First published in 2021 by Rough Trade Books

Design by Craig Oldham

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means electronically, photocopy, recording or otherwise without the permission of the copyright owners. Claire Ratinon & Sam Ayre, 2021.

The right of Claire Ratinon & Sam Ayre to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Sections 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Print ISBN 9781912722990

eISBN 9781914236037

Claire Ratinon & Sam Ayre

Horticultural Appropriation

Why horticulture needs decolonising:

A conversation in the gardens of West Dean

Rough Trade Books

x Garden Museum

SPRING 2021

Introduction

Claire Ratinon and Sam Ayre were asked to take up the West Dean Colleges Garden Residency for 2020/21 after Ratinon was invited to share her experiences and considerations on the politics of growing food as part of the perma/culture lecture series at the college. As part of their residency, Ratinon and Ayre were interested in furthering the conversation around colonialism and horticulture by connecting it to the interrogation of how the archive and collection of artefacts at West Dean are implicated in the issues associated with Britains colonial project.

In 2019, the Collections Team at West Dean began the Whose Heritage? project to re-evaluate how the collections are presented by intentionally disrupting the euro-centric perspective that has historically informed the curation and questioning the power structures of colonial histories in order to deconstruct ideas of privilege and the white gaze. Both the College and the Gardens belong to the Edward James Foundation, which aims to provide high quality teaching in the arts and conservation in line with the life of the poet and artist Edward James, who used the estate and his inherited wealth to sponsor artistic expression in all its forms.

This pamphlet is a conversation that took place during their time at West Dean and, alongside a number of Ayres drawings informed by the West Dean archives, explores what horticulture might learn from the art and museum worlds attempts to decolonise their collections and practices.

Sam: In 2012, I started running my first after-school club at a secondary school in Hackney. I asked this group of teenagers, What do you know about art? and a girl replied, all artists look like you. I was like, ugh! So I scrapped what I had planned and instead we spent our time together engaging with the work of artists who dont look or sound like me. The club was called The Contemporary Art Society and the kids decided to add the addendum: Non-Dead, Non-White, Non-Male.

Claire: I think it was around the same time when I was finally finding the confidence to have real conversations about race and gender and identity although my understanding of those subjects as viewed through a decolonial lens has only come about in the last few years. Thats what those kids were doing, right? Challenging you to decolonise the art curriculum?

Sam: I think initially what started for them as a challenging of authority transformed into a decolonial practice. And I wasnt aware at the time that it could be considered as such but looking back, thats what it was. I think the art world knows that they need to be doing this, they know they ought to decolonise their collections and their systems and their structures. They need to look up from the pages that they have read and re-read, taught and taught again, the way in which they make determinations on what is art and what isnt artthat all needs disrupting. Its just not a priority for most institutions and most people.

Claire: Well, I think that changed somewhat in 2020 with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement that has led to all manner of organisations and companies and institutions being held accountable for the ways in which they operate, what they represent, what they produce and how, as well as who they serve and who they exclude. For me, its been quite incredible to see what only a year ago felt like a niche critique of my industry become central to the conversations amongst my peers. Agriculture and horticulture are fertile grounds for deconstructing the coloniality that is foundational to their practices, plants and mindsets.

Sam: Hahaha, fertile ground! I like that these metaphors of literal nature growing are used so often now in both art and wider culture to describe peoples ideas, processes and careers. This artist has blossomed etc. Art about nature appears to be very on trend right now. I spoke to an art critic friend of mine recently who was worried that I was making mushroom art because I sent him a picture of some cool-looking fungi I saw on a log. I assured him that I had nothing new to add to that area of art-making!

Claire: Well yes, nature overflows with metaphor! I dont know whether theres a good one for decolonisation though. Maybe how certain fungi can be deployed to clean up pollutants and radioactive waste?

: Mycoremediation is the practice of using mycelium to sequester contaminants, clean up radioactive waste and remediate radiation. For example, the Ocean Blue project have grown oyster mushrooms on river banks to restore contaminated aquatic habitats where they are based in Corvallis, Oregon.

Sam: Yeah, very cool. I also think that people are less ready to accept metaphors about decolonisation as they feel so attacked by these conversations, ideas and desire for change.

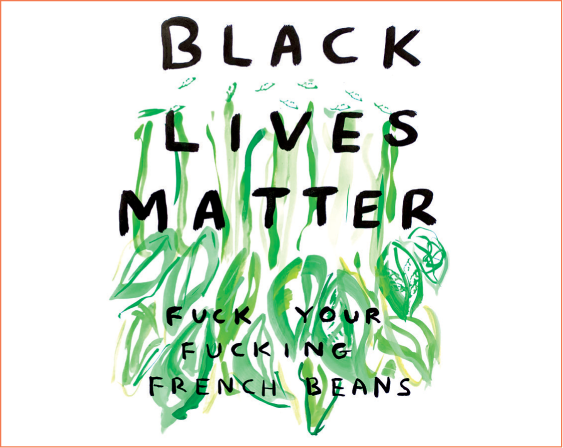

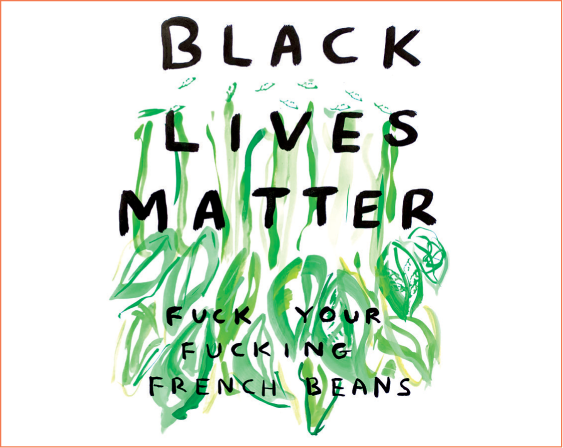

Claire: Ive certainly seen that reaction amongst gardeners and horticulturalists who prefer to believe that plants and flowers should remain in the realm of beauty and skilful execution and not be dragged into conversations that politicise them. If it hadnt been for the choices made by certain gardeners and horticultural institutions to ignore the racial reckoning that was taking place by continuing to post their trite gardening content during a week that asked for a quietening out of respect, I wouldnt have lost my rag and said fuck your fucking french beans. But that phrase led to the birth of our first collaboration in the painting you created of it. The irony is that no aspect of horticulture can be extricated from colonialism as far as Im concerned. The way in which plants were discovered, collected, transported, commodified and weaponised was all part of the colonial project and their legacies are growing in our gardens to this day. The problem is, this information, this history, is not widely discussed. You cant find it on the plant labels in the garden centre. When your work or hobby is to grow beautiful flowers, theres no obvious impetus driving you to delve into the history of the plants you grow, or to care about how they got to your garden. Most people think of history as a string of stories from long ago with no relevance to the present day.

Sam: I think, quite often, mythologised notions of history are fetishised in a bid to resist societal change. Even though reconsidering history is not about rewriting it, its about shedding light on it and considering the histories that have been erased, ignored and remain untold. Artists do this all the time so it seems strange to me why some institutions and individuals are so resistant to it. When we met Sarah Hugheswho invited us to West Deanit was clear that what brought us together was a shared preoccupation with what we can learn from bringing a decolonial lens to our workand as a curator, Sarah is examining the way in which colonialism permeates the collection and what can be done to address the ways that continue to be offensive and disrespectful to the artefacts and objects as well as the communities they were taken from.

Next page