First published by

Sidgwick and Jackson Ltd. in 1947

Second Edition published by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

First Edition 1947

Second Edition 1964

ISBN 0 7146 1669 9 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

Preface to the 1964 edition

EXCEPT for corrections to the text and the addition of a short new preface this book has been left unaltered. Any value it has is in the specific picture it offers of life as it appeared to be lived in an Igbo village at a particular stage of its history.

It is twenty six years since I lived in Umueke. Eighteen months ago, when I was staying in Umuahia, I paid it a flying visit of an hourall that was practicable at the time. Many of my friends had died but I found the one I was specially looking for, and his wife. I had been told that progress everywhere was such that I should not know the place. And so far as the big towns and the main roads are concerned much material improvement has taken place. But in the rural areas one wondered. No doubt progress is bound to be uneven, but one hopes, as many of my African friends hope, that it is not making the rich richer and the poor poorer. The people of Umueke crowded round me and my companion and urged us to help them with their agriculture or by coming and starting up a business of some kind among them. On the spot the significance of this was impossible to assess. But there was no mistaking the problem of unemployment in Eastern Nigeria, especially among the young people. Nor was there any doubt about the need to increase the production of home grown food. It is good to know that the present Prime Minister of Eastern Nigeria stresses the importance of agriculture.

If it were possible, one day, to live again for a time in Umueke as an ordinary individual, and to supplement scientific detachment by personal involvement, the result might be illuminating. To be a social anthropologist in the field is a severe strain both on ones own humanity and on that of the people one is among. One can but be grateful for their tolerance.

There are one or two small points that need bringing up to date. The census of 1953-54 estimates the number of the Igbo people at nearly five million. No more recent figures are yet available. (See p. 3.)

So far as the osu people are concerned, it is now against the law in Eastern Nigeria to call anyone osu. (See p. 23.)

Cowries would rarely, if ever, be used as currency now. Their disappearance is a pointer to the rise in prices which has made currency of such low value obsolete. (See p. 41.)

As to the former prohibition on carrying arms of precision, I do not know what the present position is. (See p. 65.)

Appendix

The years that have passed since the appendix was written have confirmed the importance of recognizing the factor of temperament, not least in the writings of psychologists themselves. If Janet, Freud and Jung can be seen as speaking for their temperamental affinities, and the fourth type the deliberate simplifiers, as dealt with by Dr. M. Mackenzie, it should be possible to see more clearly what in their work is of general validity and what only for those of a temperament similar to their own. How little this point is generally recognized can be seen in the generalizations of many of the followers of Freud or Jung.

Further than this, much needs to be done in relating the study of temperament to that of social groups. The light already shed on the psychology of individuals needs to be turned, with due caution, on that of social groups, It should be possible to isolate, or at least to recognize, the temperamental factor which enters into all social situations, whether political, religious, economic or other, and which bedevils understanding so long as it is unrecognized. Few things could be more misleading than to look on all social problems as psychological. But it is equally misleading to mistake for a factor of some different kind what is really an unidentified factor of temperament.

In his books, Contrast Psychology (Allen and Unwin, London, 1953) and Psychological Depression (Churchill, London, 1963) Dr. Mackenzie has clarified this question and has also made an interesting approach to the subject of temperamental types and social groups.

Orthography

The Note on Orthography on p. xi has been left standing as it refers to the body of the book and is still relevant. But it must be stressed that since 1961 there has been an official orthography for Igbo, as the Eastern Nigerian Government accepted the excellent recommendations of the nw Committee on Orthography which met earlier that year. In the place of phonetic symbols, roman letters with diacritic marks are used, the vowel symbols now being i e a u o in place of i e a u o

, and n being used for the velar nasal consonant.

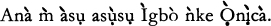

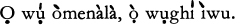

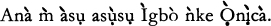

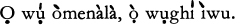

It has not been possible to transcribe the Igbo words or passages in the book owing to the photographic technique used in the new issue, but one or two transcribed examples are given here, with the type of tone marking used now in Igbo writings for foreigners or for linguistic purposes. The high tone is left unmarked, the grave accent is for the low tone and the vertical for the mid.

p. 6.

p. 17. onam

p. 61.

p. 99.

Throughout the book Ibo should be Igbo.

Map

The folding map at the end refers to Nigeria at the time of the writing of the book.

M. M. GREEN.

11 JULY 1963.

Preface

THIS book is based upon some of the material collected during two periods of field work, one of thirteen and the other of eleven months between 1934 and 1937 in South Eastern Nigeria. About six months of each tour were spent in the village here described and practically the whole cycle of the year from January to December was covered.

The writing of the book was in the first instance delayed by illness, the first draft being written in 1940-41 in the intervals of other work. Since then the first part has been more or less rewritten, also as pressure of other work allowed.

In view of administrative reorganisation in Ibo country which aimed at working more and more through indigenous institutions, and also because of the Aba Riots of the women in 1929-30, it was felt that more information about Ibo social organisation and particularly about the women was desirable. My colleague, Mrs. Leith-Ross, and I were therefore awarded Leverhulme Research Fellowships to enable us to study these questions. The area involved was so large that we did not work together, though we met at intervals for consultation.

, and n being used for the velar nasal consonant.

, and n being used for the velar nasal consonant.