CAMBRIDGE COLLEGE

GARDENS

TIM RICHARDSON

PHOTOGRAPHS BY CLIVE BOURSNELL AND MARCUS HARPUR

INTRODUCTION

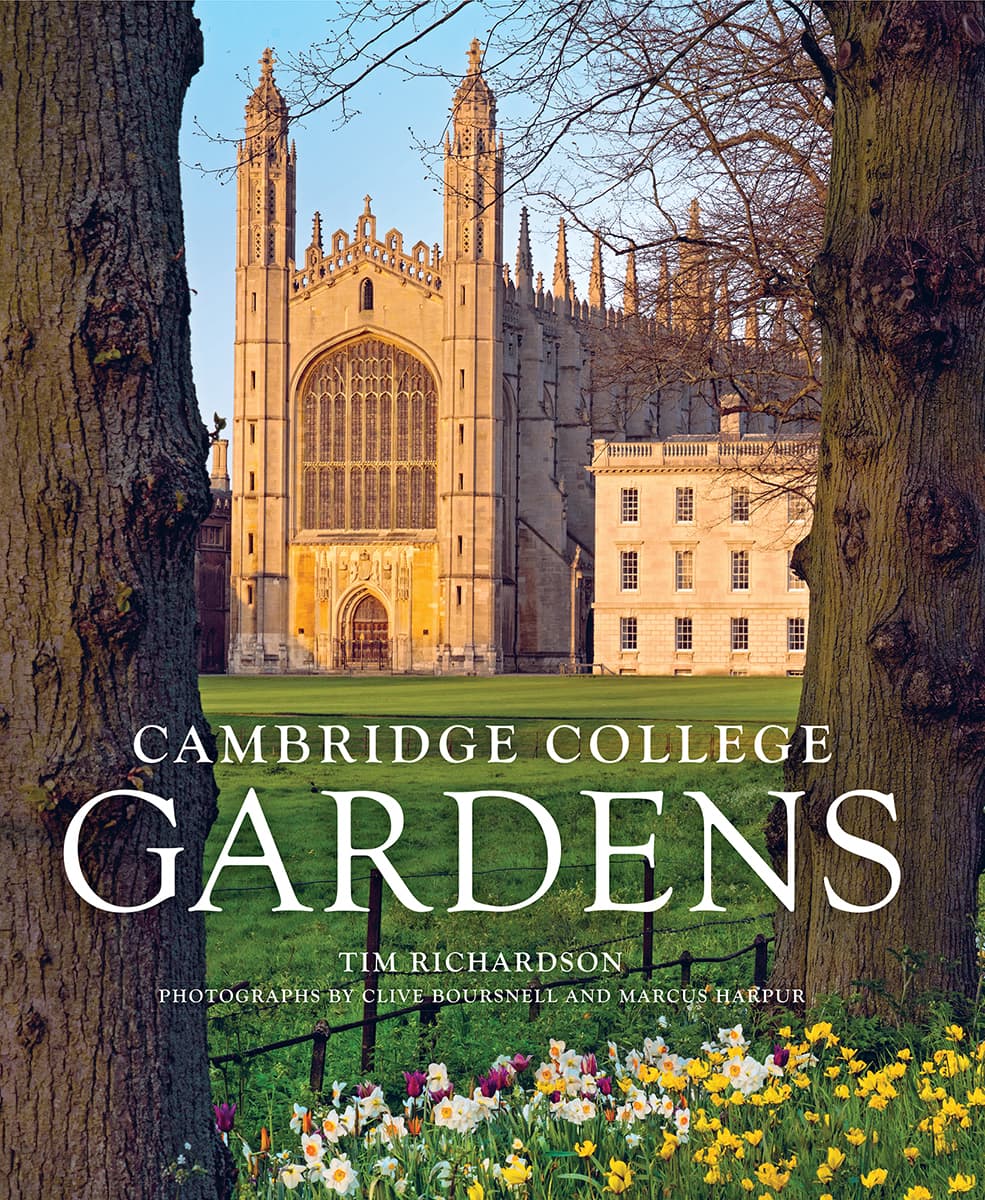

C AMBRIDGE IS RENOWNED INTERNATIONALLY AS a centre of learning, with a special historical bias towards the sciences and mathematics. But it is also the most beautiful university city in the world. (Arguably, of course because argue is what universities do.) That beauty derives largely from the visual appearance and palpable atmosphere of the 31 colleges which constitute the university today a beauty arising from the architecture of their courts, chapels, halls and libraries, certainly, but also by dint of the various gardens and landscape settings in which they sit. The area of meadows and gardens behind or to the west of the colleges on the River Cam is known as the Backs, and is perhaps the most outstanding aesthetic feature of the university, especially if one includes great buildings such as Kings College Chapel in the scenographic whole. A walk along the Backs was eulogised by an American visitor, William Everett, writing in his On the Cam in 1865:

There is nothing of the kind lovelier in England. The velvet turf, the ancestral elms and hoary lindens, the long vistas of the ancient avenues, the quiet river, its shelving banks filled with loiterers, its waters studded with a scene of gay boats, and crossed by light, graceful stone bridges; the old halls of grey or red or yellow rising here and there, the windows peeping out from among the trees, and the openings into old court-yards, with their presage of monastic ease and learning, the lofty pinnacles of Kings Chapel oertopping all

The beauty of the Backs as a landscape feature has been appreciated since the early 18th century, while the garden areas of the Cambridge colleges have perhaps received rather less notice. Yet as we shall see, gardens have been an extremely important element in the life of the university. Walking through the colleges, it rapidly becomes apparent that buildings and gardens are almost indivisible if one is open to appreciating the setting as a whole.

Since the medieval period the college gardens have incorporated spaces for leisure, food production and scholarly meditation, all in the safely cocooned atmosphere of a sociable community. And they still do with kitchen gardens and allotment areas once again coming to the fore at a number of colleges, and prospective students citing the attractiveness of the gardens and grounds as a major reason for selecting a college. The lucrative out-of-term conference business, which currently keeps many of the colleges financially afloat, is another impetus for investment in the quality of the surroundings. And there is now a timely sense of environmental responsibility, including the conservation of plants, insects and animals, as well as the benefits to peoples physical and mental well-being that a garden provides. Gone are the days when a colleges front court might well have been a muddy quagmire surrounded by a gravel path, with thick forests of ivy festooning the crumbling walls. Today, every college in Cambridge presents a smart appearance to the world, and in several cases the garden teams are cherished and well-resourced.

Cambridge is haunted by the spectre of another university. It was founded just a few years earlier but established itself with far more alacrity and remained dominant until the 16th century. As a result, Cambridge has developed a habit of comparing itself with Oxford. It is true that the colleges of both universities appear similar. But there are a number of salient differences in their layout and visual tone.

It is well attested that Cambridge University came into being because a group of scholars left Oxford in 1209 following a series of violent altercations with the townspeople, and the execution of two Oxford scholars. The story goes that a woman possibly a prostitute was shot and killed with an arrow by an Oxford scholar. Quite how and in what circumstances an Oxford student might shoot a prostitute with a bow and arrow is unclear (it is possible he stabbed her at close range, since arrows were sometimes used as hand-weapons). A vigilante band of townsmen hanged not the perpetrator but two (possibly three) of his fellow students, by way of revenge. This summary justice outraged ecclesiastical law, since the students were de facto clerics and not subject to civil authorities. If the story is true and it came largely from Roger of Wendover, who is not a particularly reliable source it is not altogether surprising that a number of Oxford students wanted to leave the city at this point.

At Jesus College, overgrown Victorian yew topiaries add immense character. A Parrotia persica has been planted as a focal point.

The old Cambridge tradition of vine-growing is continued in Trinity Halls Avery Court.

One group decamped to Paris, which had a greater scholarly reputation than Oxford at that time, while others went to Reading and Northampton, the latter already established as a centre of learning. (Most of those scholars returned to Oxford between five and ten years later when the pope had intervened and the troubles died down.)

Cambridge was not perhaps an obvious choice as an alternative safe haven for scholarly refugees. It had no existing culture of scholarship, bar a few grammarians who offered a basic education to the wealthier sons of the town. It had long been a strategic staging-post, with its Norman castle on the site of an Iron Age fort, and also offered a riverine trading link with the Hanseatic port of Kings Lynn to the north (it was the invading Danes who had established Cambridge as an inland port). Several monastic orders had founded priories in the town, institutions which also undertook the training of young clergymen; the oldest, Barnwell Priory, was constructed north-east of the city in 1112, while the Benedictine nunnery which later became Jesus College was founded in 1133. But despite its situation as a gateway to the east of England and the Midlands, Cambridge had not grown into a large town, and its strategic importance had faded somewhat by the 13th century. Natural obstacles, including the thick forests of Essex, meant that there was no direct link by road with London. The river trade remained important right up until the mid 19th century, but essentially Cambridge was for many centuries a small market town it did not even have a bank branch until 1780 overtopped by a ruined castle.

It is now thought likely that Cambridge was chosen by this group of fleeing Oxford scholars chiefly because a number of them originally hailed from that part of the country. John Grim, a Cambridge man, had been the master of the schools in the centre of Oxford (in the area where the Radcliffe Camera stands today), which was the most senior position in the university prior to the creation of the chancellorship in about 1214. It is believed that Grim led his colleagues to his home town, where due to his local connections they would have had a better chance of obtaining favourable rates for the rent of the townhouses used as hostels for students, which the masters rented and then sublet out to their charges. (The collegiate situation which prevails today is only a somewhat more developed version of this system.) Grim was not the only man in this group to be associated with the east of England: his confederates in the migration included at least three masters known by town names of the eastern counties one of them, for example, was Adam of Horningsea (a village in Cambridgeshire).