ALSO BY KATE BUFORD

Burt Lancaster: An American Life

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2010 by Kate Buford

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Buford, Kate.

Native American son : the life and sporting legend of Jim Thorpe / Kate Buford.

p. cm.

Borzoi Book.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59429-7

1. Thorpe, Jim, 18871953. 2. AthletesUnited StatesBiography. 3. Indian athletesUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

Gv697.T5.B84 2010

796.092dc22

[B] 2010012815

v3.1_r4

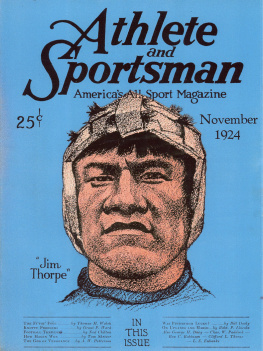

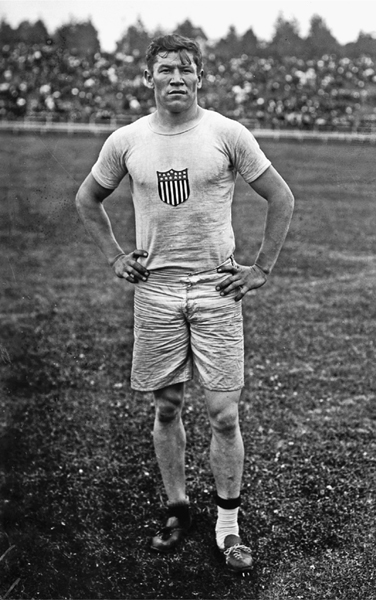

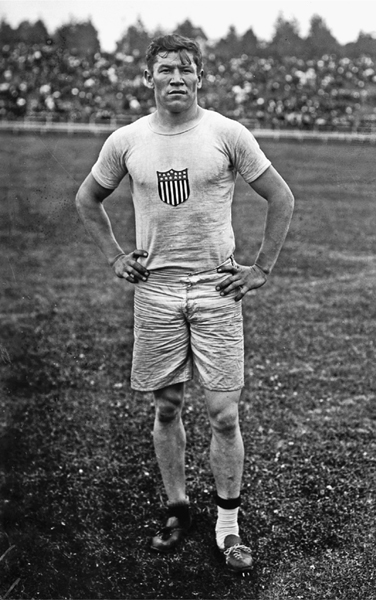

FRONTISPIECE

Jim Thorpe, Fifth Olympiad, Stockholm, July 1912

T HERE IS a strikingly modern look to this photograph of Jim, dressed in the field uniform of the 1912 U.S. Olympic team. The T-shirt is now so familiar and ubiquitous a piece of street clothing it is easy to forget that it was rare in 1912. Rumpled, sweaty, dirty, and exhausted, he is the athlete in temporary repose.

To Lucy and Will

Contents

PART I

THE RULES OF THE GAME

PART II

THE PROFESSIONAL

PART III

LIFE AFTER SPORTS

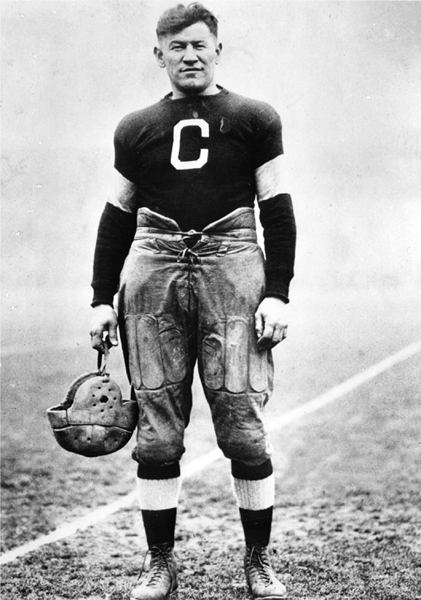

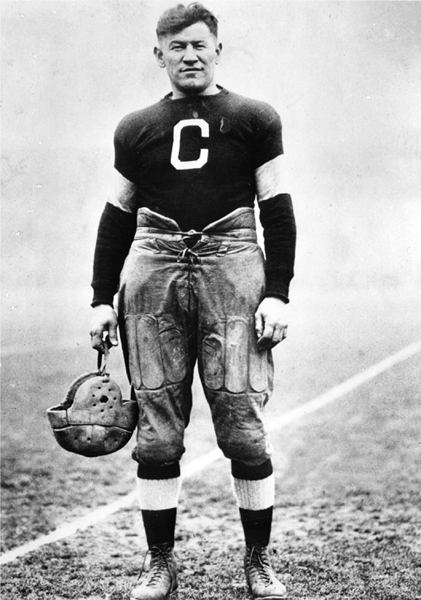

Jim Thorpe with the Canton Bulldogs, c. 1920, Canton, Ohio

I T IS LATE on a cold afternoon in November, about seven years since his world collapsed. His name was struck from the official record of the 1912 Olympics, his gold medals stripped from him. For playing minor league professional baseball for two summers he was expelled from the elitist stratum of Olympic sports, branded a pariah among simon-pure amateurs. The shock remains in his head, a nightmare that never ends. Though hardly an innocent, he would never understand exactly what he did wrong.

He radiates sadness, though theres a hint of a good-natured smile. His stance seems to say that a photograph is beside the point; his life is about movement, not still poses for posterity. The sweater is scratchy and stiff and smells like sweat. The big white C stands for the Canton, Ohio, Bulldogs, a rough, early professional football team. His leather pants are crude and loose and held up by laces tied together at the waist. His body is solid and compact. He has big shoulders, hips thrust slightly forward, feet pointed straight ahead like, as whites said back then, an Indians. The top of the face also triggers old white preconceptions of what Indians are supposed to look like: cheekbones like Mount Rushmore and eyes that squint with the all-seeing gaze of the warrior, the noble savage.

He is the Indian transposed to the playing field of sport, and its a mythic transfer at that: Jim Thorpe, consumed by sports, just as they now consume us, was the first world-class celebrity sports figure and perhaps the finest all-around athlete America ever produced. His example prompted countless collegiate teams to choose the Indian as their mascot for the game that was seen, when he played, as a symbolic reenactment of the territorial wars that had so recently won the American land for the whites.

A mixed-blood Indian, partially white, he grew up on the often lawless, wide-open frontier of Oklahoma. He would internalize that chaos to make his own perpetual frontier, a no-mans-land of conflicting identities and permanent unrest that found expressionand reliefon the playing field of sport.

Prologue

W hen Jim Thorpe was named the best football player of the half century on January 25, 1950, by an Associated Press poll of 393 national sportswriters and radio broadcasters, there was the usual grousing about comparing Jim was a man, and the rest are children. I mean that Jim Thorpe was monumental, Brobdingnagian, colossal and perfect; the others are only shadows in his wake.

The next day, when Jesse Owens was named the top track and field athlete with 201 votes and Jim was the runner-up with 74, Jim, sixty-two, spoke at a testimonial dinner in his honor in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He kept the audience laughing as he reminisced happily about his days at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. At a sportswriters banquet in nearby Harrisburg soon thereafter, the crowd rose when he was introduced and applauded him for five minutes. Overcome at the warmth and welcome extended to him by the people who had seen him at his best, he had tears in his eyes. He had been stoic for so long, and the sadness, anger, and helplessness that had been festering for years now flooded over him.

The AP polls continued into February, recognizing the greatest achiever in each major sport, until Sunday, February 12, when [t]he Sac and Fox Indian is almost a legend now. Unlike most legends, though, he never needed any fictional embroidery to add luster to his accomplishments. The truth was breathtaking enough and hard to believe, because it seems inconceivable that any one man could be so overwhelmingly endowed by nature with all the skills and talents the Indian had in superabundance.

The annulment of Thorpes Olympic performance in 1912 had fueled a grassroots hunger for vindication. He had become a folk hero, one of the last before what Swedish sports historian Leif Yttergren called the massive media exposure and commercialization of the celebrity culture that took root in the 1920s. Taciturn, poor, relatively uneducated, clearly ill at ease at public events, the victim of personal tragedy and misfortune self-inflicted and accidental, a man who rarely had peace, Thorpe was someone with whom all people could identify.

While some of his life story is certainly pegged to larger developments in Indian history and U.S. policy, particularly in his early years, it is impossible to fit him into a preconceived pattern. He was sui generis, His life is defined in large part by the man people expected him to be, good and bad, as well as the man he really was. His unique fame as the central figure at the dawn of American and international popular sports is clouded by the question of how much he was the victim of prejudice and how much he was his own worst enemy.

A gentle person, intelligent and funny, with many flaws, Jim Thorpe was not a complicated man. But what happened to him was.

The term Indian is used in this narrative because it is the word the Thorpe family uses to describe themselves. Similarly, the term Sac will be used instead of the more correct Sauk because that was the name generally used in written records before and during Jim Thorpes lifetime.

PART I

The Rules of the Game

This democracy, this land of freedom and equality and pursuit of happinessit could have worked! There was something to it, after all!! It didnt have to turn into a greedy free-for-all! We didnt have to make a mess of it and the continent and ourselves! For a moment I could imagine the past rewritten, wars unfought, the buffalo and the Indians undestroyed, the prairie unplundered. Maybe history did not absolutely have to turn out the way it did