VISIT...

Table of Contents

To my Mother

Note to the 2010 edition

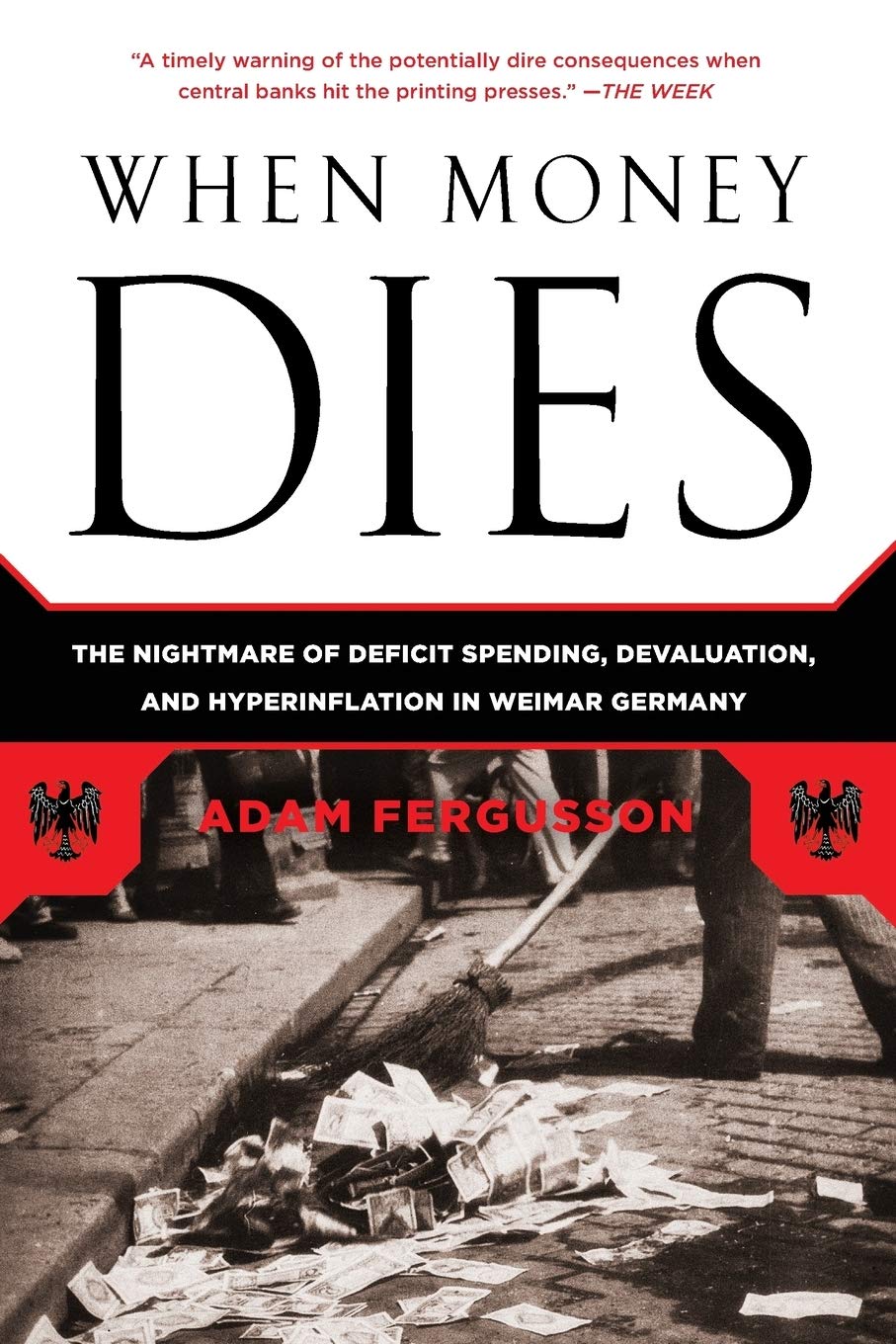

When this book was first published in 1975, as its prologue observes, comparison of contemporary prices and values with those of half a century earlier was of limited advantage. Thirty-five years on, when currencies have continually merged, diverged, depreciated or disappeared, and when costs and wages have risen and fallen with so little uniformity, the exercise sheds no more light. True, statisticians have reckoned that the pound sterling of 1923 would do the job of 623 today; and that the 1923 dollar might now buy $220 worth of goods and services. However, rather than be burdened with interesting but highly speculative comparative calculations, the reader is invited to accept the text as it was written.

In dealing with the stupendous figures with which Germany wrestled in the Weimar period, the book maintains the same numerical designations as were used then and as appeared on her banknotes. That is to say, when a milliard meant one thousand million, when a billion was still a million times a million, when the term billiard was coined to indicate a thousand times more, and a trillion was 1,000,000 cubed. To have converted these words to the more modern usage, when a billion boasts only nine noughts and a trillion a mere twelve, might, I fancy, have added to what a German minister of the 1920s justly called the delirium of milliards.

No more today than in 1975 is it suggested in this history that any advanced economy is threatened with inflation approaching such severity as in post-Imperial Germany. Yet, as we move into the second decade of the twenty-first century, the sobering lesson remains: the folly for any government to choose the soft option when a nations economy must be protected; or to shrink from inescapable measures until it is politically too late, too suicidal, to take them.

Money may no longer be physically printed and distributed in the voluminous quantities of 1923. However, quantitative easing, that modern euphemism for surreptitious deficit financing in an electronic era, can no less become an assault on monetary discipline. Whatever the reason for a countrys deficit - necessity or profligacy, unwillingness to tax or blindness to expenditure - it is beguiling to suppose that if the day of reckoning is postponed economic recovery will come in time to prevent higher unemployment or deeper recession. What if it does not? It is alarming that some respected bankers and economists today, in the US as in Britain, are still able to commend the printing press (in so many words!) as a fail-safe, a last resort. A countrys budget can indeed be balanced in that way, but at the cost, to whatever degree, of its citizens savings and pensions, their confidence and trust, their morals and their morale.

At any rate, it is not hard to contemplate a recurrence of the challenging post-oil shock conditions of the 1970s which inspired this book in the first place. Then there were rocketing prices and wages, strikes and closures, unemployment, helplessness and hopelessness. In 1975, US inflation stood at 8%; Britains was rising from 10 to 27% (and was still at 18% in 1981 when Margaret Thatcher and Geoffrey Howe brought in the painful disciplines that defeated it); Japans rose to 30%. Valid measures needed to restore equilibrium were fierce and long, and the scars of both disease and recovery were slow to heal.

Peoples trust in their currency is here a central theme. As it evaporates, they spend faster, the velocity of circulation increases, a little money does the work of much, prices take off, and more money is needed. The quantity theory of money found its finest object lesson in Germany after the First World War. Today, opinion divides about the diagnosis - deflation, or inflation, or both; and about the cure - the harsh contraction of the State, or neo-Keynesian relaxation and quantitative easing.

Among the causes of this kind of misfortune, ill-judged philanthropic social experiments and ill-funded wars should no doubt be included. Germany has been there, twice; and the Weimar Republics experience adequately explains that countrys continuing determination, in or out of the Euro-zone, never to return.

Prologue

When a nations money is no longer a source of security, and when inflation has become the concern of an entire people, it is natural to turn for information and guidance to the history of other societies who have already undergone this most tragic and upsetting of human experiences. Yet to survey the great array of literature of all kinds - economic, military, social, historic, political and biographical - which deals with the fortunes of the defeated Central Powers after the First World War is to discover one particular shortage. Either the economic analyses of the times (for reasons best known to economists who sometimes tend to think that inflations are deliberate acts of fiscal policy) have ignored the human element, to say nothing in the case of the Weimar Republic and of post-revolutionary Austria of the military and political elements; or the historical accounts, though of impressive erudition and insight, have overlooked - or at least much underestimated - inflation as one of the most powerful engines of the upheavals which they narrate.

The first-hand accounts and diaries, on the other hand, although of incalculable value in assessing inflation from the human aspect, have tended even in anthological form either to have had too narrow a field of vision - the battle seen from one shell-hole may look very different when seen from another - or to recall the financial extravaganza of 1923 in such a general way as to underplay the many years of misfortune of which it was both the climax and the herald.

The agony of inflation, however prolonged, is perhaps somewhat similar to acute pain - totally absorbing, demanding complete attention while it lasts; forgotten or ignorable when it has gone, whatever mental or physical scars it may leave behind. Some such explanation may apply to the strange way in which the remarkable episode of the Weimar inflation has been divorced - and vice versa - from so much contemporary incident. And yet, one would have thought, considering how persistent, extended and terrible that inflation was, and how baleful its consequences, no study of the period could be complete without continual reference to the one obsessive circumstance of the time.

The converse is also true: except at the narrowest level of economic treatise or personal reminiscence, how can a fair account of the German inflation be given outside the context of political subversion by Nationalists and by Communists, or the turmoil in the Army, or the quarrel with France, or the problem of war reparations, or the parallel hyperinflations in Austria and Hungary? How can one gauge the political significance of inflation, or judge the circumstances in which inflation in an industrialised democracy takes root and becomes uncontrollable, unless its course is charted side by side with the political events of the moment?

The Germany of 1923 was the Germany of Ludendorff as well as of Stinnes, of Havenstein as well as of Hitler. For all their different worlds, of the Army, of industry, of finance and of politics, these four grotesque figures stalking the German stage may equally be represented as the villains of the play: Ludendorff, the soulless, humourless, ex-Quartermaster-General, worshipper of Thor and Odin, rallying point and dupe of the forces of reaction; Stinnes, the plutocratic profiteer who owed allegiance only to Mammon; Havenstein, the mad banker whose one object was to swamp the country with banknotes; Hitler, the power-hungry demagogue whose every speech and action even then called forth all that was evil in human nature. In respect of Havenstein alone the description is of course unjust; but the fact that this highly-respected financial authority was sound in mind made no difference to the wreckage he wrought.