Contents

Page List

Guide

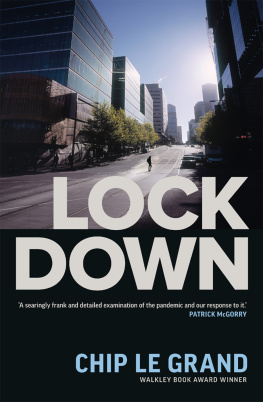

ABOUT THIS BOOK

Le Grand deftly takes us through the complexity, humanity, fear and, at times, irrationality of COVID-zero, and the unintended consequences we must never forget.

Catherine Bennett

A forensic and at times controversial analysis of Melbournes journey with COVID-19, peppered with the scientific, political and personal stories of a very difficult moment in time.

Sharon Lewin

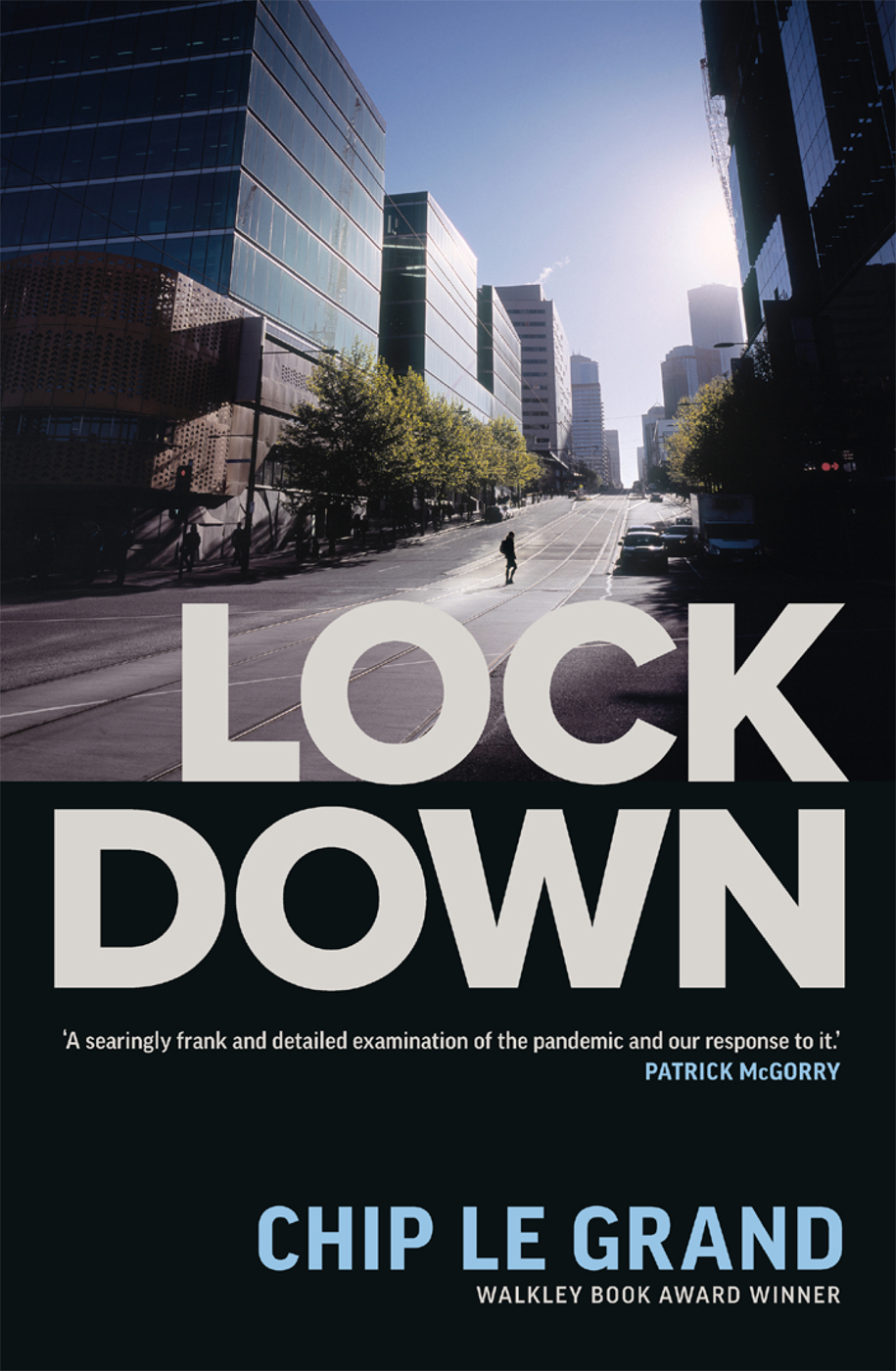

How does a city go from being the worlds most liveable to its most locked down? For 262 days, Melbourne was cocooned by stay-at-home orders. Businesses were forcibly closed, classrooms shuttered, and community and social life relegated to an impersonal online world.

To stop the spread of a virus, families were prevented from saying goodbye to dying loved ones, children were separated from their parents, and playground equipment was taped off like a crime scene. Through successive COVID winters, the state of Victoria was isolated from the rest of Australia and Melbourne from the rest of the state.

Our remarkable success was to eliminate the virusat least for a timeachieving something no other city had. We kept alive people who otherwise would have died, and prevented serious illness in others. As Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews declared when Melbourne emerged from its final, protracted quarantine: We have saved lives, we have kept people safe. But this came at a severe cost, one unlikely to be fully understood for years to come.

Lockdown is the story of Melbournes pandemic experience, an examination of the decisions taken in pursuit of COVID-zero, and what that meant for a city and its people.

CONTENTS

Lockdown

Copyright 2022 Chip Le Grand

All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australias Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher.

Monash University Publishing

Matheson Library Annexe

40 Exhibition Walk

Monash University

Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia

publishing.monash.edu

ISBN: 9781922633446 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781922633453 (pdf)

ISBN: 9781922633460 (epub)

Editor: Paul Smitz

Design: Philip Campbell Design

Typesetter: Cannon Typesetting

Proofreader: Gillian Armitage

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

CHAPTER 1 THIS IS AUSTRALIA

O N 4 JULY 2020, Melbourne became that city. Wed seen people snatched off streets and barricaded into apartments in Wuhan.

Wed seen heavily armed Carabinieri patrolling deserted villages in northern Italy. Wed assured ourselves such things could never happen here. Then they did, without warning or precedent. On a Saturday afternoon, at a time when kids are coming in from playing at the park and parents are starting to get dinner on the stove, images broadcast around the world showed hundreds of police surrounding high-rise housing commission buildings on the edge of central Melbourne. By 4 p.m., nearly 3000 people were effectively under house arrest, having committed no crime. That night, we were the city other people gawked at on their television screens, wondering what on earth was going on. Inside the towers, people stared down from their windows at a city they no longer recognised as their own.

Saeed Ali is sitting in the same place he was that day. Its a meeting room inside a disused warehouse in North Melbourne that a local Islamic community group, the Australian Muslim Social Services Agency (AMSSA), uses as a mosque and community drop-in centre.

Through the window, the Alfred Street commission flats rise above a post-industrial landscape now largely gentrified, with spruced-up workers cottages that used to house meat workers and their families selling for $1.5 million. Like many of the people who live in the flats, Ali was born in Somalia in East Africa. He fled the civil war there, heading west into Kenya and then travelling to Australia, on his own, when he was fourteen years old. He was twenty-one on the night that Victoria Police, carrying out detention orders issued by the states acting chief health officer, sealed off Alfred Street and eight other housing commission towers. People in the building, panicked and frightened, starting calling him, asking what was going on and what they should do.

Ali was one of only a few people who had known that an intervention of some kind was coming. An hour and a half earlier, hed been called to a meeting of local government and community members at the nearby North Melbourne Football Club and told of the governments intention to quarantine residents inside their flats to contain an outbreak of COVID-19, the novel coronavirus causing disease, death and community disruption around the world. No-one seemed to know how long the quarantine would last or how it would work. The meeting went for an hour and, as Ali recalls it, little was agreed to. By the time he got back to the AMSSA office, the familiar figure of Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews was on the television announcing a complete lockdown of the towers, including Alfred Street. As he made the announcement, the premier described it as the most challenging issue faced by his government during the pandemic. To this date, it also remains the most confronting. No government in Australia, before or since, has implemented such a draconian restriction of liberty to control the spread of the virus.

While Andrews was talking to the television cameras, Ali looked out of the window of the meeting room and across Boundary Road, and saw busloads of police arriving in the car park of the tower building. Hed expected to see police but imagined it would only take a handful of cops to instruct people to stay in their homes and answer their questions. Instead, it looked like a police response to a terror attack or a natural disaster. This stirred deep disquiet in communities that, since arriving in Australia from countries plagued by violent conflict, had never had reason to entirely trust Victoria Police. It was also closer to the truth than Ali or any of the tower residents understood. The lockdown, ordered by the states most senior public health official, was nominally overseen by Victorias then Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS, which in February 2021 was split into the Department of Health and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing). This is what you would expect in a public health intervention to contain an infectious disease. In practice, Victoria Police were running the show. Such was the haste with which the government decided to act that afternoon, a high-ranking Victoria Police officer was seconded to the health department to quickly throw together an operational plan. Mick Hermans is the assistant commissioner responsible for counterterrorism. He had spent the previous summer directing the evacuation of Victorian families cut off by bushfires. Now he was being asked to organise, within a matter of hours, something that had never before been attempted in Victoria. I think anywhere in the world would have struggled to respond to what we did there, says Chief Commissioner Shane Patton.

Victoria Police called it Operation Benessere, an Italian word which loosely translated means welfare. The tower residents didnt see it in these terms. Some of them hadnt done their weekly shopping and were nearly out of food when the police arrived and blocked the entrances to the towers. Some needed medicine. Others were caught short of critical items like nappies, sanitary pads, baby food and toilet paper. Some were caught on the wrong side of the police cordon and prevented from entering their own homesthey stayed with friends or family, and in some cases slept rough in their cars, until health authorities permitted them to return to their own beds. The government had locked people into a building where it knew the virus was circulating but hadnt yet provided them with masks or hand sanitiser to stop them from getting sick. It had promised them food and whatever support they needed, but as darkness fell over the towers, no-one seemed to know when or how these things would be delivered. The North Melbourne and Flemington commission flats, home to some of the states most disadvantaged people, were Jenga towers of anxiety.