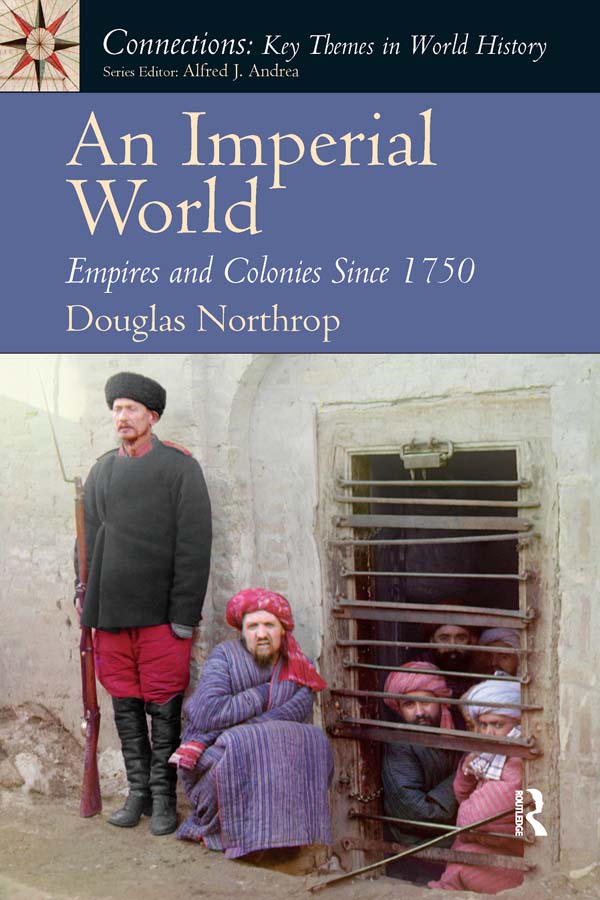

AN IMPERIAL WORLD

Empires and Colonies Since 1750

Douglas Northrop

University of Michigan

First published 2000 by Pearson Education, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2013 Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Cover Designer: Suzanne Duda

ISBN-13: 978-0-13-191658-6 (pbk)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Northrop, Douglas Taylor.

An imperial world: empires and colonies since 1750 / Douglas Northrop.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-13-191658-6

1. ColoniesHistory. 2. ImperialismHistory. 3. ColoniesHistory

Sources. 4. ImperialismHistorySources. 5. World history.

6. World politics. I. Title.

JV61.N67 2013

325.3dc23

2012017707

Contents

Connections: Key Themes in World History focuses on specific issues of world historical significance from antiquity to the present, employing a combination of elements: an introduction that places the theme into a broad historical context; four case-study chapters that combine to illustrate the dynamics of the theme across a wide range of cultures; four primary sources appended to each chapter that challenge the reader to probe more deeply into the issue at hand; images, maps, and, where appropriate, charts that illuminate each case study; and an epilogue (Making Connections), which contains both a summary analysis and, more important, further points for the reader to ponder. All of these features are presented in a reader-friendly manner.

The increasingly rapid pace and specialization of historical inquiry has created an ever-widening gap between professional publications and general surveys, especially surveys of world history. The purpose of Connections is to bridge that gap by placing the latest research and debates on selected topics of global historical significance, as well as some of the evidence upon which historians base their insights, into a form and context that is comprehensible to students and general readers alike.

Two pedagogical principles infuse this series. First, students master world history most easily if allowed to focus on specific themes and issues. Such themes, by their very specificity, as well as because of their general application, enable students to perceive and understand the overall patterns and meaning of our shared global past more clearly than is possible through reading, by itself, a massive world history textbook. Second, students learn best when asked to think critically about what they are studying. So far as the study of history is concerned, critical thinking necessarily involves analysis of primary sources.

To that end, we offer a series of brief, tightly focused books that embrace a radical simplicity and a provocative format. Each book goes to the heart of a key theme, phenomenon, or issue in world historysomething that has connected humans across cultures, continents, and time spans. By actively engaging with this material, the reader comes to understand in a nuanced and meaningful manner how often distantly located human cultures have been connected to one another as key actors in the epic story of world history.

Alfred J. Andrea

Series Editor

The 2010 Football World Cup held in South Africa and sponsored by the Fdration Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) has come and gone, having enthralled a global viewing public that is estimated to have been in excess of one billion persons. As 11 July approached, the day on which Spain would meet the Netherlands in the championship match, newspapers were reporting a curious phenomenon: large numbers of black South Africans were cheering for the Netherlands, and Latin American fans appeared to be solidly behind Spain. When Spain prevailed by a score of 10, Mexico City and Little Havana in Miami went wild with delirium. Wait a minute! Was not the Netherlands the home country that sent tens of thousands of colonists to South Africa, colonists who became Afrikaners? Had not an Afrikaner minority imposed a state-mandated system of oppressive apartheid on black South Africans for almost a half century from 1948 to 1994? Had not the Afrikaner government also stripped black Africans of their citizenship in 1958? Why cheer for the mother country of oppression? And why were so many Latin Americans fervently hoping for a Spanish victory? Most of mainland Latin America, from Mexico to Cape Horn (the major exception being Brazil), was subject to repressive Spanish colonial rule for roughly three centuries, and independence for most of Latin America was achieved in the early nineteenth century only after several bloody revolutions. Cuba was an even more extreme example of Spanish dominance. Claimed and held by Spain from 1492 to 1898, it finally achieved at least nominal independence in 1898, the result of a Cuban insurrection coupled with armed (and colonial-driven) intervention by the United States that Secretary of State John Hay characterized as a splendid little war. Why all of the cheering for former colonizers, especially colonizers who had been overthrown in reaction to their oppressive policies?

Douglas Northrop provides an answer in this splendid little book. As he notes, although many former colonies formed their national identities in the crucible of their fierce anticolonial struggles, once free, many of these former colonies found themselves still tied by history, blood, culture, and language to their former colonizers. This is certainly the case for most of Latin America, where language, religion, and overall culture carry the stamp (or footprints, to use Northrops term) of Mother Spain. The colonial past is long past, but these cultural artifacts, which form such an important part of Latin American identity, remain. Hence the cry Vamos Espaa! (Go, Spain!) echoed throughout Latin America and in US cities with large Hispanic-American populations.

The South African support of and affection for the Netherlands team also had its ties to the colonial past, strange as it might initially seem. Despite its historic and genetic ties with the Afrikaners, the modern Netherlands had been in the forefront of the global condemnation of apartheid. Beyond that, its team is multiracial, reflecting the Netherlands long history of colonial activity in Asia and the Caribbean. To name but three, Eljero Elia and Edson Braafheid are both of Surinamese descent, and Giovanni van Bronkhorst has a Moluccan mother.

Indeed, as already suggested, colonialisms vestiges are with us today, even in sport. I am often reminded of that when I see cricket players from India (where it is a national passion and a rite of passage for young men), Pakistan, Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere across the globe playing this game that defies my understanding on the verdant pastures of Central Park in Manhattan. And the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century US interventions in the Caribbean become all the more real for me when Big Papi, David Ortiz, is at the bat for my beloved Red Sox. Despite all of its negative consequences, the occupation of the Dominican Republic by US Marines from 1916 to 1924 resulted, generations later, in some of the finest baseball players on Earth now playing in the major leagues. And how can we ever forget Roberto Clemente of Puerto Rico?