First published in 1993 in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

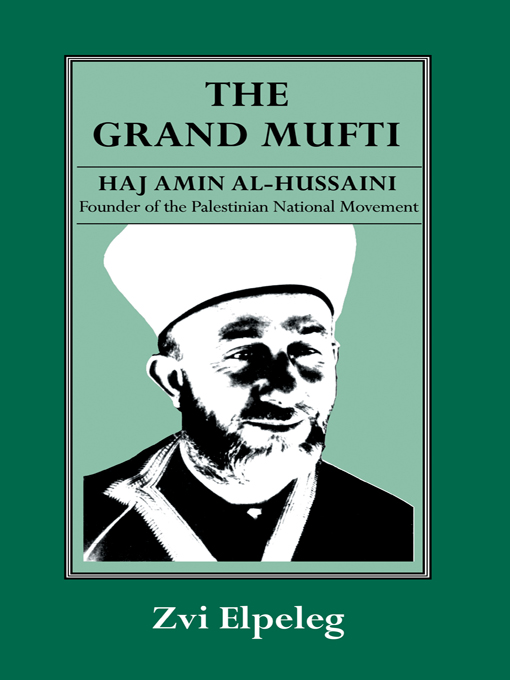

Copyright 1993 Zvi Elpeleg

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Elpeleg, Zvi

Grand Mufti: Haj Amin al-Hussaini, Founder of the Palestinian National Movement

I. Title II. Harvey, David III. Himelstein, Shmuel

956.9405092

ISBN 0 7146 3432 8 (Cased)

ISBN 0 7146 4100 6 (Paper)

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Elpeleg, Z. (Zvi)

[Mufti ha-gadol. English]

The grand mufti : Haj Amin al-Hussaini, founder of the Palestinian national movement / Zvi Elpeleg; translated from the Hebrew by David Harvey; edited by Shmuel Himelstein.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Husayni, Amin, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, 18931974. 2. Palestinian ArabsBiography. 3. PoliticiansPalestineBiography. 4. JewishArab relations1917 5. PalestineHistory19171948. I. Himelstein, Shmuel. II. Title.

DS125.3.H79E44131992

956.9404092dc20

[B]92-26148

CIP

This book was originally published in Hebrew by MOD Publishing House, Israel, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Routledge and Company Limited.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

Foreword

The rise of the Palestinian national movement after the First World War was a continuation of the pan-Arab national movement that had crystallised before and during the war. The common denominator of the two movements was the fact that both had arisen primarily as responses to external challenges.

The background to the emergence of the pan-Arab movement was the weakening of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century, and the tyrannical regime of Sultan Abd al-Hamid the Second in the last quarter of that century. Tension increased between the regime in Istanbul and groups of Arab intellectuals, primarily in Damascus and Beirut, after the Young Turks, who seized power in 1908, turned out to be zealous supporters of pan-Turkism, which they sought to impose on all the Empires ethnic groups.

Criticism of the regime took on an organised character during the last years of the nineteenth century, with the appearance of clandestine groups in Lebanon. and, eventually, in 1916, into the declaration of the Arab revolt by Sharif (later King) Husayn Ibn Ali.

It should be stressed that in the period preceding the First World War and during the war itself, only a few Arabs joined the nationalist movement. Religious considerations deterred Arabic-speaking Muslims from subversive action against the Muslim state, and these groups further viewed the association with the Muslim Sultans Christian enemies as a grave sin. Many others preferred to withhold their support from either side until it became clear who would win.

Representatives from the District of Palestine constituted part of the general national movement, and they participated in its various conferences, including the Arab Congress in Paris in June 1913. As in the general movement, so too in the Palestinian faction; the early activists were Christian intellectuals, particularly from Nablus and Acre. Unlike their colleagues from other countries, however, the Palestinian Arabs were concerned with the Jewish immigration to Palestine.

Long before the Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917), and many years before the outbreak of the First World War, the Palestinian Arabs faced the challenge posed by the Zionist movement, which itself greatly influenced the emergence of the Palestinian national movement. The increasing immigration of European Jews, who could now be seen in different parts of the country, the land purchase and the establishment of new settlements, all caused concern among the Palestinian political public. This concern, which was based partly on reality and partly on political propaganda, found expression in the Palestinian press published in the years preceding the First World War.

Arabic newspapers appeared in various parts of Palestine before the war, and expressed hostility to Zionism. They published exaggerated figures about the number of Jewish immigrants and land acquisitions. Especially anti-Zionist were al-Karmil (founded in Haifa in 1908), and Filastin (founded in Jaffa in 1911). The publishers of both these newspapers, and of a number of others, were Christians. In addition to distributing anti-Zionist propaganda, they took part in organising political and economic campaigns against the Jewish Yishuv.

During the course of the First World War, the nationalist political organisations made great efforts to enlist Palestinian Arabs from among the Arab towns of Palestine into an anti-Turkish front. None the less, the majority of the Palestinian public and its leaders were not swept away by the nationalist propaganda, and remained faithful to the idea of the integrity of the Empire. Moreover, even among those who wished to be liberated from the tyrannical regime, there were some who preferred to wait for the outcome of the war. In any case, during the war itself, there was very little opposition to Turkish rule. In contrast, the opposition to Zionism was widespread and encompassed all of the Palestinian political factions.

Toward the end of the war, reports began to reach Palestine of both the SykesPicot agreement and the Balfour Declaration. These reports greatly worried the Arab political and religious communities in Palestine. The Palestinian leaders launched a propaganda campaign in towns and villages, with the aim of arousing the masses to an anti-Zionist struggle. Within a short time, before the British had even completed the conquest of Palestine, nationalist organisations intended to fight Jewish immigration and land purchase had sprung up all over the country.