It was Jimena Roses-Sierra who taught me how to write this book. Jimena supported this book long before it was conceived, and her critical eye has improved everything about it. Her unfailing faith, encouragement, love, and support in my pursuit of this project is inspiring. I would like to thank Pilar, Juan Ignacio, and Eduardo for their tremendous friendship, love, and support. I owe a debt of gratitude to my mother and father and brothers who showed me the value of hard work and education.

I would like to thank my colleagues and friends Edward G. Agran, Charlotte Fairlie, Elizabeth Haynes, Bonnie J. Erwin, Lisa Ottum, Daniel Kelly II, John Deignan, and Tammy Fraser who helped me settle in Wilmington. At Thomas More, Cari Garriga was the best office neighbor one could hope for and is an inspirational colleague and a wonderful friend. Jonathan Ablard has inspired me to become a better teacher, scholar, and a competent long-distance runner. I would like to thank Nancy Appelbaum, my advisor, for pushing me to think with my fingers and for supporting this project from its inception. I thank Dale Tomich, whose support and positivity helped motivate me to complete this project. Dales wide-ranging interests, from football to food systems, capitalism, and teaching, were inspirational and intellectually stimulating. Heather DeHaan always brought thought-provoking deconstructions to my material, and her efforts improved this book in innumerable ways. Gabi Kuenzli, whom I met in the Archivo de La Paz, has shared her insights and expertise. Gabis company and probing questions enhanced many of the ideas in this book. Ed Agran and Charlotte Fairlie welcomed me to Wilmington with open arms and provided a platform for me to succeed. Their dedication went beyond their duty.

I am especially grateful to the Provosts Office at Thomas More University, especially Cari Garriga, Elizabeth Hoh, and Kathleen Jagger for their generous support of this book throughout its development. This book would not be what it is were it not for my colleagues in the History and Political Science Department at Thomas More University, Patrick Egan, Ray Hebert, Jodie Mader, Jim McNutt, and J. T. Spence. I would like to thank the Binghamton University History Department, The Graduate School, and the Clifford D. Clark Diversity Fellowship, and the Tinker Foundation for supporting much of the research on which this book is based. Thomas More University Faculty Research Grants supported research for the manuscript in the final stages of writing. Kate Babbitts expert copyediting improved the book immensely. Maddie Holder and Abigail Lane at Bloomsbury Academic Press were generous and supportive and helped guide this book to publication. I would also like to thank the Anonymous Reviewers at Bloomsbury Academic Press. Their insights and suggestions have improved this book tremendously. The ATLAS writing group reminded me why I fell in love with history and it has allowed me to grow as writer, researcher, and scholar. Bonnie Erwins critical eye, enthusiasm, and deft touch were crucial to making this work what it is, and her ability to help me see the forest for the trees is much appreciated.

Many, many Bolivians and scholars of Bolivia also helped bring this book to fruition, including Pablo Choque, Claudia Riveros, Ivica Tadic, Rossana Barragn, Javier Marion, Juan de Dios Yapita, and Pilar Mendieta. The students and staff at the Archivo de La Paz were helpful, dedicated, and kind. The archivists at the Alcalda Municipal were always available to answer questions and offer advice when the research took me to unexpected places. The staff of the Cementerio Municipal de La Paz gave me space in which to work and access to the incredible materials in their archive. Scholars in the United States were also fantastic in their support: Brooke Larson, Laura Gotkowitz, Marisabel Villagomez, Tasha Kimball, Liz Shesko, and Matt Gildner were wonderful resources and generous scholars.

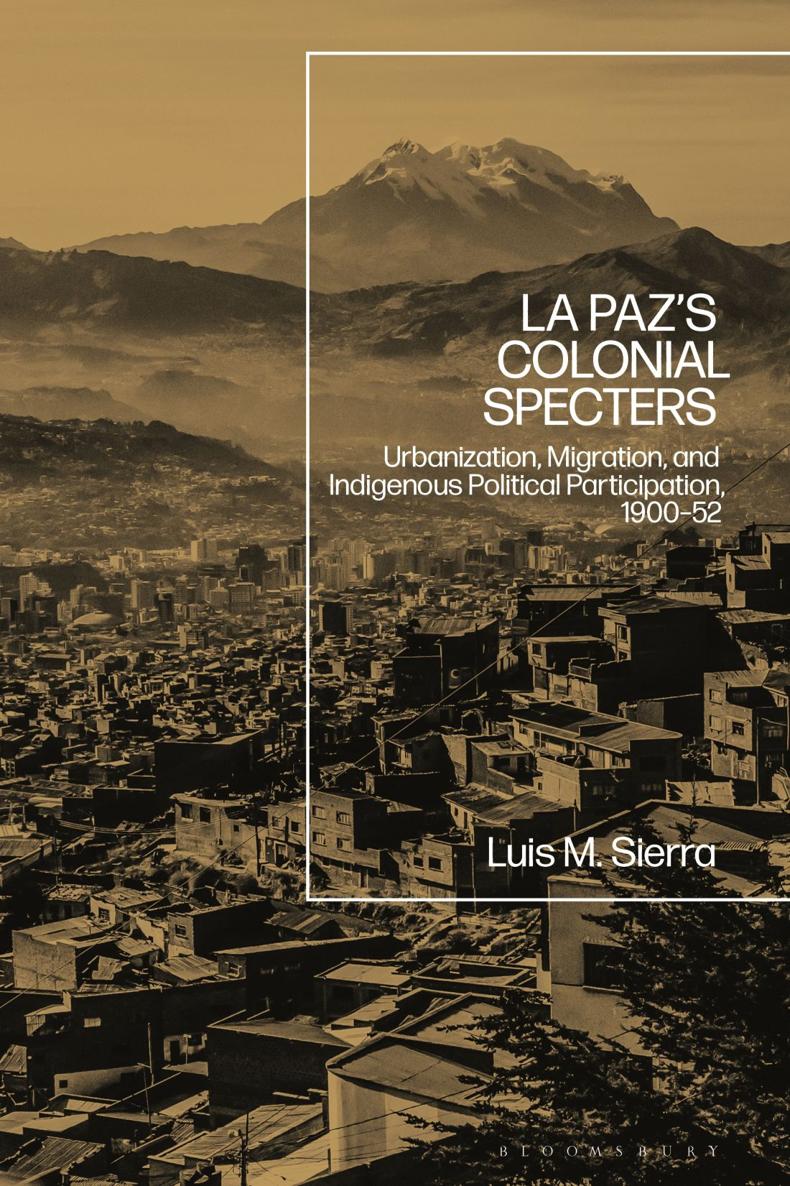

This book looks at the history of the city of La Paz, Bolivia, in the first half of the twentieth century from the perspective of its indigenous and working-class residents. These decades were a time of political upheaval for Bolivia. In the twentieth century, Bolivian society transitioned from a republic committed to nineteenth-century liberal values that tried to deprive the indigenous majority of political power and segregate them in the countryside to a republic that used the Bolivian identity as a unifying element. The transformations Bolivia underwent were fraught with conflict and instability. Sixteen presidents served from 1900 to 1952, most for very brief periods. The country underwent a military coup and a revolution; for a time the military was in power. The Great Depression of the 1930s hit Bolivia especially hard and made elites realize that an economy based solely on exports was no longer sustainable. Bolivia needed to modernize and its capital, La Paz, needed to look like other modern capitals. Bolivian elites were very sensitive about perceptions that their country was backward. They were especially concerned to avoid ridicule from people from the industrialized North.

For the elites who were on a mission to achieve modernity, indigenous people were undesirable. They dressed differently, they spoke different languages, and they brought rural ways and values into a city that elites hoped to make into a showplace. In the 1920s and 1930s, academics and politicians put forward racial theories that sought to justify policies that discriminated against indigenous people. In the 1920s, they succeeded in convincing the La Paz City council to pass regulations that sought to segregate indigenous people, even to make them invisible to the middle and upper classes. There was just one problem with these policies: elite Bolivians needed indigenous workers to cook their food, construct the new buildings of the beautiful city they envisioned, and produce their newspapers, among many other things. Thus began a subterranean dialogue between indigenous residents of La Paz and the elite and middle-class employers and politicians of the city. The overarching theme of this book is that the indigenous people won that debate. Throughout these decades, they made steady progress toward integration into the fabric of the nation, insisting consistently that as Bolivians they had rights to decent wages, electricity and water, schools in their neighborhoods, personhood through honorable behavior, and the right to build their neighborhoods as they wished.

The book touches on the economic, political, and social history of Bolivia in many places. Because the focus is on indigenous and working-class residents of the city, there is not always space to provide context for the broader historical themes in the individual chapters. At the same time, the book offers a corrective to the scholarship that has turned the Chaco War into the turning point in Bolivian twentieth-century history. Instead, I suggest that the Chaco War in some ways represented changes and, in others, continuity. What follows is a broad-brush sketch of some main themes in Bolivian history for the period from 1825 to 1952.