Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

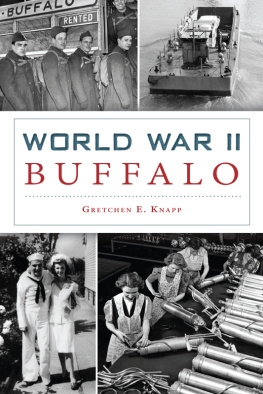

Copyright 2017 by Gretchen Knapp

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.376.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017948513

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.695.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my late mother and father, Gert and Fred Knapp, with love

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks are owed to the archivists and librarians of the National Archives and Records Administration (William Creech and Richard Boylan), Library of Congress Manuscript Division, New York State Archives (Daniel Linke and William Gorman), New York State Library, University at Buffalo Archives (William Offhaus), Buffalo State University Archives, Buffalo History Museum (Cynthia Van Ness), Buffalo and Erie County Public Library (William Loos), Canisius College Archives, Fort Niagara, Niagara Falls Public Library (Don Loker), Historical Society of the Tonawandas (Ned Schimminger and Skip Johnson), International Institute of Buffalo, Immigration History Research Center and Social Welfare History Archives (University of Minnesota), National Board of the Young Womens Christian Association, New York State Military Museum, Sisters of St. Francis at Stella Niagara (Mary Serbacki, OSF), the Minerva Center, Young Mens Christian Association and the United States Holocaust History Museum.

The interlibrary loan wizards at the University at Buffalo, Eastern Illinois University and Illinois State University deserve high praise.

I am greatly indebted to the late Dr. Karl Hartzell, the New York state historian whose conscientious collecting of documents and photographs during World War II made this work possible.

Thank you very much to Rosemary Dold, Marianne Ferber, Emanuel Manny Fried, Jay Garner, Paula Kaleta, Carol Pujolas, Karen Simpson and Joan Busch Staley for sharing their remembrances and pointing me to more information. Thomas Bolze, Kate Butler, Megan Cavitt, Mary Clare Dolata, Amber Finck, Paula Kaleta, Ann Marie Przybyl, Michele Raupp, Crystal Robinson, Leo Schpilkes, Paula Wager and Vicki Walsh contributed valuable suggestions and unflagging support. I am most appreciative to Margaret Abels (Nardin Academy), Judy Einach, Timothy McCarthy (Nichols School), the Pujolas family and Carol Schmeidler for sharing their private collections.

To my husband, Angelo Capparella, who encouraged me throughout the creative process, thank you for applying a keen eye to my work and practicing endless patience.

INTRODUCTION

Under a grassy rise in Elmlawn Cemetery next to my paternal familys plot lies Private First Class Francis N. Dempfle, U.S. Army. He died on December 13, 1944, at age twenty-one. His was the first burial in the Field of Honor.

Once a month, Mom, Dad and I put flowers on my grandparents grave and gave a respectful nod to Great-Aunt Ella. I wandered to look at Private Dempfles grave, as I always did.

He died during the war, said my father, putting his hand on my shoulder. I was nine, and the only war I knew was in Vietnam, where my cousin served. We spoke with his family once. Very sad.

Dempfle enlisted in Buffalo on February 12, 1943. He was a member of the 2nd Platoon, Company K, 311th Infantry, 78th Division, known as the Lightning Division. The 78th landed in France ready for combat on November 22, 1944, and entered the Hurtgen forest in Germany on December 10. Three days later, Dempfle was dead.

James Coopers father served with Francis. On the day he disappeared, Francis was making his way back to the company command post from an engagement in the forest. He never made it back, and no one knew what had happened to him.

Later, I discovered that the Hurtgen forest battles were among the deadliest and most senseless during the war in Europe. His remains were discovered in Germany in 1976 and returned to the United States for burial near Buffalo. The Germans erected a monument in the forest to mark the location where he and three other missing soldiers were found. The Department of War awarded him the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star Medal.

Until 1976, I was visiting an empty grave.

I knew my father enlisted in the U.S. Navy days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. So did his best friend, Bruce Stark, and my uncle Edward McCarthy. Uncle Arnold Dold served in the U.S. Army in Germany during the war and later in its occupation. Aunt Rose flew a plane that she co-owned with other women pilots in the Civil Air Patrol. My mother and her sister Geraldine and their friends and relatives worked at Curtiss-Wright. Every male neighbor, teacher or family friend of a certain age was a veteran. (I didnt meet a female veteran until 1992.) They were everyday Americans who had done extraordinary things.

That was the first reason I became interested in World War II.

My parents celebrated their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary when I was twelve. They took me along to Hawaii to visit Pearl Harbor, where my father had been posted, serving on aircraft bound for Midway. Hotels had replaced command posts, but the outline of the wars impact was visible through my fathers eyes. We visited the newly built USS Arizona memorial, the final resting place for the ships 1,177 crewmen, who lost their lives due to the surprise Japanese attack. The pale flower wreaths bobbed in the waters on each side of the long white structure in memory of the fallen.

And that was the second reason for my interest in the war.

In 2011, I was cleaning out my childhood home after my parents passed away and found the red laundry washboard that had served as a mirror in the back hall. In gold letters, the date July 31, 1943, was painted across the top. It was the day that they were married.

I half-remembered the story. Every weekday, my mother took the streetcar from Thompson Street to work at Farrell-Birmingham, a defense plant that manufactured gears for the navy. Before my father, a navy aviation machinists mate first class, shipped out to the Pacific, he sent for her. In my mind, I see her looking around in amazement at the bustling crowds in the Central Terminal, clutching a small suitcase that held her handmade wedding suit. I can only imagine the fortitude needed for a young woman who had never been outside Buffalo to endure the long train ride to the naval base in Jacksonville, Florida.

President Roosevelts own chaplain, an Episcopal priest, performed the wedding service. A married couple my father knew stood up for them in the bases little chapel. After a brief honeymoon in St. Augustine, where Ponce de Leon allegedly discovered the Fountain of Youth, both drank from a battered tin cup. Mom returned to Buffalo to work as a salvage manager at Curtiss-Wright. Dad came back after three years and ten months to attend college in Oswego, thanks to the G.I. Bill. The old-fashioned red laundry washboard now resides in my house.

Next page