Neil Joeck

Maintaining Nuclear Stability in South Asia

First published September 1997 by Oxford University Press for

The International Institute for Strategic Studies

23 Tavistock Street, London WC2E 7NQ

This reprint published by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

For the International Institute for Strategic Studies

Arundel House, 13-15 Arundel Street, Temple Place, London, WC2R 3DX

www.iiss.org

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

By Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

The International Institute for Strategic Studies 1997

Director John Chipman

Deputy Director Rose Gottemoeller

Editor Gerald Segal

Assistant Editor Matthew Foley

Design and Production Mark Taylor

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms and in other countries should be sent to the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

ISBN 0-19-829406-9

ISSN 0567-932X

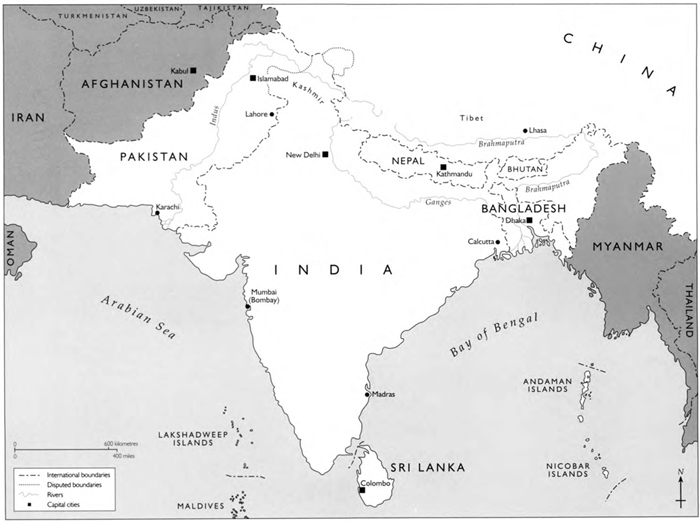

Map 1

South Asia

Map 2

Kashmir and the Line of Control

Map 3

Bangladesh

Map 4

The Sutlej River and the Indo-Pakistani Border

CSBM Confidence- and Security-Building Measure

CTBT Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

DAE Department of Atomic Energy (India)

DGMO Director-General of Military Operations

FMCC Fissile Material Cut-off Convention

GSQR General Staff Quality Review

HEU Highly Enriched Uranium

HUMINT Human Intelligence

IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency

IHE Insensitive High Explosive

IRBM Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile

NPT Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

NWFP North-west Frontier Province (Pakistan)

PAEC Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission

PAL Permissive Action Link

SIGINT Signals Intelligence

SRBM Short-Range Ballistic Missile

UNCIP UN Commission in India and Pakistan

Fifty years after their violent formation, India and Pakistan continue to face each other across a hostile and in places heavily armed border. Their conflict is marked by limited dialogue and intractable domestic and international disputes. Nuclear weapons now shadow their relations, and both sides may soon develop and deploy ballistic missiles.

Proponents of an explicit nuclear-weapon capability in South Asia argue that these conditions have made war unlikely given that both players' nuclear capabilities make a disabling first strike impossible.

Nuclear proponents maintain that, because past Indo-Pakistani conflicts were limited, future wars would in any case not involve the use of nuclear weapons. The two countries' three major wars were indeed limited in the sense that civilian and battlefield casualties were light, and the last two, in 1965 and 1971, were concluded within about two weeks. Internal strife in both countries, especially in Pakistan during the civil war preceding the creation of Bangladesh, has resulted in greater loss of life.

This paper takes a less optimistic view. It begins with two assumptions. First, India and Pakistan are unlikely to reverse their nuclear programmes in the next five to ten years. Both countries consider their national security to be threatened and believe that a nuclear capability is critical to the safety of the nation. Furthermore, they attained their nuclear status despite enormous outside pressure over two decades. This pressure, combined with sometimes exaggeratedly defiant internal rhetoric, has elevated the issue symbolically, making reversal politically hazardous.

The second assumption is that both sides may soon develop and deploy short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs). Although SRBMs may not be intended as nuclear-weapon delivery vehicles, both countries might assume that they could be configured to carry such weapons. This would dramatically change both sides' ability to manage escalation and to calculate behaviour in a crisis. The short flight times of SRBMs, the inability to recall them once launched and the requirement to delegate command compound those problems.

This paper argues that India and Pakistan's nuclear capabilities have not created strategic stability, do not reduce or eliminate factors that contributed to past conflicts, and therefore neither explain the absence of war over the past decade nor why war is currently unlikely. The influence of non-state actors (Kashmiri insurgents and unofficial government representatives), domestic disturbances (for example, in East Bengal and Punjab), and shortcomings in decision-making (concentration of power in the executive branch, limited intelligence) all contribute to instability.

The view that nuclear capability creates deterrence assumes that the shadow it casts makes conflicts less likely, more manageable, or even avoidable. However, this view ignores the important strategic and tactical implications of acquiring a nuclear capability. Far from creating stability, these basic nuclear capabilities have led to an incomplete sense of where security lies. Limited nuclear capabilities increase the potential costs of conflict, but do little to reduce the risk of it breaking out. Nuclear weapons may make decision-makers in New Delhi and Islamabad more cautious, but sources of conflict immune to the nuclear threat remain.

The development of command-and-control mechanisms would enhance stability in a crisis and improve the ability to avoid nuclear use in the event of war. Operational considerations nuclear doctrine, weapons' safety, alternative response options, intelligence and early warning would help to reinforce deterrence at ground level and ensure that both sides are not left with a choice between suicide and surrender.

A set of diplomatic steps must also be considered. In the absence of a defence against nuclear attack, bilateral confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) might reduce the likelihood of war and limit its consequences should war break out. Two dangerous but important areas needing attention are missile deployment and conventional force reductions. Agreements on issues such as trade, energy, military hotlines, security pledges and fissile-material control would not compromise security, but could capitalise on the positive diplomatic relations created in early 1997. It is time to think again about ways to reduce nuclear risks.