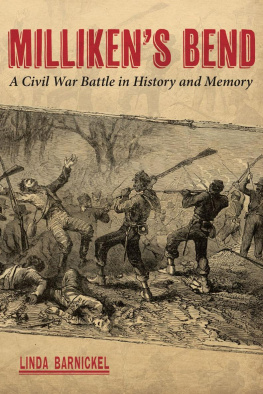

Winner of the Jules and Frances Landry Award for 2013

MILLIKENS BEND

A Civil War Battle in History and Memory

LINDA BARNICKEL

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

BATON ROUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2013 by Linda Barnickel

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

FIRST PRINTING

DESIGNER: Mandy McDonald Scallan

TYPEFACE: Whitman

PRINTER: McNaughton & Gunn, Inc

BINDER: Acme Bookbinding

All maps by Mary Lee Eggart

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barnickel, Linda A.

Millikens Bend : a Civil War battle in history and memory / Linda Barnickel.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8071-4992-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-4993-5 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-4994-2 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8071-4995-9 (mobi) 1. Millikens Bend, Battle of, La., 1863. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Participation, African American. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865African Americans. I. Title.

E475.4.B37 2013

973.7'415dc23

2012023811

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

For Corydon Heath, George Conn, Big Jack Jackson, and all the others like themofficers and enlisted men, white or black, who died on the altar of freedom.

It was a much more severe engagement, and more important in results, than was at first anticipated.

Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1863

The war for the Union, whether men so call it or not, is a war for Emancipation.

Frederick Douglass, Why Should a Colored Man Enlist?

CONTENTS

1. The Dark Pall of Barbarism

Emancipation as War Crime

2. Eternal Vigilance

The Insurrectionary Menace and Vigilante Response

3. All Is Uncertain

Civilians in Louisiana and Mississippi

4. The Triumph of a Noble Purpose

Emancipation Comes to Northeast Louisiana

5. I Cannot Tell How It Was I Escaped

The Bloody Battle at Millikens Bend

6. A Disagreeable Dilemma

The Fate of Union Prisoners, Black and White

7. This Battle Has Significance

Millikens Bend and the Wider War

8. We Intended to Fight for the Country

The Limits of Freedom, 18631865

9. A Terrible Aftermath of Injustice

Violence in the Postwar Era

ILLUSTRATIONS, MAPS, AND TABLES

Brig. Gen. Paul Octave Hbert, CSA

MAPS

Lynching Victims by Race, Northern Louisiana, 18781925

TABLES

PREFACE

The only certainty is overwhelming ambiguity, writes Tim OBrien in his Vietnam War classic, The Things They Carried. He could have been writing about Millikens Bend.

My journey began with misinformation. Taken prisoner and murdered by the rebels, July, 1862. So read the entry next to Corodon [Corydon] Heaths name on the Shober broadside, a copy of which was sent to me in late 1991 by my friend Paul Rambow. We both shared a deep interest in the history of Corydon Heaths original unit, Battery G, 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, and Paul had already been doing a considerable amount of research and correspondence (back in the days before the ubiquity of the Internet and e-mail revolutionized research). By the time I came along, he and many others affiliated with a reenactment group of the same name as Heaths unit had the basic history of the battery well sketched out. Paul even wrote an extensive and detailed history of the battery, which is now available online.

I left my copy of the broadside filed away for a year or so, referring to it occasionally as I researched other individuals and the battery as a whole. One day, as I looked at it more closely, I was drawn to the entry by Corydon Heaths name. Murdered. What an odd word to encounterit was wartime, after all. Taken prisoner and murdered by the rebels. Murdered after being taken prisoner? Whatever happened to bring about something like that? Was this just a bit of postwar bitterness and exaggeration? What had happened? I wanted to learn more.

Thus began my quest. I soon learned that Heath had died in 1863, not in 1862 as the broadside claimed. The Illinois adjutant generals report said Heath was promoted to captain in the 9th Louisiana Colored Infantry in April of 1863 and mentioned nothing about the circumstances of his death. Why then, did the broadside place his death a year earlier and call it murder? The beginnings of my search were representative of what I would find throughout my research. Time and again, one tiny particle of information would lead to anotherand create more questions. I spent hours in archives in Washington, DC, and throughout seven states. Research was often painfully slow. An entire day of work might result in only one or two useful bits of informationor none at all. Too often, the records were silent, confusing, or missing altogether. How fitting it was that my fascination with this case began with misinformation.

After obtaining Heaths military service records and the pension file for his children, the basic facts became clearer. Heath had indeed been taken prisoner and reportedly executed for serving as an officer in a regiment composed of recently liberated slaves. This knowledge led me directly to the fight at Millikens Bend, Louisiana, a nearly unknown action that took place on June 7, 1863 (not July 1862, when Shober placed Heaths death). I was surprised to discover that relatively little had been written about this small but very sharp fight on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Even books that concentrated on African American soldiers during the war gave it scant mention. No doubt overshadowed by the enormous clashes at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Millikens Bend seems to have vanished from history almost as soon as it occurred. Furthermore, the site of Millikens Bend was washed away by the mighty river decades ago. I found the fate of the physical battlefield and the nearby surroundings of the bayous of northeastern Louisiana to be a fitting metaphor for the events themselves, obscured long ago and today all but lost to history. Like trying to navigate through the tangled growth of a bayou, the forward movement and research involved in this project was laborious, painstaking, confusing, and difficult.

Millikens Bend was part of a trinity of battles in the summer of 1863 in which black troops under the Union banner played a prominent part. The engagements at Port Hudson, Louisiana, in late May, Millikens Bend in early June, and Fort Wagner, South Carolina, in Julyall coming in quick successiondid much to publicize the valor of black troops in battle.

Each battle had its own characteristics, and a brief comparison may be in order. At Port Hudson, the two black regiments of the First and Third Louisiana Native Guards were only a small part of a much larger operation. They had been in the United States Army since late 1862, having originally offered their services briefly to the Confederacy at the start of the war. Composed predominantly of free blacks and Creoles from New Orleans, these regiments initially drew their officers from the same population. By the time of Port Hudson, however, Gen. Nathaniel Banks forced the Third Regiments black officers to step down and replaced them with white men. The First Regiment had not yet been similarly reorganized. Both regiments served with honor and distinction at Port Hudson, especially in the trying assaults on May 27, earning praise from their peers and the press, despite bloody tactical blundering by their commanders.

BATON ROUGE

BATON ROUGE