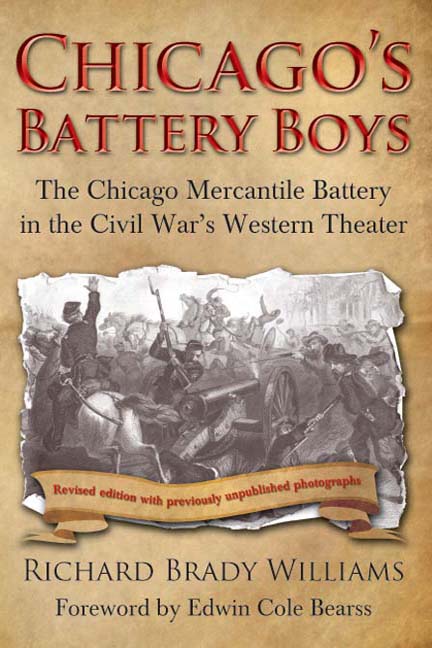

2005, 2007 by Richard Brady Williams

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-932714-38-8

eISBN: 978-1-61121-006-4

First paperback edition, first printing

Published by

Savas Beatie LLC

521 Fifth Avenue, Suite 3400

New York, NY 10175

Phone: 610-853-9131

Front cover: Death of Sergeant Dyer, engraved by J. J. Cade

Back cover: Chicago Mercantile Battery bugle, courtesy of Don Troiani

Cover design by Taylor J. Poole

Savas Beatie titles are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more details, please contact Special Sales, P.O. Box 4527, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762, or you may e-mail us at sales@savasbeatie.com, or click over and visit our website at www.savasbeatie.com for additional information.

To Mary Jo, my wife and best friend for 31 wonderful years, who has supported my passion for preserving American Civil War stories, memorabilia, and battlefields;

To my son Rick and daughter Elizabeth for their love and encouragement;

And in memory of my avid-reading parents, Charles Brady and Josephine Nancy Williams, who are not here to join me in celebrating the publication of Chicagos Battery Boys

Authors Note

I n preparing to edit the Chicagos Battery Boys diaries, letters, and memoirs, I studied dozens of first-hand Civil War accounts and discovered that there was no uniform way of approaching a project like mine. After considerable thought I decided to only lightly edit the letters and firsthand accounts that appear in this book. I believe this will make it easier for readers to enjoy them without getting bogged down trying to decipher run-on sentences, inconsistent punctuation, and so on. My approach has been, When in doubt, leave it alone.

I have preserved the original writingsincluding grammar, syntax, era-related misspellings, changes in tense, shifting points of view, etc., that are repeatedly wrong but reflect the writers idiosyncrasieswhile correcting blatant errors and adding consistency to punctuation and paragraph divisions. Hopefully this editorial process will make it easier for readers to move smoothly between my narrative and the eyewitness accounts. (Some of Will Browns personal discussions about his family, along with non-Civil War topics about Chicago and St. Joseph, have been excised.)

Any criticism about this editing strategy should be aimed at me and not my publisher.

Epilogue

A fter mustering out on July 10, 1865, the men in the Chicago Mercantile Battery headed for their respective homes. They were ambivalent about the wars end. Although thrilled to be reunited with their families and friends, the Battery Boys were also sad about having to say farewell to the comrades with whom they had camped, waged war, and shared their lives. The artillerists had traveled side by side on horseback, caissons, and limbers, riding along the dusty back roads of the Trans-Mississippi South. Together they had seen the elephant. And now it was all at an end.

Pat White returned to one of the shabby Irish neighborhoods in Chicago, broken in health because of the lingering effects of his thirteen-month ordeal at Camp Ford Prison. Friends may have noticed that his countenance was as dark as his complexion. His once-powerful six-foot frame was weakened now, his broad shoulders bowed by years of war. As fellow immigrants, his friends understood Whites lack of optimism about building a postwar career. Although the poor man captain had succeeded in leading a rich mans battery, White did not have the same civilian opportunities that were available to his well-educated soldiers like Will Brown, who were better equipped to take advantage of the ongoing Industrial Revolution. White returned to his deceased parents home to help his sister raise their siblings. There, he contemplated his future in Chicago as an unskilled laborer in a technologically advancing economy.

Restless and unsatisfied with his new life in Chicago, White moved to Albany, New York, where he met a widow named Annie Owens. They married on May 10, 1866. In November, he declined a commission as second lieutenant in the U.S. Armys 41st Infantry Regiment. The following year he became involved in a fish and oyster business. As the years passed the memories of his effective leadership on a variety of Civil War battlefields faded. The Irishman settled for a series of clerical jobs. He spent the last 20 years of his life working as a night watchman in the state controllers office.

Although White never earned much money, he somehow found the means and the time to travel extensively. He made the long, arduous train trip from Albany to Chicago to attend battery reunions for both Taylors Battery and the Chicago Mercantile Battery. He traveled twice to Vicksburg, where he helped place monuments and markers to highlight his batterys service during Grants siege. Another example of Whites hard work to preserve the accomplishments and sacrifices of soldiers during the war occurred around 1890, when the ex-captain spent two years lecturing at the Battle of Gettysburg panorama (one of the 360-degree Cyclorama paintings produced in 1883 by the French artist Paul Philopoteaux). Most likely he made his presentations at the exhibit in Chicago.

After he mustered out, Will Brown returned to St. Joseph, Michigan, to visit his father and older brother Henry. He had not seen either one since enlisting in the Mercantile Battery three years earlier. His younger brother Lib was still in Arkansas, where he was still serving as quartermaster in the 12th Michigan Infantry.

The elder Brown had been involved in the shipping trade for most of his adult life, having moved at the age of 30 from New York to Lake Michigan to manage a wholesale shipping business and construct boats used to navigate the St. Joseph River. He made the first trans-Lake Michigan shipment of wheat to Chicago. When the local economy plummeted, however, Hiram Brown was forced to move his family to Chicago, where he operated a line of boats on the Illinois & Michigan Canal. On returning to Michigan in 1862, the same year Will joined the Chicago Mercantile Battery, Hiram obtained a position as Deputy Collector of Customs for the port of St. Joseph. Henry followed in his fathers footsteps, working his way up from sailor, a job he took before the war at the age of 15. After recovering from his Resaca wounds, he became a captain in the Great Lakes shipping trade.

Like his father, Will started his business career in the wholesale commission field. He was intrigued with the process of reselling bulk goods, which arrived at Chicago on Lake Michigan vessels, to retailers throughout the Midwest. Shipping was in Wills blood, and he, too, would seek an opportunity to work in that field.

After returning from the war to Chicago, the hearty former quartermaster took a job as a bookkeeper for Arthur B. Meeker & Company. Working for this iron foundry, Will was able to learn about steelmaking, a new business destined to transform the United States into a global economic power. He learned his lessons well. Five years later Brown became Meekers partner. The pig iron the firm manufactured was essential in producing high-quality steel. Made in coal-heated furnaces, which smelted iron ore with coke and limestone, pig iron was at that time predominantly imported from Glasgow, Scotland. Arriving in New Orleans, the pig iron was transported on the same path the returning Mercantile Battery cannoneers had taken on their way back to Chicago after the war. From New Orleans, the pig iron was transferred to riverboats that hauled the raw material up the Mississippi River past Vicksburg and Memphis to Cairo, where it was transferred to railroad cars and taken to Chicago. To someone like Will Brown, who had learned logistics firsthand in the Civil War, this seemed to be sluggish and unprofitable. Ever resourceful, Will hired chemists whose subsequent experiments optimized the manufacture and shipment of pig iron from Great Lakes ore.