Preface

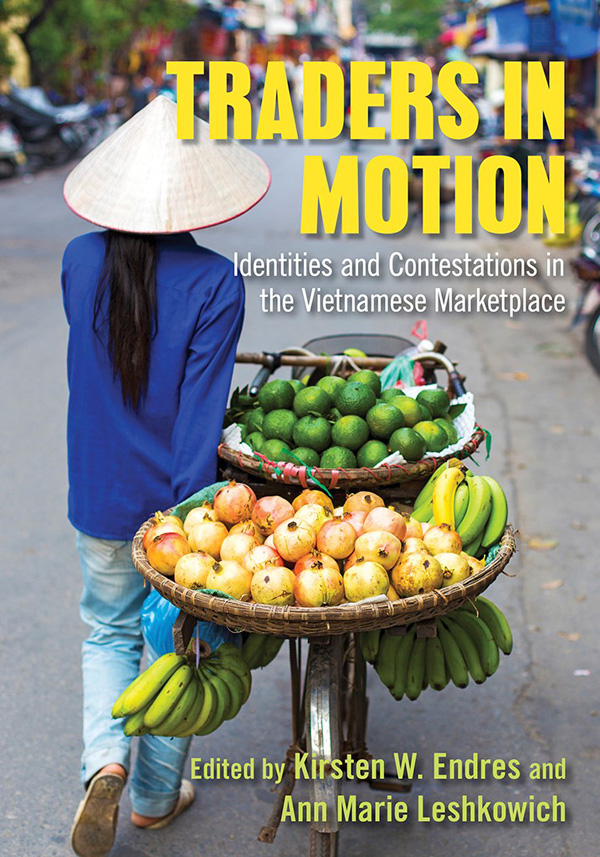

In Vietnam today, people are making markets, but markets are also making people. As anthropologists, we coeditors routinely seek to make sense of complex dynamics that extend across vast swaths of time and space by considering how they emerge in and through the lives of particular actors who are navigating particular spatial and temporal contexts. While international and national policies may seem to be the primary forces shaping the markets in which a street trader in Hanoi plies her wares, what those markets actually are, physically and conceptually, are every bit as much the product of her daily actions and the subjectivity that informs them. Trade and traders co-constitute each other.

The vibrancy of trade in market socialist Vietnam drew each of us independently to the study of marketplaces. Leshkowich began research in Ho Chi Minh Citys Bn Thnh market in the 1990s, where the opportunity and uncertainty posed by newly enacted market-oriented policies sparked struggles over class, property rights, social relationships, and memories of the past. These dynamics often centrally involved gender, as traders articulated identities as women that both worked to enhance their bottom lines and were personally meaningful ways of becoming proper, socially legitimate moral subjects in a palpably volatile economic and social environment (Leshkowich 2014a).

For Endres, markets moved to the center of attention when she joined the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in 2009. Her research group Traders, Markets, and the State in Vietnam, generously funded by the Max Planck Society and the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle/Saale, investigated market development policies as part of complex infrastructural planning assemblages aimed at national development, with a special focus on the entangled webs of social ties, state structures and discourses, and economic forces in which the lives of small-scale traders in market socialist Vietnam are situated. The groups researchers focused on local markets and other sites of small retail trade in different locations across contemporary Vietnam: the capital city, Hanoi (Lisa Barthelmes); a peri-urban village in the Red River Delta (Esther Horat); the northwestern uplands (Christine Bonnin); and two trading hubs on the Vietnam-China border (Kirsten Endres, Caroline Grillot).

In seeking to engage with the complexity of market making in a single country, Endress research group purposefully took a different approach from those of prior projects and edited volumes that have tended to focus on a particular aspect of trade, such as street trade, marketplaces, or a commodity type, in order to generate comparative case studies from different contexts around the world. Nonetheless, a comparative enterprise, albeit of a different kind, lies at the heart of the groups work and also inspires the present volume. Given the ongoing central role of nation-states or regions in shaping the legal and political environment for trade, it is analytically important to examine these dynamics, their impact on small-scale traders, and their uneven effects across time and space within one context. Doing so shows that markets evolve in unpredictable and uneven ways through uncertainty or, as we write in the introduction to this volume, through friction. Thus, while this volume certainly contributes to Vietnamese studies in an ethnographic and analytical sense, it has been explicitly designed to spark comparison by illuminating dynamics of spatialization, mobility, and borderwork that, we propose, shape trading contexts around the world.

To enable this comparative conversation, we have organized the volume into three thematic parts. These speak to each other, but they also can stand on their own. Each section has its own introduction that, along with the introduction to the volume as a whole, explicitly explores what Vietnamese trade, traders, and marketplacesin all their rich specificitymight reveal about trade, traders, and marketplaces beyond the borders of this particular nation-state.

The contributors to this volume first presented their chapters at the conference Traders in Motion: Networks, Identities, and Contestations in the Vietnamese Marketplace, hosted by the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in September 2014. The goal of this conference was to examine how Vietnamese small-scale traders experience, reflect upon, and negotiate current state policies and regulations that affect their lives and trading activities. By looking at various types and places of small-scale trade in contemporary Vietnam, the conference sought to shed light on local-level economic agency in the seemingly paradoxical context of Vietnams continuing socialist orientation, on the one hand, and contemporary neoliberal economic and social transformations, on the other. We here take the opportunity to extend our warm thanks to Chris Hann, director of the department Resilience and Transformation in Eurasia at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, for his enthusiastic support of this project. Special thanks go to Bettina Mann, Anke Meyer, and Berit Westwood for their excellent organizational and logistical work behind the scenes that enabled the conference to run smoothly. The event kicked off with a lively keynote lecture by Gracia Clark, who kindly agreed to provide the afterword to this book. We are particularly grateful to the team of discussants who supplied valuable food for thought: Regina Abrami, Chris Gregory, Gracia Clark, Erik Harms, Sarah Turner, and Vng Xun Tnh. Special thanks to Lale Yalin-Heckmann, Thomas Sikor, Oliver Tappe, and Roberta Zavoretti for chairing the sessions and sharing their views during the discussions. We also wish to thank Gita Rajan for language editing some of the chapters, Thi Thu Trang Nguyen for assisting in formatting and proofreading, and Jutta Turner for preparing the map.

At Cornell University Press, Sarah Grossman deserves special credit for her stewardship of this book from proposal to finished volume. We would also like to thank Karen Hwa for her work as production editor, Romaine Perin for copyediting, Fred Conner for his assistance with maps, illustrations, and other details of production, and Rachel Lyon for preparing the index. Our sincere gratitude extends to the anonymous reviewers of the book manuscript for their careful reading, insightful comments, and helpful suggestions. Finally, we editors would like to extend our appreciation to all of the volumes contributors for so enthusiastically embracing this collaborative enterprise. Scholarship, much like the trade that this volume chronicles, becomes all the more rewarding when it emerges through long-term relationships of exchange.

Introduction: Space, Mobility, Borders, and Trading Frictions

Ann Marie Leshkowich and Kirsten W. Endres

Marketplaces are fixed locations, but in Vietnam they are on the move, literally and figuratively. In Lo Cai, a northern upland city and provincial capital, a new, bigger market building is currently under construction. Building a new market means there will be even more traders competing for customers, one vendor muses. The new market will make things even more difficult for us. In Sa Pa, a popular tourist destination in the same province, traders are not happy with the local governments plan to relocate the towns bustling central market. While the government is trying to create economic opportunities, the traders dont see any opportunities in this relocation plan, a seller of medicinal herbs argues. Elsewhere in the northern uplands, some of the newly built or relocated marketplaces already lie fallow, the victim of high rents and out-of-the-way locations. Similar dynamics also plague Vietnams capital, Hanoi. Several old-style marketplaces have been turned into upscale shopping malls, with former vendors consigned to the basement. A trader in one of these markets reports that she has lost many of her former clients. She now has so much time on her hands that she can even prepare the family meals during her working hours at the market.