There are newspaper publishers and editors in this country, apparently, who think that the freedom of the press was won for the sake of the press. Well, it wasnt. The freedom of the press was won for the sake of the people, and if the newspapers of this country are not prepared now to put aside party considerations and fight for that greater thing, the freedom of the individual, freedom for the ordinary man, then the day will come when the ordinary man will not fight for freedom of the press.

The Forgotten Man

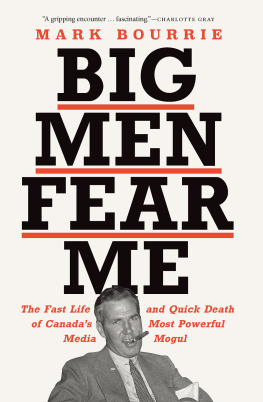

This is a book about a man who many people, including those at the centre of economic and political power, expected to be prime minister of Canada. Instead, he died mysteriously when he was just forty-seven years old. Youve probably never heard of George McCullagh, because hes been deliberately erased from Canadas history. Toronto columnist Robert Fulford called his biography one of the great unwritten books in Canadian history. Well, heres his biography. It will be up to you to decide whether its great.

So, who was George McCullagh and why should you care about him?

George McCullagh was a media rock star. He was the most powerful and dynamic man in Canadian publishing. He was also a giant in the nations sports world he was co-owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs and Toronto Argonauts, and had one of the best horse-race stables in Canada. McCullagh moved easily among the elites of the Western world and, though seen as a flawed man by those at the very top of Anglosphere governments, was feared and respected. A poor boy from London, Ontario, who dropped out of school in grade nine, McCullagh founded the Globe and Mail in the depth of the Great Depression, when he was just thirty-one years old. The Globe and the Mail and Empire had been around for decades before McCullagh came on the scene, but they were moribund newspapers that were dying of bad management. He hammered them together and made them the countrys most powerful political newspaper. And he deliberately gave the paper its strange name because its initials were still are GM, the same as his own.

McCullagh worked his way up from nothing by hiking the backroads of rural Ontario selling newspapers during the terrible recession that followed the end of the First World War and the 1918 flu pandemic. While he rose from those dusty roads to a reporting job in the newsroom of the Globe, he dragged his own ball and chain. As a young man he was an alcoholic. Booze masked the fact that he was also bipolar, and that turned out to be the thing that stopped him from becoming a national politician. In the end, it was probably mental illness that killed him.

McCullagh, with the help of William Wright Canadas richest man and a most bizarre multi-millionaire became a force in national politics. He advocated for one-party government in Ottawa and at Queens Park. And, for a while, he tried to convince Ontarios leaders to ditch democracy because partisanship got in the way of decision-making when Canada was struggling through an economic crisis. He used his media platform his newspaper and airtime that he bought on radio stations across Canada to start a national right-of-centre anti-democratic populist movement that peaked just before the Second World War. And when that war came, he fought news censorship, drove wedges that helped divide Canada when the country needed unity to fight Hitler, and helped make his best friend the premier of Ontario. When the war ended, he toured Europe and fired up hatred of the Soviets. Then he bought the Toronto Telegram and was the leader in Canadas greatest newspaper war.

McCullagh had a giant personality. Handsome, smart, funny, emotional, generous, and graced with tremendous social skills, he made friends among the elites of Canada, the United States, and Great Britain. He built an estate on the north end of Toronto that was home to some of Canadas best racehorses and show horses. But when things were going well, he would be struck down by depression and would sneak off to New York to see his psychiatrist. Dr. Robert Foster Kennedy was a man who believed mental illness was a mechanical and chemical problem, not something caused by spiritual or emotional distress. In those days, there was no mercy in Canadian society for anyone who needed psychiatric help, and McCullagh struggled alone, and in secret.

At the age of forty-seven, George McCullagh should have been making a move into national politics. The way was open for him to be leader of the federal Conservative Party when his friend George Drew was finished taking his turn. Instead, McCullagh died, almost certainly by suicide, after years of silent suffering and brutal psychiatric treatments. The stigma of his death is one of the reasons youve probably never heard of him. Soon after the massive crowds dispersed from his wake and his funeral, George McCullaghs name was removed from the masthead of the newspapers he owned. His picture came down from the wall of the Globe and Mails boardroom. Some years later, his widow, angry and bitter, burned all of his papers, leaving scorched earth for any biographer who tried to tell McCullaghs story.

The Canada of McCullaghs era has passed. Back then, Toronto was the second-largest city in Canada, a second-rate town in which Britishness was valued and a small Anglo-Protestant elite made the rules. It was a city of appalling class divides in which racial minorities, Jews, Roman Catholics, and anyone else who didnt meet the criteria for admission to the elites of Rosedale and Forest Hill were not true citizens. They were barred from the best jobs in the public and private sector, and their role was to work, serve, show up when Torontos financial and political elite needed a crowd, and, otherwise, stay silent.

This version of Toronto is gone now, and frankly, its not a huge loss. Its the Toronto where I was born, and it was the city where I had my first full-time newspaper job. Like McCullagh, I loved newspapers, and this is my gift back to an industry that made the first decades of my working life a delight. This is a love letter but also a kiss goodbye to an industry that is nearly gone. In the early 1980s, Canadians started turning away from newspapers. The decline started almost two decades before the advent of the internet. Now, Canadian newspapers are struggling. Canadas largest chain is owned by an American hedge fund, which has asset-stripped its newspapers to the point where their reporting staffs are no longer able to cover basic news in their communities. Many of their staff members are dedicated journalists who try to inform readers, but newspapers cannot cut their way to journalistic or financial success, no matter how deep those cuts may be. A supposedly temporary government bailout just papers over the systemic problems and delays the inevitable reckoning and restructuring. All of the rest of Canadas English-language dailies are privately held, and the hedge fund mentality of undercapitalization and poor local service afflicts most of those papers, too.

George McCullaghs Canada has also passed into history. It was a land where great veins of gold were waiting to be discovered by people willing to trudge through the boreal forests of Ontario in 45 weather, where a man with no education could become the most important publisher in Canada, where politicians had no problem inciting mobs in the countrys arenas and city parks, rather than through Twitter and Facebook. It was also a country where a bright kid with unlimited ambition could decide to create a great corporation, find the capital to do it, and leave the country with a great media institution that continued to be relevant for fifty years after his death.