If you are not loyal to the ANC, you cant be loyal to anything else, even the Constitution.

JACOB ZUMA IS A MAN WHO WALKS in two worlds. As president of South Africa, he is tasked with upholding the principles that define the Constitution and embodying the values they are designed to engender. But, as an individual, a set of private impulses ranging from his religious beliefs, to his traditional African cultural convictions, to a populist and patriarchal attitude to power defines his world view; and many of these impulses run counter to the Bill of Rights. The result is an often-violent clash between his formal duties and more informal demagogic instincts. South Africas public debate is where that conflict plays itself out.

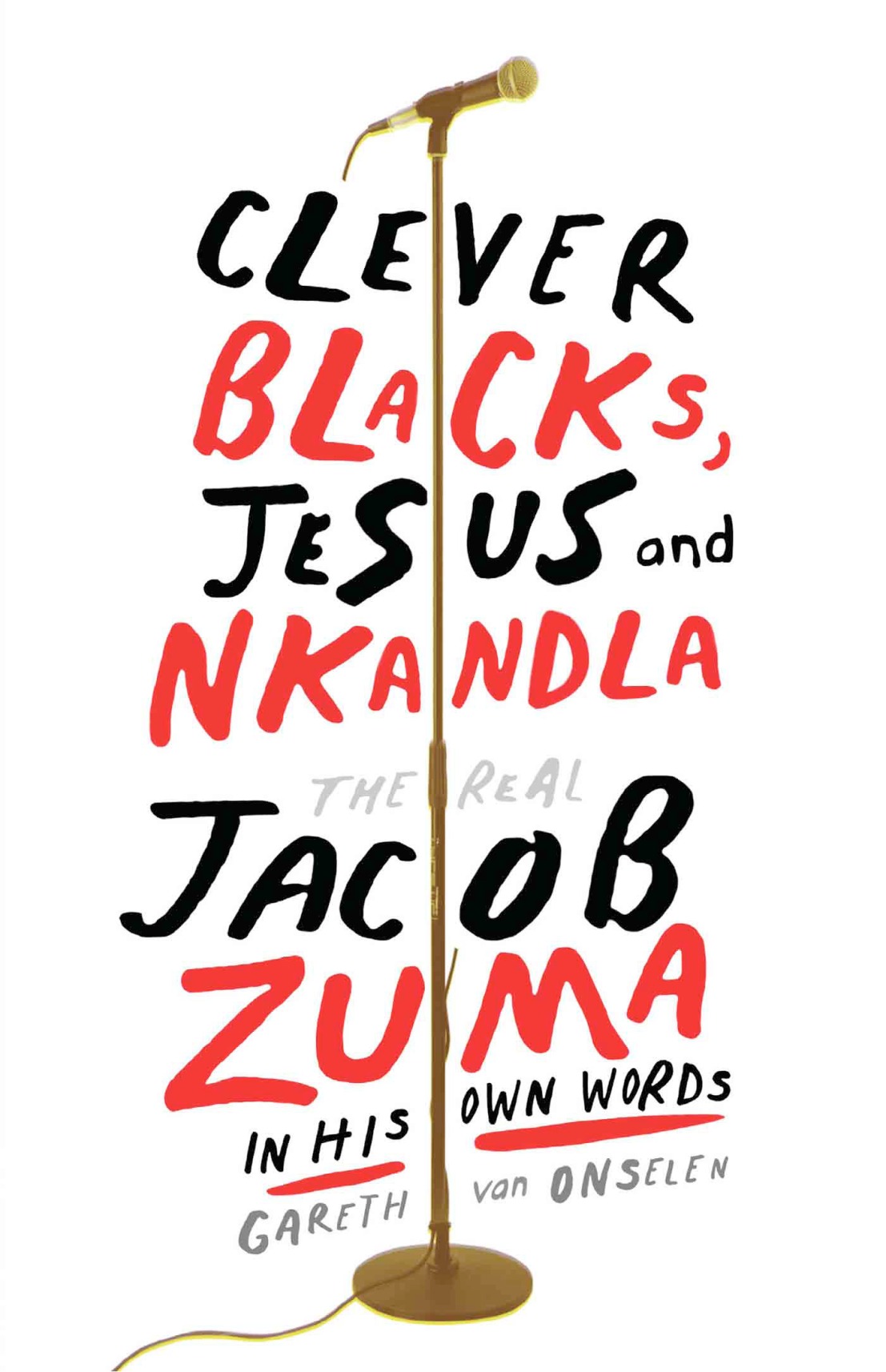

Acclaimed political journalist Gareth van Onselen has put together a comprehensive collection of Zumas most controversial - and often contradictory public statements. With some 350 quotes collected along ten themes that define Zumas personal beliefs, Clever Blacks, Jesus and Nkandla documents some of Zumas most notorious moments. It aims to serve as both an easy guide to Zumas personal philosophy and a reference point for some of the debates that have defined his political career. The quotes represent one of the fundamental faults lines that run through South African discourse today a society trapped between its Third World realities and its much-vaunted First World ambitions. In many ways, Zuma is the epicentre around which the subsequent debate has unfolded.

Gareth van Onselen obtained a masters degree in sociology at the University of the Witwatersrand before moving to Cape Town in 2001 and working for the Democratic Alliance in South Africas parliament. Among other things, he oversaw the partys research and communications as an executive director. He left the party in early 2013 to move into journalism. He now writes a daily column for Business Day and works as a senior reporter for the Sunday Times . Follow him on Twitter @GvanOnselen.

Clever Blacks, Jesus and Nkandla

The real Jacob Zuma in his own words

Gareth van Onselen

Jonathan Ball Publishers

Johannesburg & Cape Town

For Charles, Belinda, Jessica and Matthew, who helped to foster my love for words and meaning.

Introduction

The man who walks in two worlds

Imagine a man who supported virginity testing for girls; promoted deference of women before men as a sign of respect; questioned the constitutionality of bail; claimed that gay marriage was a disgrace before God; advocated prosecuting people even when the evidence against them was insufficient; believed the political party he represented was endorsed by God and that a vote against it would send you to hell; celebrated tyrants when they perverted democracy; advocated the beating of children in the name of discipline; defended Julius Malema as a future leader and Thabo Mbekis dissident views on HIV/Aids; argued that his party was more important than the Constitution; suggested that black people were defined by traditional African culture; believed that his party would govern until the end of days; regularly contradicted himself and reneged on his undertakings; paroled convicted criminals and defended his friendship with them; and regularly demonstrated an inability to take an ethical position on moral issues. A man who believed that all women should be married and that children were good training for womanhood; thought the Constitution granted minorities fewer rights than those in the majority; believed that pet dogs were un-African, as was the justice system, but encouraged people not to think like Africans in Africa; argued that prisons were unnecessary punishment and that crimes were better resolved through debate; was regularly corrected and reinterpreted by political handlers to make his gaffes more palatable; made unkept promises to appease whichever audience he was addressing; suggested that hair straightener was an attempt by black people to become white; benefited from R250 million in public money spent on upgrading his private house; had friends who would land their private plane at a National Key Point for their own convenience; thought a shower minimised the risk of contracting HIV/Aids; and blamed the media for an exaggerated and unfair public perception of his views.

You are imagining the president of South Africa. His name is Jacob Zuma.

These, some of the many controversies Jacob Zuma has stirred in South African politics over the past decade, are the subject of this book. Each quote speaks to a controversial position held by Zuma, whether an initial remark or a further illustration of a theme. The book is about the real Jacob Zuma because, it argues, these controversial statements far more so than the formal words that define his official duties as president reveal the primary impulses that underpin his private convictions.

What are those convictions? Zuma is a traditionalist, powerfully influenced by a set of cultural values that often run contrary to the Bill of Rights and the constitutional principles that underpin it. He is a patriarch, who describes women as subservient to men, there to be wives and mothers. He sees himself as a father figure, a chief, with respect and deference due to him in equal measure and patronage his to reward and withdraw. Those in his favour often act with impunity as a result. He is a bigot, dismissive of homosexuality, which he believes violates Gods law. He is a demagogue who plays different tunes to different audiences and who engenders the support of demagogues in return. His majoritarianism regularly clashes with the Constitution and many of its most central tenets, from the right to bail and the assumption of innocence before being proven guilty to individual liberties and rights. And his religiosity conflates church and state just as it elevates his party, the African National Congress, to divine status, beyond the reach of mortals and the free choice the Constitution grants them. Finally, he is a social conservative and a pragmatist who harbours an anti-democratic impulse about a number of issues.

His convictions are all-important, being the private backdrop to a public persona. They influence his decision-making, define his responses to problems and illustrate an agenda he is often constrained, by virtue of his constitutional obligations, from fully indulging. Understanding them allows one to go some way towards appreciating the view from his balcony.

Zuma is many other things, too. No doubt he has a number of virtues, but they have not come to define his public standing. Rather, it is his more controversial remarks that have left an indelible mark on South African public discourse. Indeed, his formal record is as bland and unremarkable as it is unexceptional. He will not be remembered as a visionary or philosopher king.

Zuma believes that much of the resultant criticism is unwarranted; that the media, which he believes often acts as an opposition party against him, is responsible for exaggerating, misrepresenting, taking his comments out of context and focusing only on the negative. But Zumas own words form the bulk of this book. You can judge for yourself whether, collectively, they paint the picture of a misunderstood president or a traditional demagogue out of sync with the demands of a modern democracy.

His issue with the media is not entirely without justification. Often his words are twisted. Zuma has never used the term clever blacks, for example. What he said was that some Africans, who become too clever, take a position, they become the most eloquent in criticising themselves about their own traditions and everything. Likewise, try as you might, you will find no direct quote in which Zuma says that having a pet dog is un-African. The original story in The Mercury reads: Spending money on buying a dog, taking it to the vet and for walks belonged to white culture and was not the African way, which was to focus on the family, President Jacob Zuma said in a speech in KwaZulu-Natal on Wednesday. That is as close as you will get.