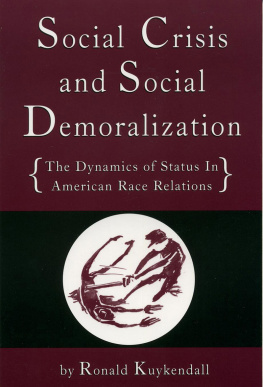

SOCIAL CRISIS AND SOCIAL DEMORALIZATION:

The Dynamics of Status in American Race Relations

Copyright 2005 by Ronald A. Kuykendall

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the author and publisher. For more information address:

Arissa Media Group

P.O. Box 6058

Portland, OR 97228

Tel: (503) 972-1143

http://www.arissamediagroup.com

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

First Edition, 2005.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2005922437

International Standard Book Number: 0-9742884-3-8

Cover design by Matthew Haggett

Edited by Ariana Huemer

Arissa Media Group, LLC was formed in 2003 to assist in building a revolutionary consciousness in the United States of America. For more information, bulk requests, catalogue listings, submission guidelines, or media inquiries please contact Arissa Media Group, LLC, P.O. Box 6058, Portland, OR 97228. Tel: (503) 972-1143.

Introduction

T he issue of race relations, that is, racial antagonism, racial antipathy, and racial inequality is a persistent problem within the United States. The race problem is disturbing because of the contradictory and conflicting ethical, moral, and irrational predicaments produced by situations of race relations. Several divergent explanations have arisen for the problem of race relations. These explanations disproportionately focus on African Americans and the deviant or pathological aspects of that group. Considerable attention has been given to a particular subpopulation of the African American citizenry described as the underclass: an unassimilated, socially and economically disadvantaged subculture with all the classic attributes of dysfunctionality. However, to speak of an underclass, although it may provide some objective reference to social position, is purely artificial and imaginary. The concept only makes sense to those conceiving of it. Such a class cannot be objectively differentiated, as it has neither members nor organization. What this term actually refers to is status: how others think of and treat individuals, as well as how those persons see themselves in the eyes of others. Consequently, behavior is towards persons and not towards class. Because the explanations are really attempts at explaining the dysfunctionality of individuals within the African American population, race becomes the significant variable.

The debate has frequently revolved around whether race relations are determined by race or by class with a racial bias. On the race side two different perspectives emerge: (1) the dysfunctionality within the African American population is an effect of inherent factors or traits that are deficient or abnormal; (2) the dysfunctionality within the African American population is an effect of racial antipathy, and hence prejudice and discrimination are the source of inequality and the resultant social and economic problems.

On the class side, the focus is on stratification within American society and within the African American population. The stratification is a consequence of economic factors that have dislocated or left behind a significant segment of the African American population, exacerbating dysfunctionality. The lack of socio-economic resources, rather than specific racial prejudice and discrimination, is the culprit that has caught this segment of the African American population unprepared to take advantage of economic changes.

The most widely held explanations about racial inequality and racial discrimination fall into three broad categories: deficiency theories, bias theories, and structural theories. This categorization is taken from the work of sociologist Mario Barrera (1979), and each will be considered here in turn.

Deficiency Theories

The contention of deficiency theories is that racial inequality and the concomitant social pathologies associated with African American behavior are located in either biological or cultural deficiencies. Therefore, the problem is an inherent inadequacy within African Americans.

Biological explanations, which assert that intellectual differences (read as intellectual deficiencies) are due to biological inheritance, have relied on IQ test scores. Although this category of explanation is held in scientific disrepute, it continues to stir considerable interest and even assert some degree influence (Gordon 1987; Hernstein 1971; Hernstein and Murray 1994; Jensen 1969, 1973; Wilson 1978).

Psychiatrist Frances Cress Welsing (1991) presents an inverse biological deficiency theory in which she asserts,

[T]he quality of whiteness is indeed a genetic inadequacy or a relative genetic deficiency state, based upon the genetic inability to produce skin pigments of melanin (which is responsible for all skin color). The vast majority of the worlds people are not so afflicted, which suggests that color is normal for human beings and color absence acts always as a genetic recessive to the dominant genetic factor of color-production. Color always annihilates (phenotypically and genetically speaking) the non-color, white. Black people possess the greatest color potential, with brown, red and yellow peoples possessing lesser quantities respectively (4).

In Welsings theory the psychological response of Europeans to their color inferiority is a defensive and uncontrollable hostility and aggression towards people of color. Combined with white demographic disadvantage, whites genetic inferiority leads to psychological defense mechanisms such as repression , reaction formation , projection , and displacement . Thus, racism and white supremacy are psychological responses, both conscious and subconscious, to this sense of genetic inadequacy faced by whites.

Cultural explanations locate racial inequality and African American social pathologies within abnormal or deviant cultural traits such as weak family structure, language handicaps, lack of work discipline, present rather than future orientations, dependency, and lack of success orientation. They emphasize cultural deficiencies as being responsible for the development of attitudes and values that limit opportunities or prevent escape from poverty. This tangle of pathology sets in motion a vicious circle resulting in drug addiction, crime, low educational achievement, and economic problems that reinforces the weak family structure and perpetuates abnormal and deviant cultural traits. Thus, it is not racism or genetics but African American cultural adaptations that are responsible for inequality and social pathologies (Auletta 1982; Banefield 1970; DSouza 1995; Moynihan 1965; Murray 1984).

Bias Theories

Bias theories focus on prejudice and discrimination as the source of inequality and the resultant social problems. Central to this analysis is the idea that discrimination is due to racial prejudice. Thus, racism stands out as the overriding factor responsible for not only inequality but also psychosocial problems that inhibit and thwart social and economic advancement (Bell 1992; Clark 1972; Grier and Cobb 1968; Hacker 1992; Myrdal 1944; West 1994).