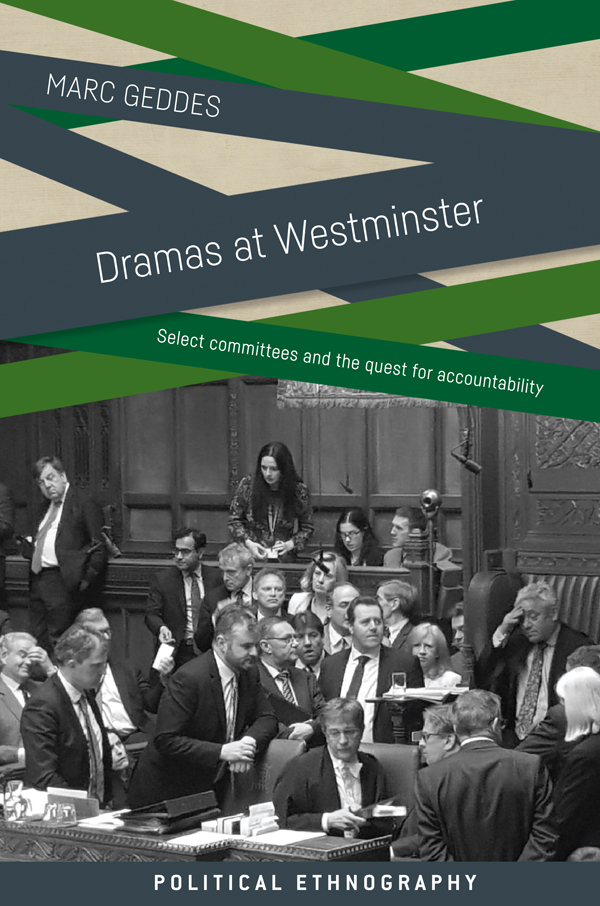

POLITICAL ETHNOGRAPHY

The Political Ethnography series is an outlet for ethnographic research into politics and administration and builds an interdisciplinary platform for a readership interested in qualitative research in this area. Such work cuts across traditional scholarly boundaries of political science, public administration, anthropology, social policy studies and development studies and facilitates a conversation across disciplines. It will provoke a re-thinking of how researchers can understand politics and administration.

Previously published titles

The absurdity of bureaucracy: How implementation worksNina Holm Vohnsen

Politics of waiting: Workfare, post-Soviet austerity and the ethics of freedomLiene Ozolia

Diplomacy and lobbying during Turkeys Europeanisation: The private life of politics Bilge Firat

Copyright Marc Geddes 2020

The right of Marc Geddes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 3680 0 hardback

First published 2020

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset by Newgen Publishing UK

Ethnography reaches the parts of politics that other methods cannot reach. It captures the lived experience of politics; the everyday life of political elites and street-level bureaucrats. It identifies what we fail to learn, and what we fail to understand, from other approaches. Specifically:

It is a source of data not available elsewhere.

It is often the only way to identify key individuals and core processes.

It identifies voices all too often ignored.

By disaggregating organisations, it leads to an understanding of the black box, or the internal processes of groups and organisations.

It recovers the beliefs and practices of actors.

It gets below and behind the surface of official accounts by providing texture, depth and nuance, so our stories have richness as well as context.

It lets interviewees explain the meaning of their actions, providing an authenticity that can only come from the main characters involved in the story.

It allows us to frame (and reframe, and reframe) research questions in a way that recognises our understandings about how things work around here evolve during the fieldwork.

It admits of surprises of moments of epiphany, serendipity and happenstance that can open new research agendas.

It helps us to see and analyse the symbolic, performative aspects of political action.

Despite this distinct and distinctive contribution, ethnographys potential is rarely realised in political science and related disciplines. It is considered an endangered species or at best a minority sport. This series seeks to promote the use of ethnography in political science, public administration and public policy.

The series has two key aims:

To establish an outlet for ethnographic research into politics, public administration and public policy.

To build an interdisciplinary platform for a readership interested in qualitative research into politics and administration. We expect such work to cut across the traditional scholarly boundaries of political science, public administration, anthropology, organisation studies, social policy, and development studies.

As a student, I found the lectures on Parliament a bore. As a lecturer, I taught UK Politics 101 and dreaded the reading for those lectures. Too many books and articles were worthy but unexciting. It was like wading through sticky mud. So, a little part of me picked up Marc Geddes manuscript on the UK House of Commons with trepidation. I sighed, put a Steven Wilson LP on the record deck, and settled in for an uninspiring couple of hours. I was so wrong. In my hands, I had the best book on the UK Parliament by a political scientist since Emma Crewes Lords of Parliament (Manchester University Press 2005), and she is an anthropologist.

Marc Geddes asks three questions:

How can we understand the everyday lives of parliamentary actors?

How do political actors interpret and perform their roles?

In what ways do everyday practices affect accountability in parliaments?

To answer these questions, he undertook participant and non-participant observation of the select committees of the House of Commons. He worked as a research assistant to a select committee in the House of Commons for 14 weeks during the second half of the 2010 Parliament (about 600 hours). He supplemented this work with negotiated access to observe the private meetings of other committees, and 100 hours of sessions available on www.parliamentlive.tv. He supplemented observation with 46 semi-structured interviews with select committee members (23), chairs (10) and staff (13). He facilitated a focus group with eight parliamentary officials. Finally, he drew on data such as official reports, briefings and statistics. It was an exercise in partial immersion that gave him many opportunities to immerse himself in the everyday life in the House.

There are two central arguments in this book. First, the study of Parliament does not have to remain mired in a descriptive institutional approach or preoccupied with prescribing reforms of the House. We can draw on other subfields of political science to refresh our approach. In this particular instance, Marc Geddes draws on interpretive theory and the methods of ethnography to provide such refreshment. He unpacks the individual beliefs, everyday practices, webs of belief or traditions, and dilemmas faced by parliamentarians.

Second, he uses metaphors from the theatre to explore how committee members perform. He is a wandering spotlight, or Super Trooper, beaming in on the several performing styles of members: specialists, lone wolves, constituency champions, party helpers, learners and absentees. Similarly, with the chairs, he finds they work with committee members or they act as chieftains, imposing their agenda on the committee. Committee hearings are theatre. The chair is the lead actor; the committee members are the supporting cast; the clerks act as stage directors; briefing papers are scripts; the public are the spectators; and committee rooms are the stage. In his phrase, MPs performances build a web of scrutiny.

In sum, focusing on the concepts of beliefs, practices, traditions and dilemmas offers novel ways of understanding parliamentary scrutiny. The core of this approach is telling our story about other peoples stories. We recover their stories to explain what they are doing and why. The dramas in the theatre of Parliament is Marc Geddes storyline for inscribing complex specificity in context, or writing a thick description. His book is a significant addition to the increasingly diverse literature of parliamentary studies.