Contents

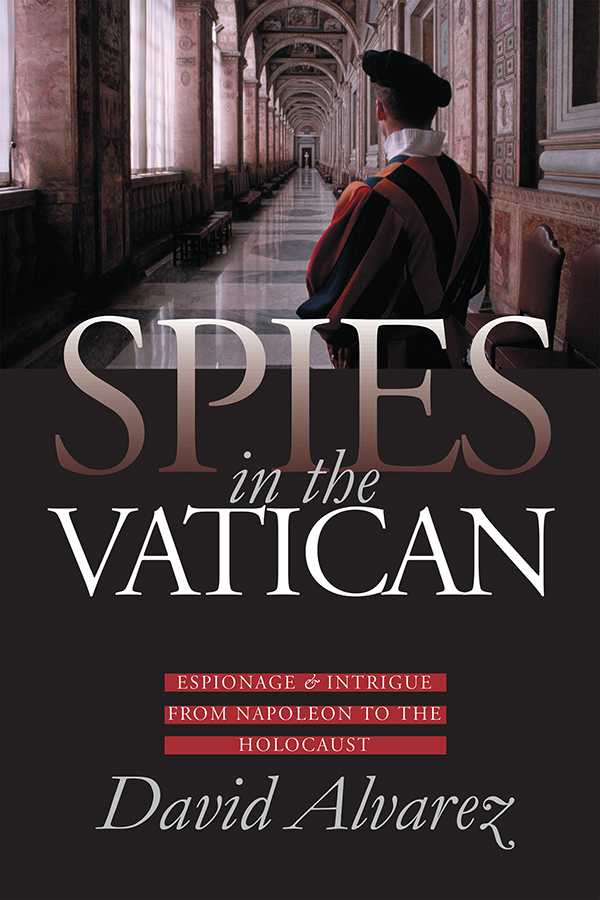

S PIES IN THE V ATICAN

MODERN WAR STUDIES

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor

Raymond A. Callahan

J. Garry Clifford

Jacob W. Kipp

Jay Luvaas

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

Dennis Showalter

David R. Stone

Series Editors

S pies

in the

V atican

Espionage & Intrigue

from Napoleon to the

Holocaust

D AVID A LVAREZ

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas

2002 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66049), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Alvarez, David J.

Spies in the Vatican : espionage and intrigue from Napoleon to the Holocaust / David Alvarez.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0700612149 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780700622894 (ebook)

1. EspionageVatican CityHistory19th century. 2. EspionageVatican CityHistory20th century. 3. Intelligence serviceVatican City19th century. 4. Intelligence serviceVatican City20th century. I. Title.

UB 271. V 38 A 48 2002

327.12456'34'009034dc21 2002008241

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z 39-48-1984.

For Donna

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book could not have been written without the advice and assistance of friends and colleagues. Several individuals helped me chase down intelligence records: John Taylor and Greg Bradsher at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland; Monsignors Charles Burns and Marcello Camisassa at the Vatican; Elisabeth Giansiracusa and Roberto Ventresca in Rome; and Vincent Leguy in Paris. John Ferris and Michael Phayer read the manuscript and helped me see where it needed improvement. Two veterans of the intelligence wars in Rome, William Gowen and Martin Quigley, patiently responded to my questions concerning American operations at the Vatican. Cardinal Silvio Oddi recalled life in the papal diplomatic service in World War II. Eva Kuttner shared her memories of Father Robert Leiber. Brian Sullivan repeatedly demonstrated that no one knows more about Mussolinis intelligence services than he. Larry Gray helped me better understand the figure of Felix Morlion. From Charles Gallagher I first learned of Monsignor Joseph Hurleys work for the American government. Mike Briggs, my editor at the University Press of Kansas, believed in this book when it was only an idea.

The Faculty Development Fund at Saint Marys College of California subsidized research trips to distant archives. No one will be happier to see this work in print than the funds directors.

My family remained cheerful and patient throughout the process even when I did not. This is as much their book as it is mine.

INTRODUCTION

Spies in the Vatican. The words evoke images of frescoed corridors and crimson-robed prelates, furtive meetings in shadowy crypts and whispered confidences in incense-scented chapels, cunning cardinals and devious monks, political intrigue and dark conspiracy. The words suggest the plot of a hundred thrillers and mysteries, the story line for a dozen screenplays. The words and images are doubly powerful because the popular imagination, convinced of the power of the Papacy, intrigued by the mystery and glamour surrounding the Vatican, and schooled in tales of ruthless and scandalous Renaissance popes, is all too ready to believe that the Vatican has long been a major capital of the secret world of espionage and that popes, no less than kings and prime ministers, presidents and dictators, inhabit a secret world of spies, assassins, saboteurs, and clandestine operations. The images are so powerful that even diplomats, politicians, military officers, and other professional observers of international affairs have often succumbed to the stories and legends of papal espionage.

Historians, whose job description (at least until recently) has included the task of helping people distinguish the accurate historical images from the inaccurate, have been surprisingly uncritical in adopting the popular view of the Vaticans place in the world of espionage. When considering, for example, the Papacys role in such central events of the twentieth century as the two world wars, the rise and fall of totalitarian fascism and communism, the Holocaust, and the cold war, they have readily assumed that the Vatican, no less than the United States, the Soviet Union, or any other great power, deployed spies, covert operators, and all the other instruments of espionage and clandestine operations in support of its policies and interests. It is common for historians to speak knowingly of the Vatican intelligence service and for the especially bold to assert confidently that the pope is the best informed of the worlds leaders. This professional consensus is all the more surprising for the notable paucity of evidence to support it. Even the denizens of the secret world leave traces, no matter how faint, visible to sharp-eyed researchers seeking to confirm their presence or track their movements. No one, however, has tracked the rarest specimen of the secret world, the Vatican intelligence service. For all the claims and assumptions concerning papal intelligence, no one has set out systematically to confirm its existence, identify its characteristics, and describe its nature. It is a curious situation, as if a group of ornithologists sat about discussing the merits of a magnificent bird and describing its place in the ecosystem without anyone having actually observed the bird, discovered a nest, heard its call, or run across the smallest feather. A detached observer might be forgiven for suggesting that an expedition into the forest might not be a waste of time.

Intelligence is no longer, as the noted British diplomat Sir Alexander Cadogan asserted after the Second World War, the missing dimension of international history. In recent years intelligence history has become a lively field of historical study with all the accoutrements of an academic subject that has arrived: specialist journals and conferences, national and international professional associations, special lists at academic presses, and electronic discussion groups. Encouraged by the steady, if rather gradual, declassification of intelligence records, historians have been increasingly emboldened to investigate the role of intelligence and intelligence services in the formation and implementation of political, military, and economic policies. These investigations are enriching and in many cases challenging our understanding of historical personalities and events.

For all the growth and vitality in intelligence studies, most research and writing in the field has been characterized by certain biases of focus and periodization. Intelligence historians have tended to focus on the twentieth century, in particular the period 191445, in part because that period encompasses such historically significant and dramatic events as the two world wars, the rise and fall of empires and would-be empires, and the origins of the cold war; in part because the era witnessed the emergence and development in many countries of distinct intelligence organizations whose operations could be observed and described; and in part because archival records from the period exist in sufficient quantity and order to provide a documentary base for such descriptions. Historians have further narrowed their focus by concentrating on the intelligence experience of the great powers of the twentieth century. Within this initial concentration there has been a further disposition in favor of two particular powers: the United Kingdom and the United States. This geographic bias reflects the fact that until recently the majority of historians working in the field have been American or British. It also reflects the fact that, again until recently, American and British archival records have been more accessible than those of other countries.

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas