Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2010 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior

University. All rights reserved.

This book has been published with the assistance of Rutgers University.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Caplan, Karen Deborah, 1970

Indigenous citizens : local liberalism in early national Oaxaca and Yucatn / Karen D. Caplan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

9780804772914

1. Indians of MexicoMexicoOaxaca (State)Government relations. 2. Indians of MexicoMexicoYucatn (State)Government relations. 3. LiberalismMexicoOaxaca (State)History19th century. 4. LiberalismMexicoYucatn (State)History19th century. 5. Local governmentMexicoOaxaca (State)History19th century. 6. Local governmentMexicoYucatn (State)History19th century. I. Title. F1219.1.O11C248 2009 323.11970727409034dc22

2009022700

Typeset by Thompson Type in 10.5/12 Bembo

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK WOULD have been impossible without the untiring and friendly aid of all those who work at the archives and libraries that I consulted in Mexico. Thank you in particular to, in Yucatn, Piedad Peniche Rivero, Candelaria Flota Garca, and Andrea Vergara Medina; and, in Oaxaca, Rosalba Montiel, Nemesio Martnez Galvn, and Blanca Sofa Moreno Cruz. Carlos Snchez Silva, who runs Oaxacas municipal archives, was particularly helpful in orienting me to research possibilities in that city. In Mrida, Othn Baos Ramrez did the same. Many people made my time in Mexico enjoyable as well as productiveespecially Sarah Buck, Cynthia Brock, Ray Craib, Todd and Kathline Hartch, Juliette Levy, Rick Lpez, and Jolie Olcott. Jacques and Renate Levy opened their home in Mexico City to me and helped me to get settled. And special thanks go to Mara Villegas Pedraza and Diana Torres Canto, who were the best of companions, and to their generous and welcoming families.

A number of organizations provided the funds and support that allowed me to research and write this book. At Princeton, the Graduate School, the Department of History, the Council on Regional Studies, the Program in Latin American Studies, and the University Center for Human Values were particularly generous. Thank you especially to Rosala Rivera, David Myrhe, David Figueroa-Ortiz, Kathy Baima, Melanie Bremer, Leah Kopscandy, and Audrey Mainzer. Thank you also to the members of the Princeton Center for Human Values graduate seminar, the Princeton Latin American History Workshop, the Princeton history departments Dissertation Writers Group, and the New York City Latin American History Workshop. John Coatsworth, David Freund, Peter Guardino, Dirk Hartog, Jennie Purnell, Richard Turits, and Francie Chassen-Lpez have all offered crucial readings and interventions. Peter in particular has been extremely generous with his own work on Oaxaca. Kenneth Mills has made an indelible mark on how I understand the people whom I write about and has provided inspiration in the creative and respectful way that he approaches both research and the profession itself. And I feel privileged to have worked with Jeremy Adelman, who has been an incredibly supportive adviser for this project from start to finish and whose suggestions are built into the fabric of this book. Thank you to all my colleagues at Rutgers University, especially Susan Carruthers, Prachi Deshpande, and Jan Lewis. Mark Hadzewycz provided able research assistance. To Christina Strasburger go profound thanks and respect for all the amazing things that she makes possible. My students over the yearsat Princeton, Rutgers, and the University of Marylandhave contributed to this work in both tangible and intangible ways. Many thanks to the folks at Stanford University Press, especially Norris Pope, Sarah Crane Newman, and Emily Smith, and to Margaret Pinette, for her excellent and indispensible copyediting.

And finally, there are many people whose contributions to my work and life are inseparable. In the academic world, Susan Carruthers, Meri Clark, Anastasia Curwood, Katie Holt, Sarah Igo, Lisa Purcell, and Nicole Sackley have all helped me to keep things in perspective. Liz Cook, Jason Frank, Kate Gordon, Daniel Handler, Nora Howley, Diana Linger, Courtney McCarthy, Gerard McCarthy, Elizabeth Meister, Kim Roberts, and Margot Sharapova contributed to this book in a less direct but no less important manner. Lorelei, Amelia, Owen, Rosalind, Isaac, Phineas, Alex, and Daria are small but inspiring. My familyArna, Martin, Bill, Rachel, Maggie, and Rosie Caplan and Elaine Freundare awesome. Thank you to Amtrak, to the garden, and to yarn. And thank you, lastly, to The BoysDavid, Jonah, and Benjamin, who are, simply, the best.

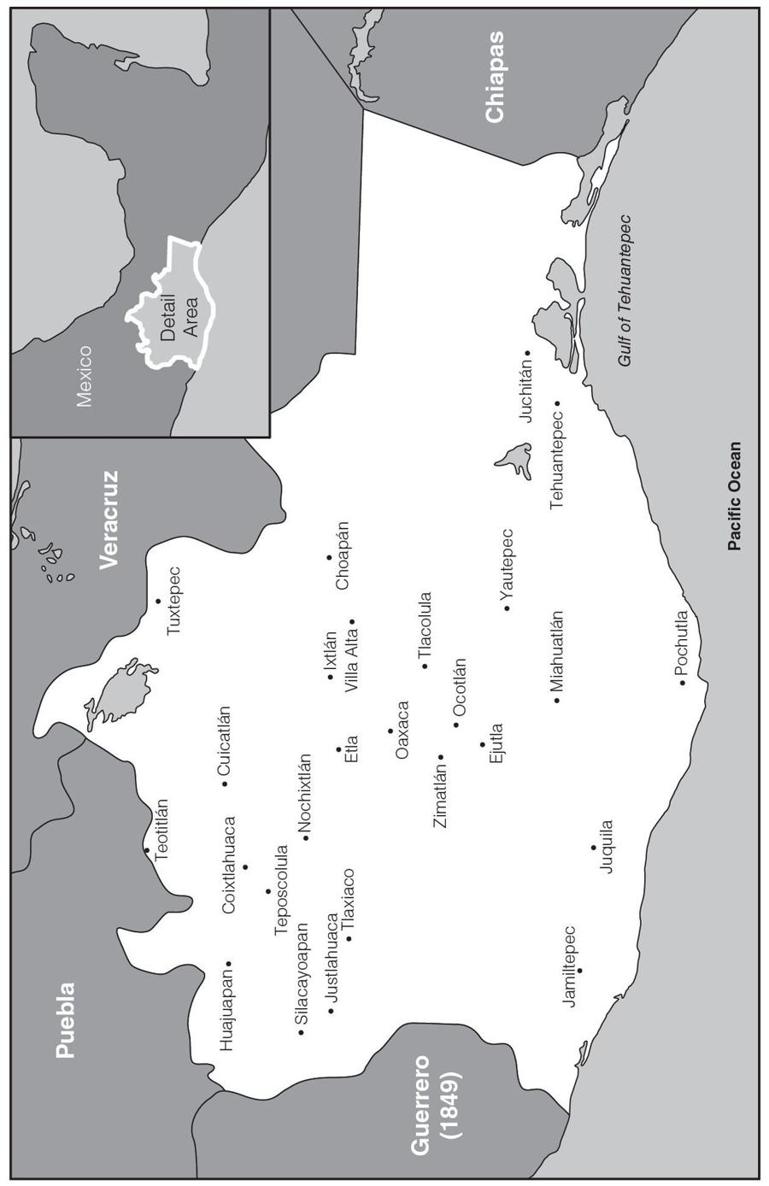

Figure 1.1 Oaxaca in the Nineteenth Century

The towns labeled here served as political and often economic centers. The vast majority of towns, however, cannot be respresented here. At independence , Oaxaca counted approximately 913 towns, a number that varied over the course of the era discussed in this book, but remained high.

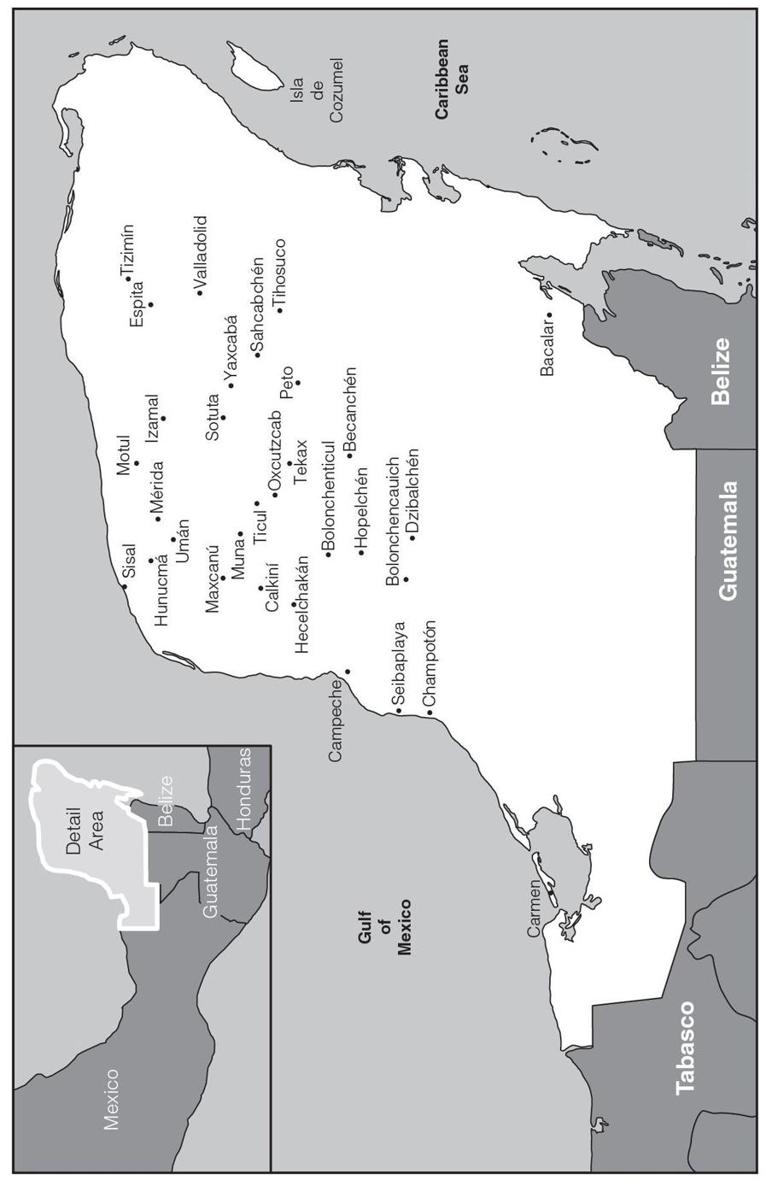

Figure 1.2 Yucatn in the Nineteenth Century

Yucatn, like Oaxaca counted far more towns than can be represented here. It is difficult to know with precision how many recognized towns existed at any given point. Some idea can be derived from Robert Patchs complications of towns in 1700 and 1716 (190) and between 1782 and 1791 (173, excluding the partidos of La Costa and Valladolid). See Robert W.Patch, Maya and Spaniard in Yucatn , 1648-1812 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), 254-263.

CHAPTER 1

National Liberalism, Local Liberalisms

IN APRIL 1846, A YUCATECAN OFFICIAL traveled through his jurisdiction, Motul, to inspect the villages and report on their condition to the state government. The picture the jefe poltico , or political chief, painted in his report was not favorable. Most striking was the near-universal neglect of public buildings. In town after town he saw that the casas consistoriales , buildings intended to house the municipal authorities elected under new republican rules, were near ruin. Jails and military barracks were ill maintained and thus inadequate for the enforcement of republican law. Schools worried the jefe as well. Many villages lacked them entirely, and where they did exist it was often impossible to find a qualified teacher, someone prepared to teach villagers the fundamentals of republican government. The jefe suggested that village authorities levy taxes to address some of these problems, but he recognized that in most cases there were simply no resources to tax. The jefes observations suggested that Mexicos new institutions were failing to transform the countrys indigenous people from colonial subjects into liberal citizens. There was often little distinction in the villages between the older indigenous government bodies sanctioned by colonial Spain and the new republican town councils established for independent Mexico. Because traditional indigenous scribes were often the only literate villagers, the jefe observed, they often served as perpetual mayors. Thirty-four years after the transition to liberalism, and twenty-five years after Mexicos separation from the Spanish monarchy and its establishment of a republican system, it appeared to officials across Mexico that in the villages little had changed.