Books by Terrence J. Winschel

Triumph and Defeat:

The Vicksburg Campaign (1998)

Vicksburg:

Fall of the Confederate Gibraltar (1999)

The Civil War Diary of a Common Soldier:

William Wiley of the 77th Illinois Infantry (2001)

Vicksburg is the Key:

The Struggle for the Mississippi River (2003)

2006 by Terrence J. Winschel

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 1-932714-21-9

eISBN 9781611210187

05 04 03 02 01 5 4 3 2 1

First edition, first printing

Published by

Savas Beatie LLC

521 Fifth Avenue, Suite 3400

New York, NY 10175

Phone: 610-853-9131

Editorial Offices:

Savas Beatie LLC

P.O. Box 4527

El Dorado Hills, CA 95762

Phone: 916-941-6896

(E-mail) editorial@savasbeatie.com

Savas Beatie titles are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more details, please contact Special Sales, P.O. Box 4527, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762, or you may e-mail us at sales@savasbeatie.com, or visit our website at www.savasbeatie.com for additional information.

For Therese, my love;

Jennifer, our angel;

Bert, our pride; and Evan, our joy.

God has blessed me through you.

Preface

The 1998 release of Triumph & Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign, my first hard-bound volume, marked in many ways my coming of age as a historian. Although employed by the National Park Service since June 1977, my first eleven years with the agency were spent as an interpreter, during which period I held different job titles: park aide, park technician, and park ranger. My duties varied from title to title and from park to park (I worked in four different parks during this time frame: Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, Valley Forge, and Vicksburg), but mostly they consisted of manning the parks information desk, distributing brochures, and doing interpretive programs. It was not until 1988 that I moved into the ranks of the professional historians within the agency. Two men were largely responsible for my promotion: Bill Nichols, who then served as superintendent at Vicksburg National Military Park, and Edwin C. Bearss, who was at that time chief historian of the National Park Service. I shall ever be grateful to these men for their support, mentoring, and friendship that have molded my career and will always guide my stewardship of the national treasures entrusted to my care by the American people.

Life as a public historian is vastly different than the stereotype most people have of historians. Rather than spend my time with musty old books and documents doing research and writing, my days are devoted to public relations work, managing the cultural resources of the park (which are vast and complex), land acquisition initiatives, restoration projects, producing exhibits, doing interpretive programs, and an array of other fascinating and fun activities. (A visitor to my office upon seeing a hard hat and Swedish brush ax behind my desk asked, What are those things doing in here? to which I replied, Oh, thats standard equipment for a field historian.) But mostly, my time is consumed by the mind-numbing bureaucracy associated with the processes required in all Federal undertakings, processes such as GPRA, PMIS, NEPA, NHPA, and an endless stream of other acronyms that academic historians have never heard of, let alone the visitors who enjoy our national military parks and national battlefields. Yet, these time consuming and obscenely expensive processes have somehow become mission critical, and largely replace common sense and pragmatism in the management of our resources. For those of us in the field, these processes are the bane of our existence. (My friend and former boss at Fredericksburg, Bob Krick, told me upon his retirement that he no longer grinds corn for the Philistines. After almost thirty years of Federal service, how well I have come to appreciate that sentiment.) Although I look forward to the day when I too can stop grinding corn, there is much I still desire to achieve while working for the Philistines and will suffer through the bureaucratic nonsense for a few more years at least.

In order to promote my career and break into the historian ranks of the NPS, I have over the years had to sacrifice the very people for whom I was working so hard to providenamely my family. In addition to my work at the park, I attended night school for eight years and completed two graduate degrees, then taught night school for fifteen years to help put my wife through college and to provide for our childrens education. During this time I missed so many family momentswhich I shall always regret, but take consolation in knowing that my absence did produce some benefits for them that otherwise would not have been realized. This book, as with my previous works, is as much a credit to my family and their sacrifices as it is to my own efforts. Thus, it is fittingly and lovingly dedicated to them.

I also traveled extensively over the years speaking at Civil War Round Tables around the countryfurther sacrificing family time. (My wife, who is envious of my travels, frequently comments, You must see a lot of fascinating places, to which I reply, Mostly airports and hotels.) This is my favorite aspect of the job, dealing with people who share a similar interest in the Civil War and a passion for battlefield preservation. The friendships I have developed with many of you who read these pages are cherished. Please know that my gratitude and admiration are always yours, as are my heartfelt thanks for the wonderful work and accomplishments we have achieved together. (In fairness to my wife, I must confess that I have also seen some fascinating places in my travels.)

It is the dream of most historians to write a book, or at least get published in a journal or magazine. (Public historians are no different in this desire than our counterparts in academia.) Fortunately for me, there is more interest in the Civil War than any other aspect of world history, and thus better chances of getting published in one of the many fine magazines and journals devoted to the conflict that engulfed our nation from 1861-1865. My first magazine article appeared in 1980 and a steady stream of articles has followed ever since. Scores of articles (and many years) later, my dear friend and former coworker, Will Greene, encouraged me to finally write a book. (I always had a mental block when it came to writing books. Writing articles of 10-30 pages in length is one thing, but writing a book iswell, that is a much greater and far more difficult challenge.) Will, I can never thank you enough for encouraging me to reach my potential.

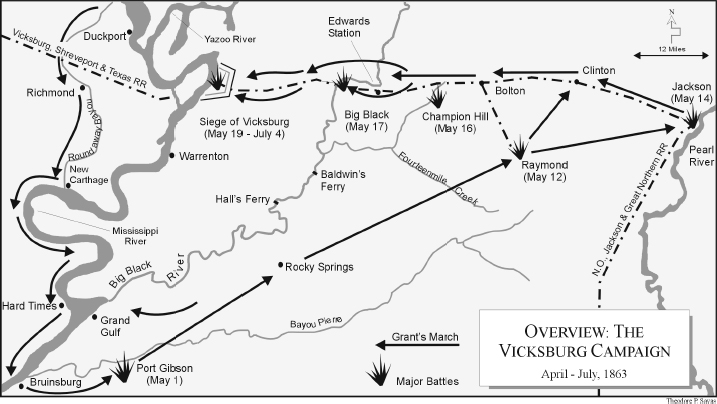

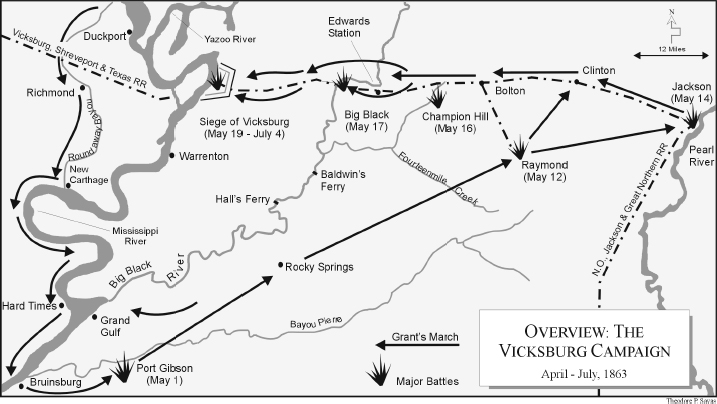

Surprisingly, Triumph & Defeat came about relatively easy for, rather than being a book-length narrative, it is a collection of academic-style essays that I produced on various aspects of the Vicksburg campaign. (Many of these essays were originally written as speeches to present on the Round Table circuit. Thus, the effort was more like writing a bunch of articles, yet resulted in the publication of a book.) It begins with an overview of the operations that focused on the Hill City, which laid the foundation on which the other essays then built. The essays that followed dealt with Grants march through Louisianathe opening stage of the campaign, Griersons Raid, the battle of Port Gibson, the battle of Champion Hill, and the May 19, 1863, assault against the Vicksburg defenses that highlighted the action of the Thirteenth United States Infantry. The essays continued with treatments of Union approach operations, the experience of Vicksburgs citizens under siege, the efforts of the Trans-Mississippi Confederates to rescue the city and its garrison, and the final days of the siege leading up to the surrender of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863.