PITT LATIN AMERICAN SERIES

Catherine M. Conaghan, Editor

Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright 2020, University of Pittsburgh Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 13: 978-0-8229-4619-9

ISBN 10: 0-8229-4619-X

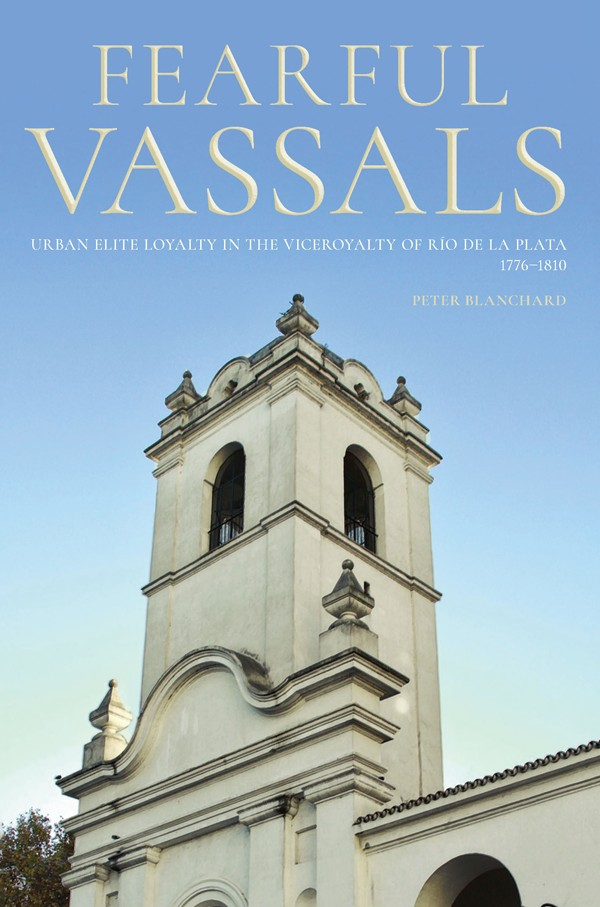

Cover art: El Cabildo de Buenos Aires

Cover design: Joel W. Coggins

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-8760-4 (electronic)

To Joanna

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As always, I owe an enormous debt to numerous people and institutions that have assisted me over the years as I slowly completed this book. First, I must thank the staffs of the various archives and libraries whose collections I have consulted. They include, in Buenos Aires, the Archivo General de la Nacin and the Biblioteca de la Academia de Historia; in Crdoba, the Archivo Arzobispal, the Archivo Histrico Municipal, the Archivo General e Histrico of the Universidad Nacional de Crdoba, the Biblioteca Mayor of the Universidad Nacional de Crdoba, and the Biblioteca Elma K. de Estrabou of the Universidad Nacional de Crdoba; in London, the National Archives; in Montevideo, the Archivo General de la Nacon and its Archivo Judicial, and the Museo Histrico Nacional, Casa de Juan Antonio Lavalleja; in Seville, the Archivo General de Indias and the Biblioteca de Estudios Hispano-Americanos; and in Toronto, the Robarts Library of the University of Toronto. My several research trips and conference presentations where I gave some of my preliminary findings were made possible through generous financial support provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the University of Toronto, and Victoria College of the University of Toronto.

Many colleagues and friends were extremely supportive, suggesting books and articles or supplying them, explaining esoterica or suggesting where explanations might be found, inviting me to present some of my semi-developed ideas at conferences and talks, and recommending or even providing accommodation in foreign cities. They include Alex Borucki, Roberto Brea, Vctor and Clara Cordn, Ed and the late Ileana Early, Marcela Echeverri, Erika Edwards, Ana Frega, Allan Greer, Lyman Johnson, Tony McFarlane and Angela OBoyle, Seth Meisel, Karen Racine, Rosa Sarabia, David Sheinin, Caroline and Godfrey Thomas, and Miguel Torrens. There are undoubtedly others and I apologize for failing to list them. Celia Braves put together the map that appears in the book. None of the above, of course, is responsible for any mistakes of fact or interpretation that appear in the following pages. All of the translations from Spanish that appear in the text are mine.

I cannot end without mentioning John Lynch whose influence is very much evident in the pages that follow but who sadly died before I completed the book. He did have an early version of the introduction read to him but this was shortly before his death and I have no idea of his reaction. I am certain that he would not have agreed with at least some of what I have written since it challenges arguments he made in his own work. Nevertheless, he was always tremendously supportive, especially in this case since what I was examining involved the part of Latin America and the period that first made his name known to students of the regions history.

Finally, my biggest debts are as always to Joanna and Adam. They have kept me focused on what is really important in life as I headed off on research trips and then struggled over every word and comma as I tried to make sense of the information I had collected. Adams contribution included expanding my knowledge and appreciation of wines from around the world and spending a memorable week with Joanna and me in Buenos Aires. Joanna joined me on a number of my visits, deepening her appreciation of Latin America and Spain. She read the entire manuscript twice, raising questions about content and suggesting grammatical and stylistic changes, in the process preventing many embarrassing errors. The two of them must be relieved that another fascinating yet all-consuming sector of the Latin American population has finally taken up residence elsewhere.

INTRODUCTION

On 25 May 1810 the elites of Buenos Aires with the vociferous backing of the citys lower classes made the fateful decision to remove the Spanish viceroy and assume direction of the viceroyalty of Ro de la Plata. The May Revolution, as it came to be known, marked a crucial step in the move toward self-rule and independence for what is today Argentina and the other countries that comprised the viceroyalty. Outside Buenos Aires the response to the events was mixed, with governing groups in some cases choosing to follow the Buenos Aires example and even accept its leadership. Others decided to pursue their own path, which for some meant remaining loyal to the crownat least for the time being. Fundamental to these decisions were the events in Spain that had left the country prostrate: the French invasion, the forced abdications in 1808 of the Spanish monarchs Carlos IV and Fernando VII, and their replacement on the throne by Napoleon Bonapartes brother Joseph. The developments created a political vacuum that provided an opportunity for separatists and supporters of independence in the colonies to promote their agenda of self-rule. They initiated a process that would ultimately break the bonds of loyalty that had existed between Spains king and his American vassals since the time of the conquest some three hundred years before.

In this work I examine those bonds in the viceroyalty of Ro de la Plata in the years between 1777 when the viceroyalty was created and the May Revolution of 1810, focusing on the elites of three of the viceroyaltys principal cities, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, and Crdoba. Urban centers throughout the colonial period were pivotal to Spanish rule in the Americas. They were the local administrative units that had jurisdiction over a wide swath of the surrounding countryside as well as being home to the bureaucrats, religious personnel, military men, merchants, artisans, workers, and members of other sectors of society who supported and participated in the various activities that constituted urban life and maintained Spanish rule. The cities were linked through ties to the king, religion, and the commercial activities that developed over the years. creation of the viceroyalty. Indeed, as shown in the following pages, those divisions, challenges, and uncertainties were an important factor in explaining their continuing loyalty.

Detailing elite loyalty was not my original aim in delving into the history of the viceroyalty of Ro de la Plata. Rather, my interest had been quite the reverse: to uncover the dissent and dissatisfaction that may have existed at the time in an attempt to clarify who were aggrieved and thus likely to join the dissidents calling for self-rule and independence in the early nineteenth century. The existence of such dissent had been evident in the colonies for some time. In the mid-eighteenth century the Spanish scientists Jorge Juan y Santacilia and Antonio de Ulloa noted the divisions that existed between Spaniards and American-born creoles in the parts of Spanish America they visited. The Prussian naturalist and traveler, Alexander von Humboldt, in his visit to the region between 1799 and 1804 found even deeper divides. He described the animosity that existed between Spaniards and creoles, with the latter increasingly calling themselves Americans as they objected to the denigration they faced at the hands of the Spaniards.