Contents

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Secret History of Mac Gaming

With special thanks to the following superfriends for their generous support of this book

Joseph Agreda

Matt Alderman

Gui Ambros

Derek Balling

Clint LGR Basinger

Rocco Buffalino

Jan Burda

Keith Burke

Brian Christensen

Barry Cooper

Colin Cornaby

Matt Croydon

Cythera Guides (Seth Polsley)

Damien & Tika

Lee Dare

Alexis Delgado

Scott Densmore

Jon Duckworth

Rob Eberhardt

Paul Eremenko

Harley Faggetter

Cameron Friend

Peter Geddeis

David Gow

Joshua Grimes

Alex H

Drew Hamlin

Scott Herriman

Adam Howell

Tim Jenness

Keith Kaisershot

Tanara Kuranov

Matt Zebe Lee

Benjamin Mak

Preston Maness

Steve Marmon

Anthony Micari

Bobby Mohan

Simon Moss

Joerg Mueller-Kindt

Nadiim Dimo Nafei

Mike Nielsen

Dave Oshry

Justin Pauls

James Pederson

Fabrizio Pedrazzini

Matt Penna, III

Daniel G. Rego

Yannick Rochat

Rockey

Guido Rling

Sabrina Seerey

Max Silbiger

Scott Spencer

Jim Stirrup

Steve Streza

Michael S. Tashbook

Richard Thames

Jonathan Wrigley

Twenty-five-plus years ago aeons, on the timescale of the modern Internet we didnt have a single, simple, all-encompassing term to describe games published outside of conventional brick-and-mortar retail channels. There was no one generic name for independently made online-distributed games. Instead, there were several overlapping, unsatisfying terms.

For a period of the 1980s, we described it as the bedroom coder revolution. But that really only worked for the teenage whiz-kids who made their names with a few solo-created hits, and not the mortgaged 30-something garage tinkerers or the 20-something side hustlers. As a term it failed also to acknowledge the significant out-of-the-bedroom effort required to have a successful release going to computer shows and swap meets, running demonstrations for magazine editors, packing and duplicating games for mail orders, and so on. It made success sound simple, almost a matter of luck.

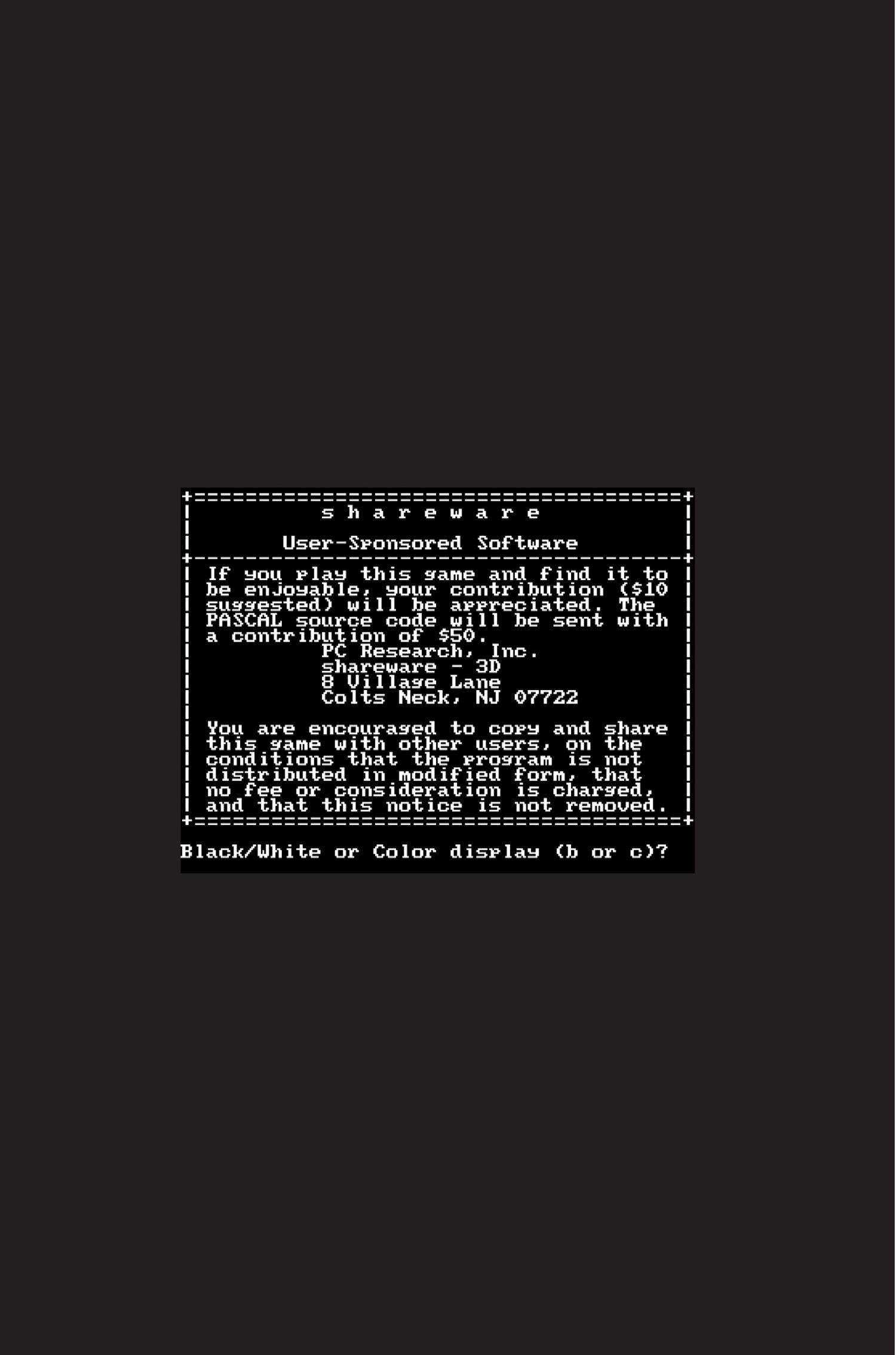

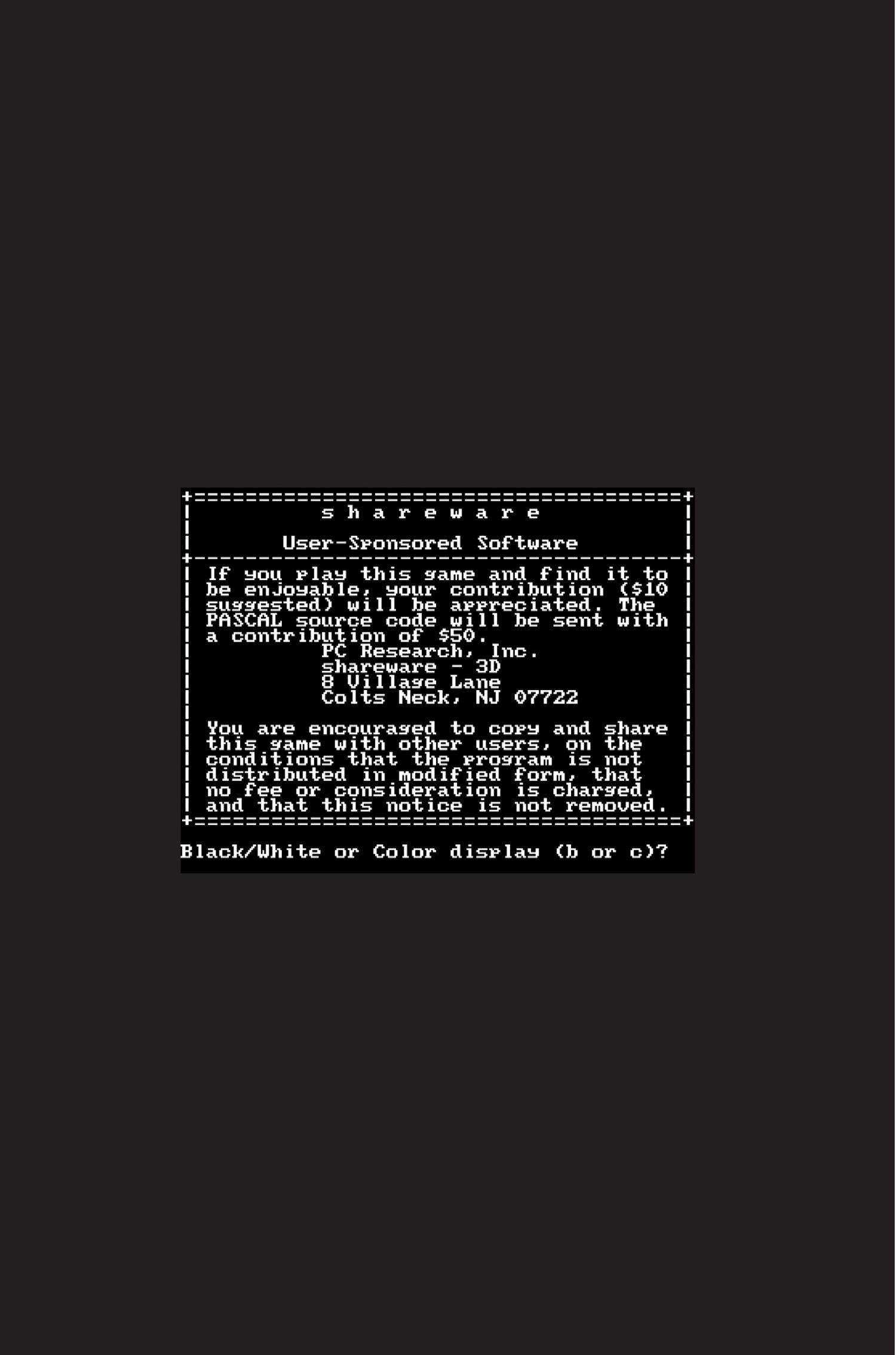

The music industry had indie or independent labels and the movie industry had independent film, but it would be years before anybody thought to apply the word to games. Instead, from the late 1980s through to the early 2000s, we described them primarily according to their distribution model: commercial games were sold in boxes at retail stores, budget games were low-cost commercial games, freeware games were free to play and distribute non-commercially (but the author retained their copyright), public-domain games were free games where the author released their copyright, and shareware games were well, there were a lot of shareware models, but essentially shareware games were free to try with a requested voluntary payment if you wanted to keep playing them.

(And often public domain was mistakenly used as a catch-all to describe the three non-commercial models all together.)

Shareware was the dominant of the three non-retail forms, and the one that best approximates what we call indie today. And it was a revolutionary concept the idea that you could download a program off the nascent Internet, try it, then pay if you liked it. Its proponents all said that one day all software would be sold this way; its detractors laughed in their face, astounded at their apparent naivety. But slowly, little by little, shareware proved itself not only viable but also (potentially) profitable before suddenly the term went extinct and the word indie took over.

This book is about how (and why) shareware rose to prominence and then disappeared from common vernacular, but its also about more than that. Its a book about people the everyday heroes who made this revolution happen. Some of them got rich; many of them didnt. All played their part. The meteoric rise of indie games would come later, but here we see something of a dress rehearsal a practice run wherein the kinks of independent marketing and distribution and sales and development of games could be smoothed out and tested with some of the best and worst games ever made (and lots of things in between).

In telling this story of a counter-cultural movement that changed both the games industry and the software business at large, Ive tried to provide a solid cross-section of what was happening. I wanted to explore not only the big sweeping changes and innovations that drove shareware to prominence but also the personal stories, the minor victories, and the disappointing failures. There were literally thousands of shareware games, so I never had any hope of covering everything but I hope I have at least provided a sense of what it was to be making and publishing games over the Internet back when the Internet was in its infancy (and before social media and microtransactions rewrote the rules again).

A note on sourcing

In the process of writing this book, I interviewed and consulted with several dozen people who were involved in the shareware scene. But memory is fallible, and many people were unavailable, dead, or couldnt be located, so I also turned to a raft of other sources to help me form as complete a picture of the history as I could. I pored over Usenet archives, dug up old and defunct websites in the Internet Archives Wayback Machine, consulted articles and interviews and databases published on extant websites, read old magazines and newspapers, bought and borrowed old books, searched for archived documents, and, of course, studied the games themselves. (Though unfortunately one critical resource the 1980s CompuServe forums appears to have perished completely, which left a gaping hole in the early shareware history.)

I tried as much as possible to keep track of all these sources and have compiled those records into a page on a website, which you can find at sharewareheroes.com/sources (also available on the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/shareware-heroes-bibliography). Many of my web-based sources are also linked to from a database I made to help me write this book, with listings of various key people, games, and companies from the shareware games scene. You can find that at ragic.com/sharewareheroes

Software used to be free. Back in the 1970s, its job was to sell computers. Occasionally it sold services. And even for the customers the people whose businesses and institutions bought computers software was considered a means to an end. It was a way to be more efficient, or more accurate. Or sometimes merely to further the needle to venture deeper into the vast unknown of what computers could accomplish.

Nobody thought about making money from their code. Computers cost millions of dollars. Who in their right mind would be willing to pay that kind of money, only to be stung again for the tools that made their computer useful? No, software was free for everyones benefit. And the most prolific users of computers, those same people who invariably wrote all the new computer programs, liked it that way.

![Mark J. P. Wolf (editor) - Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming [3 volumes]](/uploads/posts/book/279290/thumbs/mark-j-p-wolf-editor-encyclopedia-of-video.jpg)