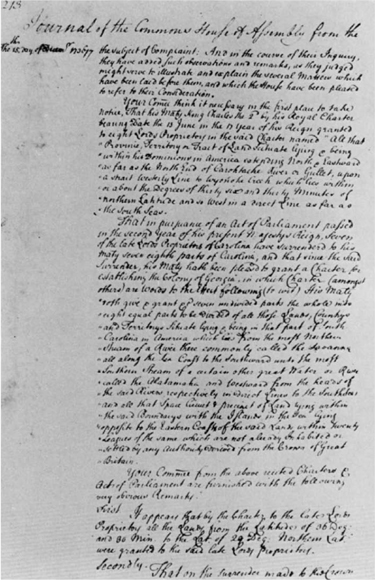

FRONTISPIECE: Page 213 of the Journal of the Commons House

of Assembly of South Carolina for December 15, 1737.

From The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly,

edited by James Harrold Easterby. Courtesy of the

South Carolina Department of Archives and History

Copyright 1970 by The University Press of Kentucky

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 7494066

ISBN: 978-0-81315232-5

The University Press of Kentucky is a statewide cooperative

scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College

of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Kentucky State

College, Morehead State University, Murray State University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western

Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506

Foreword

This study of the South Carolina legislative committee system is an attempt to illuminate the role of committees in the growth of colonial self-government. Partly because of frontier developments, the legislative committee became an institution which helped to solve many governmental problems of a New-World community. In a sense, the committees provided workshops for ideas that were to bring about legislative supremacy and, finally, independence.

Origins of the committee system can be traced, in part, to the parliamentary committees of medieval England. In 1670 Englishmen brought the committee system to South Carolina. Thereafter provincial legislative committees played a vital role in solving the problems of frontier economy and defense as well as in the emergence of self-government from 1719 to 1776.

One of the first steps toward greater home rule, the South Carolina revolution of 1719 against proprietary control, was largely a product of legislative and extralegal committee activity. In the decades of royal rule that followed, important developments occurred within the committee system. Among them was the elimination of royally appointed councilors from certain types of joint legislative committees. The dominance of joint committees by the Commons House of Assembly demonstrated that the colonists gradually increased control over their own affairs. Events on the frontier associated with Indian affairs and land development help explain this transition.

Expansion of the legislative committee system resulted in Commons House control of important governmental functions related to expenditure of money. Often these expenditures were made during periods of intercolonial and frontier warfare. Other types of committeescommissions, vestries, grand juries, and other boardswere used throughout South Carolina and had an important voice in local government. Most of the leading provincial South Carolinians became acquainted with problems of self-government in this frontier colony through experience on legislative or local government committees.

After 1761, when royal officials began to tighten their control over the colony, Commons House committees steadfastly opposed attempts to reduce their legislative power. The result of this struggle was a political deadlock which almost paralyzed constitutional government after 1769.

Powerful extralegal organizations controlled by executive committees appeared in the 1760s, both in Charles Town and on the frontier. These extralegal bodies rallied South Carolinians to their cause. Political leaders formed general committees that gave direction to the independence movement, and Commons members used their experience in leading home-rule forces. By 1775, a province-wide network of local extralegal committees augmented the General Committees power. The new Provincial Congress which was formed in 1775 relied upon a committee, the Council of Safety, as its executive body. South Carolina colonists had modified an Old-World parliamentary institution in a frontier environment to make it a vital part of their legislative program. Committees of the Provincial Congress helped bring about the colonys declaration of independence and first state constitution.

This study of South Carolinas legislative committee system thus illustrates the development of an institution which was vitally important in the growth of representative government in America.

A number of primary materials are of particular value in studying the politics and institutions of colonial South Carolina. The journals of the Commons House and those of the Upper House and the Council are excellent sources of information. The student of South Carolina history is fortunate to have the fine collection of the South Carolina Archives as well as the materials of the South Caroliniana Library of the University of South Carolina, the Charleston Library Society collections, and the resources of the South Carolina Historical Society in Charleston to assist him.

Although the number of additional public and private papers that have been published is not great, numerous materials from British archives have been copied and are now available at the South Carolina Archives Department in Columbia, and at the Library of Congress. A number of these sources are now duplicated on microfilm. In addition, selected volumes of the journals of both houses of the South Carolina General Assembly have been published, edited by Charles Lee, James H. Easterby, Alexander S. Salley, and others.

Some of the information drawn from these primary materials should be clarified. A major source of misunderstanding in colonial history is the existence of the Julian or Old Style calendar and the modern calendar. I have converted all Old Style dates into the modern dating system throughout the text. However, when authorities I cite use Old Style dates in primary sources, I have retained the Old Style dates in my notes.

A recently published study of South Carolina political history by the late M. Eugene Sirmans was particularly helpful to me in clarifying the political aspects of my subject. His book differs from mine in that his is a chronological investigation of politics before 1763. My study is basically an institutional treatment of the internal operations of the assembly and influential extralegal bodies with particular emphasis on the period following the French and Indian War.

This study grew out of research for my doctoral dissertation. I am indebted to my teachers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for their help in the preparation of this work, especially the members of my doctoral committee, Professors Henry M. Adams, A. Russell Buchanan, Rollin W. Quimby, and Robert Norris. In particular, I am grateful for the assistance of my adviser, Dr. Wilbur R. Jacobs, whose criticism and guidance have been invaluable.

Many other persons, too numerous to mention, have assisted me in my work. Of these, I would like to thank my classmates Professor David Kamens, Dr. Yasuhidi Kawashima, Professor Allan Rogers, Mr. Frank Bunker, Dr. Thomas Reeves, and Dr. Marvin Zahniser, who have given me excellent suggestions on this subject. I am also indebted to colleagues at Santa Barbara City College and the University of California, Santa Barbara, especially Mrs. Ruth Little, Mr. Donald Sawyer, Dr. Curtis Solberg, Mr. Raymond Loynd, Mr. Robert Easton, Miss Donna Page, Mrs. Donna Ellison, Mrs. Jeannette Dawson, and Mrs. Dorothy Annable. In addition I want to express my appreciation to Dr. Ruth Bourne for reading my manuscript.