President Jimmy Carter, she was the star of the show, easy to spot in her trademark wide-brimmed hat. Sally Quinn, covering the weekend for the Washington Post, reported that in Houston women clustered around Abzug, eager for her attention: Everywhere she went the women would come at her, pull at her, tug at her arm, her jacket, her skirt. Bella this and Bella that. It reminded one of the mother taking her brood to the circus and everybody wanting peanuts and popcorn at the same time.

Abzug had been the primary advocate for the IWY conferences. A liberal and longtime supporter of the civil rights movement, Abzug was eager for underrepresented groups to enhance their political clout by joining forces. She saw the IWY as an opportunity to reach out to minorities and the poor, to develop grassroots support for the feminist movement, and to unite American women behind a feminist agenda that served them all.

Women active in national politics in both parties were eager to be a part of this federally funded extravaganza. They came to Houston in droves. Famous Republicans included Jill Ruckelshaus, who had served as presiding officer of the IWY Commission under President Gerald Ford; Congresswoman Margaret Heckler of Massachusetts, who represented the House of Representatives on the IWY Commission; Mary Louise Smith of Iowa, former chair of the Republican National Committee; and Mary Crisp, the current RNC cochair. Elly Peterson, Republican cochair of ERAmerica, a new bipartisan organization created by the IWY Commission to coordinate ratification efforts, was in Houston along with Democratic cochair Liz Carpenter. The two would preside over a glittering preconference fund-raiser for the ERA.

Democrats included Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman of New York, who served on the IWY Commission. Congresswomen Pat Schroeder of Colorado and Lindy Boggs of Louisiana were also in Houston. Former congresswoman Martha Griffiths of Michigan, revered by feminists for the role she had played in adding protection against sex discrimination to the 1964 Civil Rights Act and steering the ERA through Congress, was also a commissioner. Texass own Barbara Jordan, a congresswoman who electrified the 1976 Democratic National Convention, would lend oratorical brilliance to the conference as the keynote speaker.