Preface

I started researching and writing this book when the global victory of liberalism as the dominant rationality for organizing economic and political life seemed certain and ended it when it no longer does. For one of the main characters of the bookpostCold War political liberalismthe shifts have been significant. In 1991, when the Soviet Union crumbled, liberalism seemed to be the light at the end of history (Fukuyama 1989). As most people and institutions grappled to find their bearings, a wide variety of economic and political liberalization projects were rolled out across the former socialist world. Neither entirely imposed, nor fully locally generated, they were the product of specific histories, shifts in the global distribution of power, and renewed faith in the efficiency of the market and the value of individual freedoms.

In 2005, when I began fieldwork in Latvia on attempts to embed the liberal political virtue of tolerance in public institutions and the hearts and minds of the public, the Latvian version of post-Soviet capitalism had produced a dizzying credit-based economic bubble. The Latvian economy seemed to be going full speed ahead, and Latvias residents were urged to keep upput the pedal to the floor, as one politician put it at the time. The speed with which political liberalism was making its way into public institutions was much slower. This was often attributed to the difficulty of changing socialist mentalities. Moreover, Latvians did not want to give up their collective sense of self and insisted on the importance of history and the nation alongside individual liberties and respect for diversity. Nevertheless, there was little doubt among the proponents of political liberalism that things were moving in the right direction. After all, Latvia had just joined the European Union. Geopolitics and the law were on their side.

In 2017, as this book goes to print, the position of political liberalism in Europe is no longer so confident. The 200810 financial crisis stopped the pedal to the floor politics, resulting in severe austerity measures that expelled large numbers of Latvias residents from economic life and even from the country (Dzenovska 2018a, 2013b; Sassen 2014). This did not, however, weaken faith in the capitalist market, neither in Latvia nor globally. Neoliberalism, as Philip Mirowski (2011) has argued, has come out of the crisis stronger than ever. Instead, it is political liberalism that seems to be in crisis (Boyer 2016, Westbrook 2016).

Many scholars on the left link the crisis of political liberalism to the failure of liberal politics to address the grievances of those dispossessed by neoliberal forms of capitalism. As Ivan Krastev has put it, In order to prevent anticapitalist mobilization, liberals successfully excluded anticapitalist discourse, but in doing so they opened up space for political mobilization around symbolic and identity issues, thus creating the conditions for their own destruction. The priority given to building capitalism over building democracy is at the heart of the current rise of democratic illiberalism in Central and Eastern Europe (2007, 62).

Indeed, it is neoliberalism, rather than political liberalism, with its faith in the market as the most efficient and nonideological mechanism for resolving any disbalance in the system, that has come to be lodged in the hearts and minds of many ordinary people in Latvia and beyond (Mirowski 2011). Political liberalism has not taken such root. David Westbrook (2016) suggests that it may have served as an ideological layer that obscured the illiberalism at the foundation of the postWorld War II supranational political economy: as a house ideology of Western liberal democracies, it was a lingua franca or perhaps even a form of manners. It is the way civilized strangers address one another, the form of self-presentation that marks the better sort of people.

That said, both neoliberalism and liberalism are terms that should be used with care. Neoliberalism, as Sherry Ortner (2016) has recently pointed out, has become one of the dark forces in anthropological theory since the 1980s. As such, it often tends to be taken for granted as a foil against which to mount ones analytical and political interventions. Similarly, Lisa Hoffman, Monica DeHart, and Stephen Collier have argued that anthropology is concerned with neoliberalism, but that there are considerably fewer ethnographies of neoliberalism that deconstitute neoliberalism, that is, distinguish among, and focus attention upon, specific elements associated with neoliberalismpolicies, forms of enterprising subjectivity, economic or political-economic theories, norms of accountability, transparency and efficiency, and mechanisms of quantification or calculative choiceto examine the actual configurations in which they are found (2006, 10; see also Collier 2011).

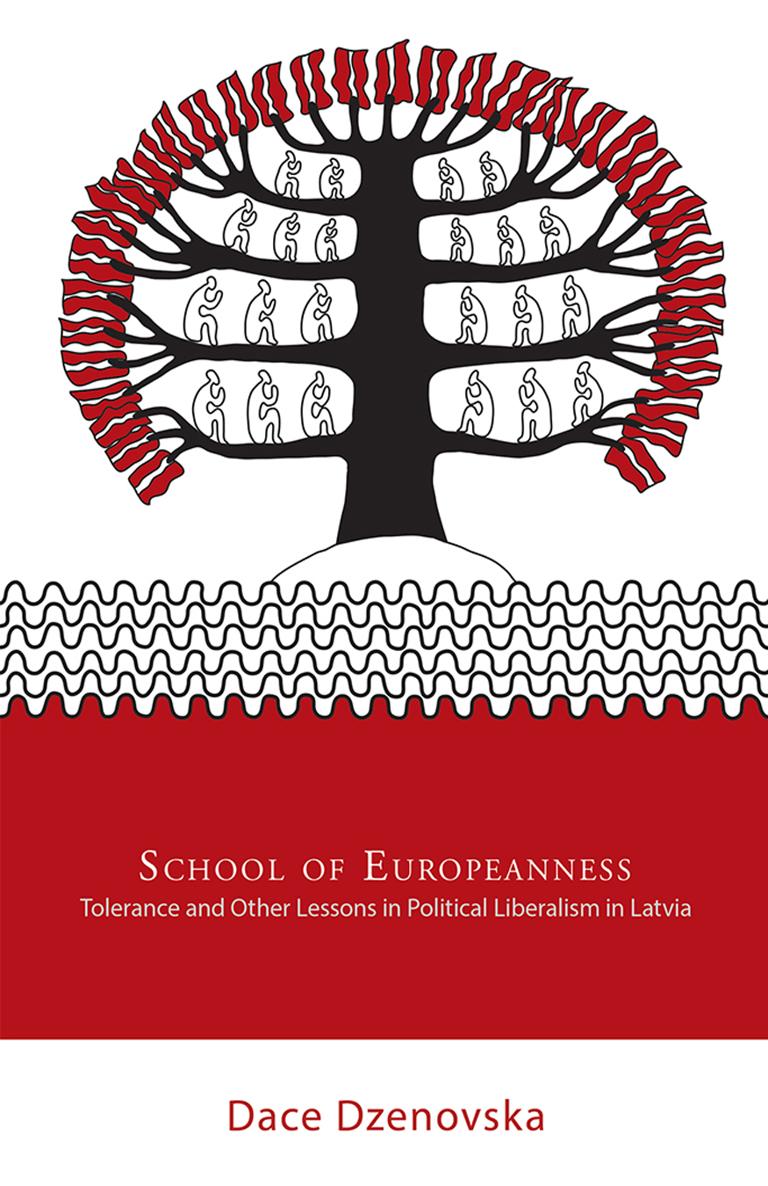

My book sets out to deconstitute political liberalism as an actually existing postCold War formation in Latvia. My primary focus is not on political liberalism as a coherent system of thought and action, but rather on the contested projects of remaking people and institutions in the name of political liberalism that emerged in the context of democratization initiatives that, in turn, were part of the postsocialist transition in Latvia. The configuration of elements that made up actually existing political liberalism in Latvia in the 2000s is both trans-locally recognizable and locally specific. On the one hand, these elements can be discerned in various European Union accession documents that travel across the European political landscape and emphasize the norms of human rights, minority rights, tolerance, civil liberties, and the rule of law. On the other hand, the contours of actually existing political liberalism in Latvia emerge through encounters and arguments, as these norms were being introduced and implemented. They appear as explicit policy measures, political discourses, and as tacit understandings, sensibilities, and dispositions of those who promoted them, as well as those who contested them. These constitutive elements of actually existing political liberalism emerge most vividly at times and in places where political liberalism is thought to be absentas, for example, in the context of the debates about Europes migration/refugee crisis, during which Eastern Europe was widely accused of lacking the sentiment and conduct of properly liberal Europeans (see the Introduction). It is such accusations of illiberalism that reveal the contours of political liberalism as an ideological and civilizing project located in historically specific fields of power.

I am not therefore suggesting that there is no need to think about how to talk with strangers or how to live with difference in Latvia and Eastern Europe more broadly. Rather, I am suggesting that in their confidence and moral superiority postsocialist liberalization projects may have missed the target. The confident adherents of postCold War political liberalism overlooked the role of geopolitics in the Latvian desire to join the free world, as well as misrecognized the significance of historical and cultural embeddedness by taking it to be an impediment rather than a resource. Many Latvians did not necessarily believe in the idea of Europe promoted by the proponents of political liberalism, but wished to join Europe and other international alliances, such as NATO, because they were not convinced that history had really ended. The perpetual threat of Russia loomed large in the Latvian national imaginary. Moreover, there were many Soviet-era Russian speakers in Latvia, and many Latvians were convinced that their loyalties were directed eastward.